Sometimes when I visit an art gallery, I walk around, look at the work and feel only mild interest. But sometimes the opposite happens: a flood of feeling comes roaring in like a tsunami. Assembly, the latest exhibition at the New Media Gallery in New Westminster, contains an almost oceanic swell of ideas and emotion.

The show consists of three works: Elizabeth Price’s A Restoration, Fiona Tan’s Archive, and an installation from Swiss artist Zimoun with the somewhat long-winded title: 278 prepared dc-motors, cotton balls, cardboard boxes 51 x 51 x 51cm, 2010/2021.

Each individual piece is fascinating on its own, but how they function, interrelate, converge and diverge together is truly extraordinary. Such is the alchemy of good curation. Even more interesting is the quality of feeling layered over the show, like a greyscale of emotion, wandering from the palest dove shade to colours far grittier and darker.

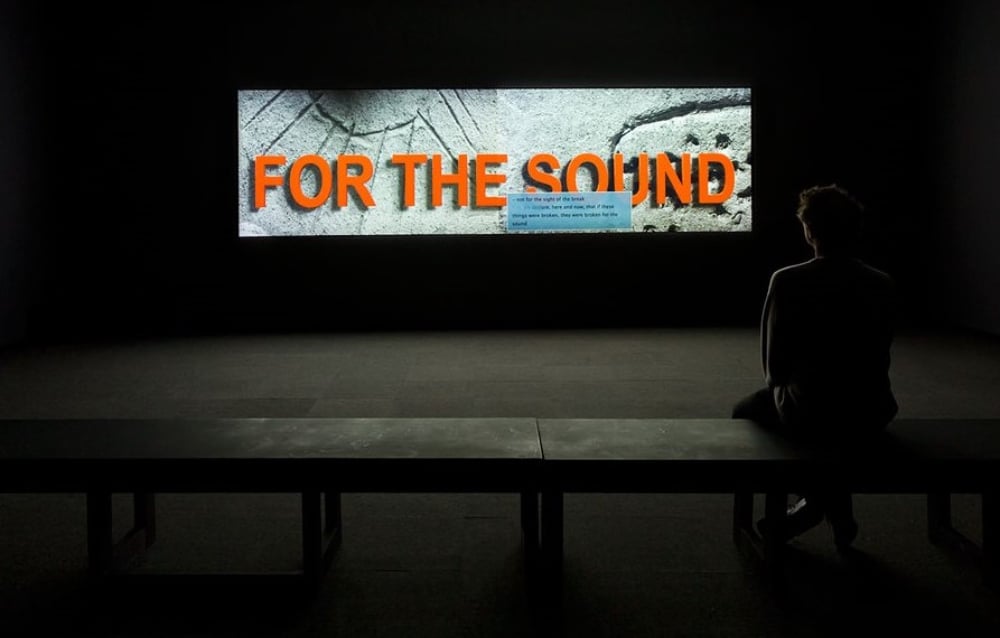

Price, who captured the British Turner Prize in 2012, has fashioned a video installation that occupies the interstitial territory between music video, spoken word piece, archeological artifact and something slightly undefinable.

Her piece, A Restoration, was originally created for the Ashmolean, Britain’s oldest public museum. Constructed in 1683, the Ashmolean houses an extraordinary collection of artifacts and art, including drawings by Michelangelo and da Vinci, paintings from Picasso, Cézanne and Rubens, as well as the usual antiquities, pottery and generally old stuff. Most notably for Price’s work, the Ashmolean also contains the bequest of archeologist Arthur Evans.

Evans is something of a curious figure in archeological history. His discovery of the Bronze Age city of Knossos on the island of Crete both cemented his reputation and undermined it. Consisting of more than 1,000 chambers and rooms (some practical and other more esoteric in their function), Knossos and its mazy spaces recalled mythological figures like King Minos. On the basis of his discovery, Evans began to extrapolate about the society that might have existed on the site, and before long his speculations spiralled wildly out of control.

Evans’s habit of straying from the path of scientific rigour and making shit up proved a perfect leaping off place for Price.

A Restoration takes the idea of archeological imagination run amok to an entirely new realm. In the work, Price creates a strange semi-dream world run by Stephen Hawking-voiced museum administrators, an AI program that has drifted from its stated task and begun to create fantastical visions of a fabled lost utopia. In this great city, carved deep into the earth, everything a society might need to function well is accounted for.

There are places to bathe, eat and gather, all of it collective and idealized in its intent. But this is only one aspect of the piece. It is a multi-layered creature: one-part speculative fiction, another part carefully researched exploration of the things actually contained in the Ashmolean itself.

In interviews, Price explained that many of things in the museum’s collection have been documented in different ways and through different technologies since the place opened in 1683. An ancient vase, for example, might be captured in drawings, etchings and digital photographs, so that the artifacts move through time in different forms of representation.

Part of Price’s work is an attempt to parse the interpretations of the past through the lens of the current cultural moment. In other words, where we are now informs what we understand about history. In this, both artist and archeologist are equally implicated. Both arguably work in the realm of imagined possibilities.

Anyone who thinks video installations cannot be thrilling, just sit through Price’s work a few times. You’ll come out reeling. Far from a desiccated, crepuscular museum piece — full of vitrines, dusty tablets and pottery shards — A Restoration feels like a missive from another possible, far kookier world. The wealth of associations it conjures up come thick and fast: the pop sensibility of Laurie Anderson’s Big Science mixed with Disney’s early internet movie Tron.

I watched it twice and could have easily watched it six more times, such is the density of the information and experience. But in spite of the multiple layers of meaning, the work has a gleeful, rebellious, almost riotous edge that is positively exhilarating. In its escalating rhythms it builds to a glorious conflagration, as sharp and singular as shattered glass.

Fiona Tan’s Archive, also a video installation about a lost world, is decidedly different in tone than Price’s rock ’em, sock ’em work. Archive, as its title suggests, is a recreation of a great lost library inspired by the work of Paul Otlet. Often dubbed the father of information science, Otlet was an odd fellow. In addition to being an entrepreneur and inventor, he harboured idealistic notions about what unfettered access to information could offer humanity.

With this ethos in mind, he embarked upon the creation of his masterwork, the Mundaneum, a veritable city of knowledge that would house all of the world’s information under one roof. More than simply a library, it was in some ways a precursor of Google’s World Brain Project.

At the height of its fame in 1934, the Mundaneum included more than 15 million index cards, organized in custom-made cabinets. But when the armies of the Third Reich rolled into Brussels, they took over the site, ransacked the collection and installed Nazi artwork in its place. Otlet died in 1944, essentially penniless and forgotten.

Tan resurrects his great project in a fully realized, full-scale model, envisioning it as a 3D fly-through filled with endless rows of cabinets and shelves, all of it freighted with the information that Otlet believed would unite humanity in peace and understanding.

In sitting through the recreation of Otlet’s work, another film came to mind: Stan Neumann’s documentary Language Does Not Lie, about the assault on knowledge and culture undertaken by the Nazis who set about trying to reorder society by reordering words themselves. The film is based on the diaries of linguist Victor Klemperer, who carefully recorded and analyzed all of the denigrations made against words and their meaning during the Nazi regime.

It is hard to watch Archive without having a creeping feeling of dread steal over you, a sinking sensation that one day, all of the many things that humans have busied themselves with over the past millennia will fall to dust and silence. But even before that happens, any understanding will fail in the face of lost and stolen knowledge.

So, where does truth ultimately lie? Perhaps in the body. Which brings us to the third part of Assembly.

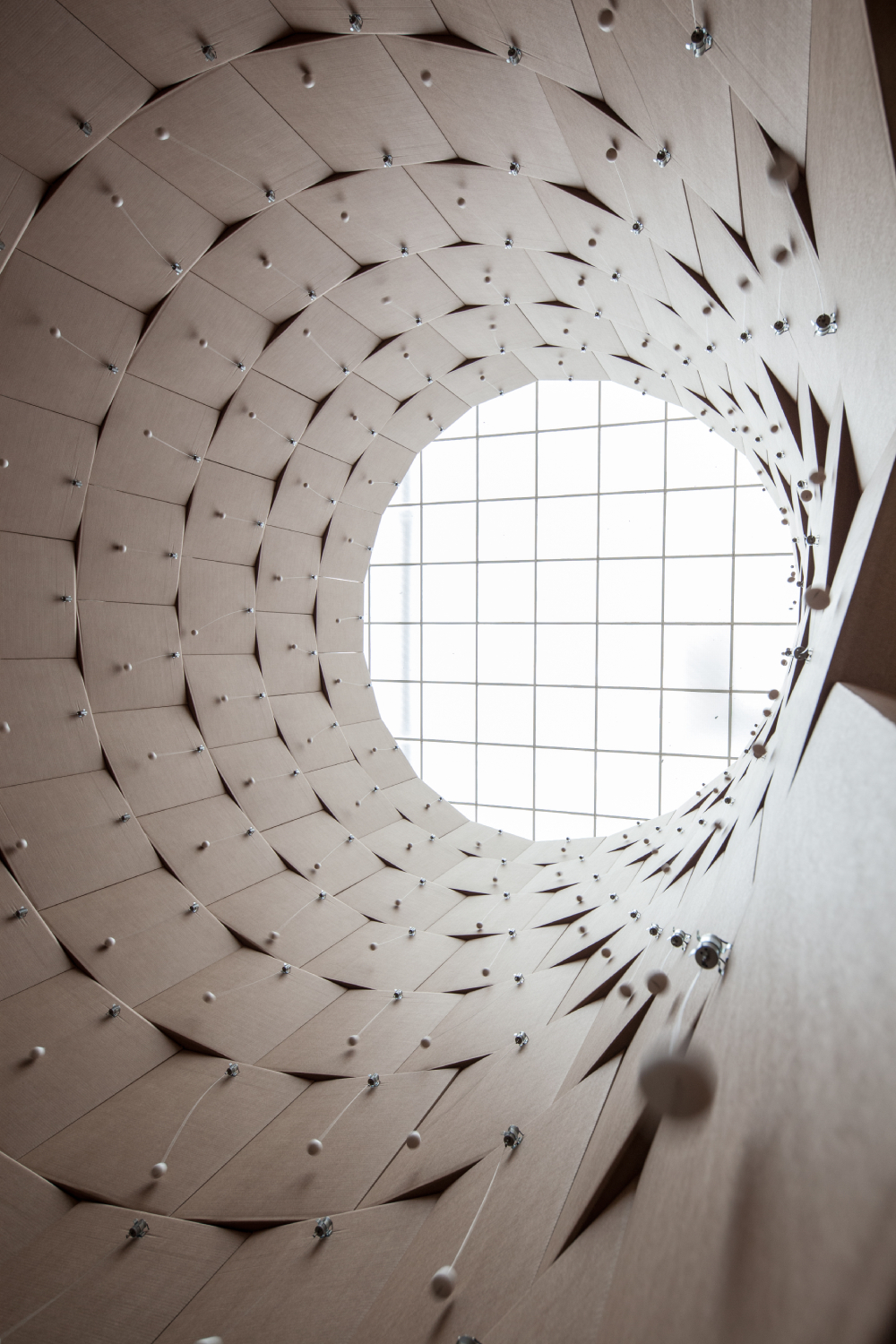

Zimoun’s installation, in the centre of the gallery, functions as an interesting conduit between Price and Tan’s work. As the title states it’s composed of 278 DC motors, each linked by a length of wire to a hard cotton ball. Each mechanism is attached to an ordinary cardboard box. Grouped in a circular tower, the boxes tower to the ceiling, and when you enter inside the space, all you can hear initially is the thunder of the assembled machines at work

The intent is to allow for each individual component to develop its own autonomous pattern within the greater body of the collective. Some balls are swinging around willy-nilly, while others meander back and forth like they can’t be bothered to get too excited. After a time, each ball appears fully personified, with different quirks and traits. Some are jaunty, others despondent.

All the while, the sound of the collected machines recalls a host of references. Factories, the white noise of a sonogram, or the jackboot trudge of armies on the march are immediate evocations. The longer you remain in the heart of the piece, the more the sound wends its way into your body. At a certain point the roar becomes strangely calming, like being inside an enormous seashell.

As a fulcrum between the two video installations, Zimoun’s work strips away the verbiage that often attends contemporary art and just allows a body to be for a moment, suspended in sound, born aloft by pure feeling.

Although it is no less complex than the other works in the show — all three share commonalities of sound, order and information systems — it provides a different, more embodied and physical way into the ideas that Assembly offers.

If you press an ear very gently to the outside of any of the individual cardboard boxes that make up the installation, you can hear a sound that is echoed inside your own body, the steady metronomic beat of your heart.

Catch the 'Assembly' exhibit at New West's New Media Gallery until Dec. 5. Details here. ![]()

Read more: Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: