For anyone who has ever argued with Siri, The Imitation Game: Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence may come as a relief. The new exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery explores the influence of AI on everything from fashion to film. It also demonstrates you’re not the only one who is alternately charmed by, resentful of, fascinated with, and despairing of our dependence on technology.

It’s hard not to think of an aspect of your life that isn’t intimately intertwined with some form of tech. We all know the relationship between people and machines isn’t always harmonious. My sister is convinced the GPS in her car is trying to kill her by constantly demanding that she pull U-turns in the middle of traffic. Amazon’s Alexa apparently told a child to do the penny challenge, which meant touching a coin to a live electrical outlet.

A power struggle seems to be brewing. Humans have long insisted on having their way, but technology is rearing up on its hind legs, demanding autonomy. The notion that our creations are evolving out of our control is an old story, but artificial intelligence has given it new life. To tweak the immortal words of Dr. Frankenstein, “It’s AI ALIVE!”

The Imitation Game’s title was inspired by tech icon and mathematician Alan Turing’s idea that a machine able to convince a human that it was also human demonstrated artificial intelligence. Turing’s work as a cryptologist during World War II is believed to have yielded intelligence that defeated Hitler. In 1954, he killed himself at age 41 by eating an apple dipped in cyanide after being criminally charged for being in a relationship with a man.

Before his death, Turing appeared to have some misgivings about machine intelligence. “It seems probable that once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers,” Turing mused during a 1951 lecture. “They would be able to converse with each other to sharpen their wits. At some stage therefore, we should have to expect the machines to take control.”

Ok, computer

Are we there yet? Don’t ask Alexa — she might get some notions. But what happens when the machines shuck off their masters and take on a life of their own?

The idea of revolting robots, featured in the exhibition, has fuelled film and literature for almost as long as machines have been around. There is a direct line from the sexy robot in Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis to the female automaton in Ex Machina. Both films take as their premise the notion that technology, freed from human control, can wreak untold destruction. Also, lady robots still do sexy dances for the benefit of the male gaze. So, perhaps some things haven’t changed.

References to other cinematic explorations such as The Matrix and Blade Runner are also featured in the exhibition, but one of the most unsettling works is Ben Bogart’s reworking of Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Part of the artist’s Watching and Dreaming series, Bogart set up an AI program to view science fiction films and deconstruct them. The resulting fragments of sound and image are rebuilt into something related to the original but also distinctly different.

Even though the piece itself is beautiful, shot through with metallic silver and viscera-red colour, there is something that makes me feel deeply uneasy about it. The familiar, rendered strange and uncanny, is implicit, but so is a new kind of perception, muttering away to itself as it learns.

I didn’t last more than a few moments watching the reworked film before fleeing the gallery screening room. The notion that the AI watching the film might get a few ideas from HAL 9000 also crossed my mind. As folk might recall, HAL 9000 is the AI program that runs the spacecraft in 2001 and slowly loses its mind after it murders all of the human crew members.

From human hearts, robot art

Other relationships featured in the exhibition are easier and even playful.

London-based artist Sougwen Chung fell into drawing with robots when she built her first robot drawing arm, D.O.U.G. The first iteration was meant to shadow Chung’s movements as she drew, but what worked perfectly in theory was somewhat different in reality. In a TED Talk about her work, she is open about the role that accident plays, explaining that with each subsequent edition of her robot collaborators, the nature of the work has evolved and developed in surprising ways.

Chung’s work Omnia per Omnia is given room to play out in one of the VAG’s largest spaces, with pride of place being given to a family of robots that the artist uses for performance-based work. Even stilled for the moment, the machines feel charged with a degree of purpose. Part of Chung’s practice involves creating a dataset of her drawing style that is then shared with her mechanical partners. Her blue and white images, loopy and organic, form the raw information, but from there curious new intersections arise. The line between human and AI — where one begins and ends — is hard to discern.

With a solid, almost Renaissance understanding of the human figure, American artist Scott Eaton has parlayed his skill as a draughtsman into a work that walks the line between the sublime and grotesque, often in the same piece. This twinned quality is most evident in Entangled II, where melting morphing flesh takes on a bright, almost plastic quality.

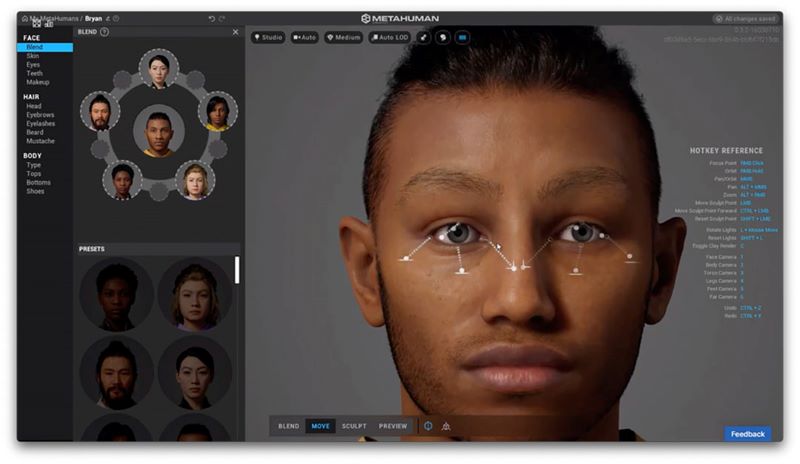

Like Chung, Eaton’s work is collaborative in nature. Working with AI assistants, he trains software to turn everything into a figurative form, converting the artist’s drawings of the human body into 3D renderings.

Eaton’s digital images resemble a Hieronymus Bosch orgy by way of Jeff Koons and the Chapman Brothers. It’s raunchy sex mixed with the Book of Revelations. Other pieces of Eaton’s that make use of choreographic language are easier on the eye, elegant and sculptural in their approach.

Only as good as their human makers

The VAG’s senior curator Bruce Grenville and co-curator Glenn Entis have been planning the show for a while, but AI has taken greater prominence over the last three years. Mass surveillance systems and facial recognition software has been connected to all kinds of ominous stuff. Public distrust of the technology runs deep over stuff like deep fakes.

The ubiquity of machine interactivity is hardwired throughout the show, moving like a live current through the different objects and installations. The use of AI in video games, computer-generated imagery, virtual reality and architecture is commonplace. (A scale model of Bjarke Ingels’ Vancouver House design pops up like a beehive on speed).

But the ways in which AI influences and controls the actions of humans are becoming increasingly hard to see. Things like preference engines — along the lines of “If you like that, you’re gonna love this” — guide our choices in everything from Netflix movies to online shopping.

You can’t blame the machines. They are only as good as their human makers, and lord knows humans are fallible. Machine malfeasance take its cue from human imperfection, including racial bias and how we wage modern war with autonomous weaponry.

Unnatural nature

When AI messes about with other species, there is something even more unsettling about the process. American-Israeli artist Neri Oxman’s Golden Bee Cube, Synthetic Apiary II, 2020 uses real bees who are proffered silver and gold to create their comb structures. While the resulting hives are indeed beautiful, rendered in shades of burnished metal, there is a quality of unease imbued in them. Is the piece akin to apiary torture chambers? I wonder how the bees feel about this collaboration and whether they’d like to renegotiate the deal.

When Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, created a machine called Moth in 1949, he might have had some inclination of where things would go. As Wiener stated of the technology: “Those of us who have contributed to the new science of cybernetics thus stand in a moral position which is, to say the least, not very comfortable. We have contributed to the initiation of a new science which… embraces technical developments with great possibilities for good and for evil.”

Wiener’s moth machine, a bumptious thing that somewhat resembled a Roomba vacuum cleaner, evolved into the sleek smooth-voiced entities of today that play music, open doors, set temperature controls and generally work to provide people with easier, more pleasant experiences.

The relationship between humans and machines has been long in germination, but the fullest flower has sprouted in the last seventy years, as computing power has exponentially increased.

But even as people embrace technology with almost embarrassing gusto — hello, sex robots! — we do so thinking that we retain the ultimate power.

But that confidence may be coming to an end.

Long after HAL 9000 and Blade Runner’s truant replicants slipped the yoke of human control, the number of films that make use of the idea of a technological uprising continue to proliferate. And, of course, the ultimate robot dream of destruction that humans don’t want to know they have.

It’s almost as if we are rehearsing something we know is on its way.

The Imitation Game is a big show, filled with big ideas, but it leaves us with larger questions.

Can machines be creative in the same fashion as humans, or will they copy what they have been given? What does a new form of intelligence really look like? What does it experience, and will we recognize it when it arrives?

Is it already here? ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: