When everything on Earth feels very strange and humans are up to all kinds of madness, it’s helpful to think about the larger universe.

There are things happening out there in the cosmos that have nothing to do with the human world. We are entirely incidental, irrelevant really. And that’s quite comforting.

The New Media Gallery’s show Indivisible takes this idea to new giddy heights. And I mean all the way to the furthest reaches of the galaxy.

The informing idea of the show is the invisible matter that bombards us humans, all day, every day. Stuff like muons. What the heck are muons? I’m glad you asked. Similar to electrons, albeit much heavier (some are 200 hundred times the mass), muons are particles created when cosmic rays bang into the Earth’s atmosphere. When they collide with earthly atoms at the speed of light, things get interesting.

True space travellers, muons are some of the only particles that make it to Earth. In South Korean artist Yunchul Kim’s installation Argos, they become art.

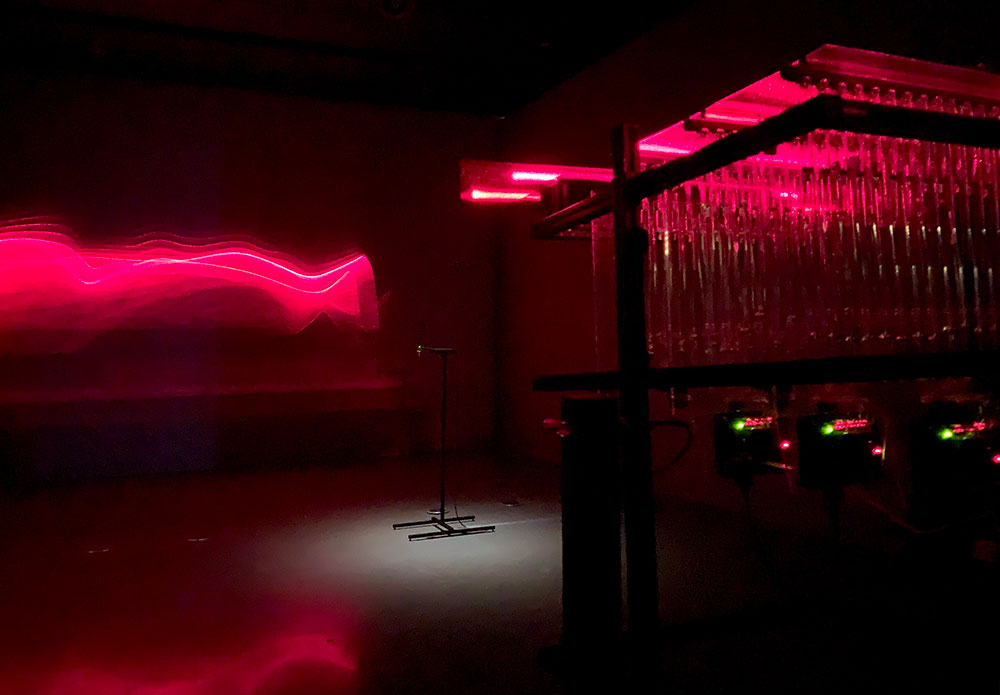

Composed of Geiger-Müller tubes, glass, aluminium and a micro controller, Argos looks a little like science fiction weaponry. But when muons particles hit the two Argosian heads in the installation, the piece comes to life, lighting up like a Christmas tree. If you listen closely, you can almost hear the faint snap, crackle and pop of the universe at play.

The piece was originally commissioned as part of an Arts at CERN residency. Since 2011, the program has welcomed a variety of artists to make work in the CERN labs. Artist Yunchul Kim’s work spans a variety of disciplines, including poetry and physics. Kim used the opportunity to explore particle experiments as well as “the possibility of controlling the propagation of light through colloidal suspensions of photonic crystals.”

In making the invisible seen but also strangely felt, Argos somewhat resembles Brion Gysin’s Dream Machine with its array of flickering lights playing in random patterns, creating a trance-like state of euphoria. In capturing the dazzling firefly existence of muons, the piece traipses across all kinds of different lines: technology, emotion, beauty and some weirder stuff.

Muons pass through us constantly. In some atomic corner of our being, I wonder if they register, especially as we’re made aware of their existence. In quantum physics, awareness itself can change the outcome of experiments. Perhaps the same is true of art.

After all, we humans are also built of cosmic material, primarily carbon, created in the belly of a star. Does like call to like? Can you truly feel things like muons or cosmic rays when their existence is suddenly made visible and apparent?

The exhibition’s introduction places the individual pieces in the show into this human context: “Ancient cosmology was rooted in our meticulous observation of natural patterns. Hundreds of thousands of years in the making, the most sensitive, sophisticated and flexible instrument of observation may still be us; our frail bodies and creative minds.”

It is these frail bodies — eyes, ears, noses, skin that feel the universe at work — funnelling the infinity of time and space through the smallest of apertures. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Ralf Baecker’s Mirage.

In one darkened room in the gallery, a red wave of light undulates slowly on a wall. It is both ethereal and corporeal, with allusions to blood vessels, ultrasounds and lava flows. The references arrive thick and fast like a red-hot magma flow, even as the piece itself is strangely soothing.

Sitting in the darkness, I felt my mind drift off, making odd random connections, thinking about roaming black holes, volcanology, free-floating stuff, as gossamer and easy as a floating soap bubble. The experience was so pleasant, I could easily have stayed for hours.

The experience of Mirage is only one aspect of the work, the actual apparatus required to make it happen is another. The installation, consisting of an aluminium profile, custom electronics, muscle wires, line laser module and flux-gate magnetometer, works by registering the magnetic field of the Earth, partly determined by the planet’s interactions with the solar activity. These readings are then fed into an unsupervised algorithm. If the term unsupervised algorithm makes you giggle like a school kid, then come over here and sit with me.

Do you really need to know what a flux-gate magnetometer is in order to experience the piece? The short answer is not really, you can simply sit in the darkness, let Mirage work its way through the deepest parts of your body, while you watch the serpentine crawl of crimson light.

For the more curious and technically minded folk or the people who just need to know stuff, hang onto your hats. There are loads more details to the work.

Mirage was inspired by the Helmholtz Machine, which if I understand it correctly, and I could have it terribly wrong, uses the principle of a wake-sleep algorithm. While the machine is awake it is trained to take in sensory input. In its sleep cycle, this information is then transmuted into dreams. The dreams are rendered into visuals through the use of a mirror, 48 muscle wire actors and a laser. Just don’t look directly at the laser.

The notion of altered consciousness and the dreaming mind pop up in Mirage as they did in Argos.

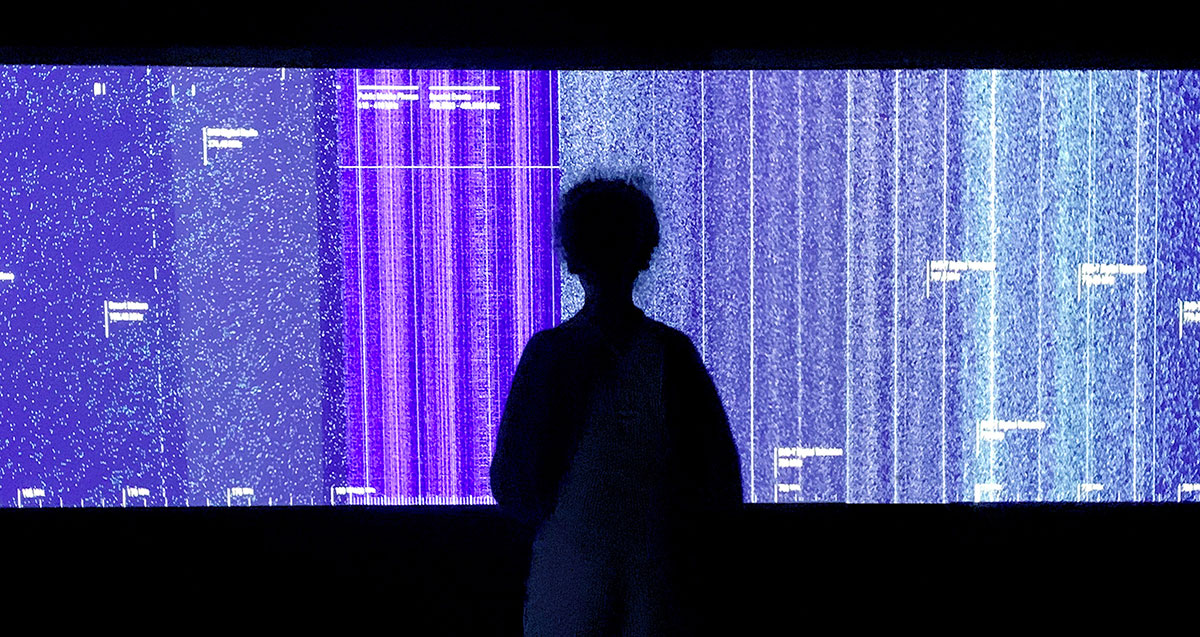

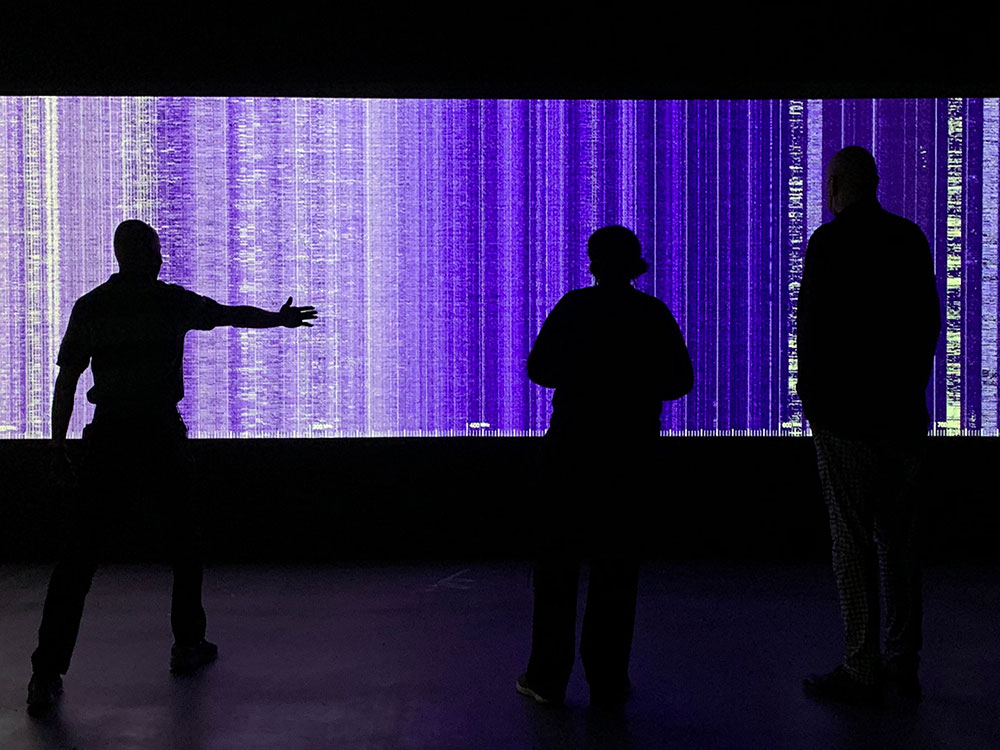

In Richard Vijgen’s interactive installation Hertzian Landscapes, this dreaming quality becomes something of a nightmare. Hertzian Landscapes is a bit more of a combative experience than the two previous works. The technological specifics of the work are again considerable, but in short, it visualizes the massive dumps of data that fill the atmosphere around us, everything from radio transmissions to medical implants, the very air around us buzzing with near-obliterating levels of information.

In making this invisible barrage seen, a digital receiver scans the radio spectrum, running the length of the piece like a robot sentinel. This information is turned into a cascading waterfall, composed of different coloured bars of light. It’s more than a little Matrix-like. If you stand close to the panoramic screen, the piece reacts to your body and the action changes.

Stand in one spot long enough and it becomes like your own personal mini-rave, full of thudding beats and a light show. Step back, and the frequencies reassemble into their former patterns. Jump in, jump back out, and do it all over again. Hey, it’s a disco dance party!

Something of this rave culture experience is carried on in Through the AEgIS from the U.K. duo Semiconductor (artists Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt). Semiconductor were awarded an Arts at CERN residency in 2015, during which they were inspired by the Antihydrogen Experiment: Gravity, Interferometry, Spectroscopy.

The work “looks at how antimatter responds to gravity, you see pions, protons and nuclear fragments flying out from ‘annihilation sites’; these particles ionize a photographic plate which when developed reveals their trajectories as varying sized tracks.”

So, what does that mean? And more importantly, what does it look like?

A two-part experience, Through the AEgIS offers an animated version of these gravitational reactions. It calls to mind a few different things: a laser light show, with plenty of shooting beams and miniature explosions, a cosmic war of sorts, and yes, it is a little bit disco. The second half of the work freeze-frames the action into a single, albeit deeply dense image that resembles the deepest spangled, star-studded expanse of the universe.

In bringing together the worlds of science and art, the works in Indivisible do something very interesting, which is offer up experiential moments. These are artworks that make you feel things, as opposed to the more passive act of looking at things. It goes beyond engagement into a new bodily territory. They get inside you, even as you get inside them.

These experiences can be simultaneously disorientating and sublime, vast and minute, hilarious and profound, but they are ultimately a reminder that while the universe is busily going about the business of being the universe, art still offers one of the most direct and immediate ways to access the action.

Indivisible is on view at the New Media Gallery in New Westminster until Aug. 14. ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: