What more is there possibly to say about food? It’s been covered in every imaginable medium — painting, writing, film, photography — almost to the point of total exhaustion. Anyone with a smartphone can document their meals and share them with the world.

But just when you think there couldn’t be anything left, along comes something like Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography that reinvents the wheel all over again. Actually, that wheel is an oozing hunk of melting brie and an overripe red pear, photographed by American photographer Irving Penn. Garnished with a single black ant, the image traipses along the borderline between luscious and obscene.

Feast for the Eyes, now on at the Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver, was curated by writer Susan Bright and editor Denise Wolff from New York’s Aperture foundation. The project was originally conceived as a book, and the tome that accompanies the show weighs as much as a full-size turkey.

Although many of the images in the show are straightforward, it’s the stuff that originates from the Freudian no-man’s land between desire and overindulgence that squirms in your mind’s eye. Good, gross, yummy, icky, it’s all mashed up together in a confusing tangle of emotion. The feelings produced by such an overwhelming abundance of colour, image and content might require one to lie down in a darkened room afterward and sip some flat tap water.

The show is organized into three different sections — Still Life, Around the Table and Playing with Your Food — each laying out all the things that food can do and be, other than simple sustenance. Comfort, culture, fashion, plaything, garbage, sexual aid, feminist statement: it’s an endless buffet, stretching gluttonously as far as the eye can see.

The list of artists is equally impressive, 60 different sets of eyes and palates running the gamut from 1970s feminist performance art to fashion photography. It includes Henri Cartier-Bresson, Nan Goldin, Man Ray, Vik Muniz, Helmut Newton, Irving Penn, JR, Ed Ruscha, Carolee Schneemann, Cindy Sherman, Stephen Shore, Andy Warhol, Weegee, Edward Weston and Nobuyoshi Araki, to name a few.

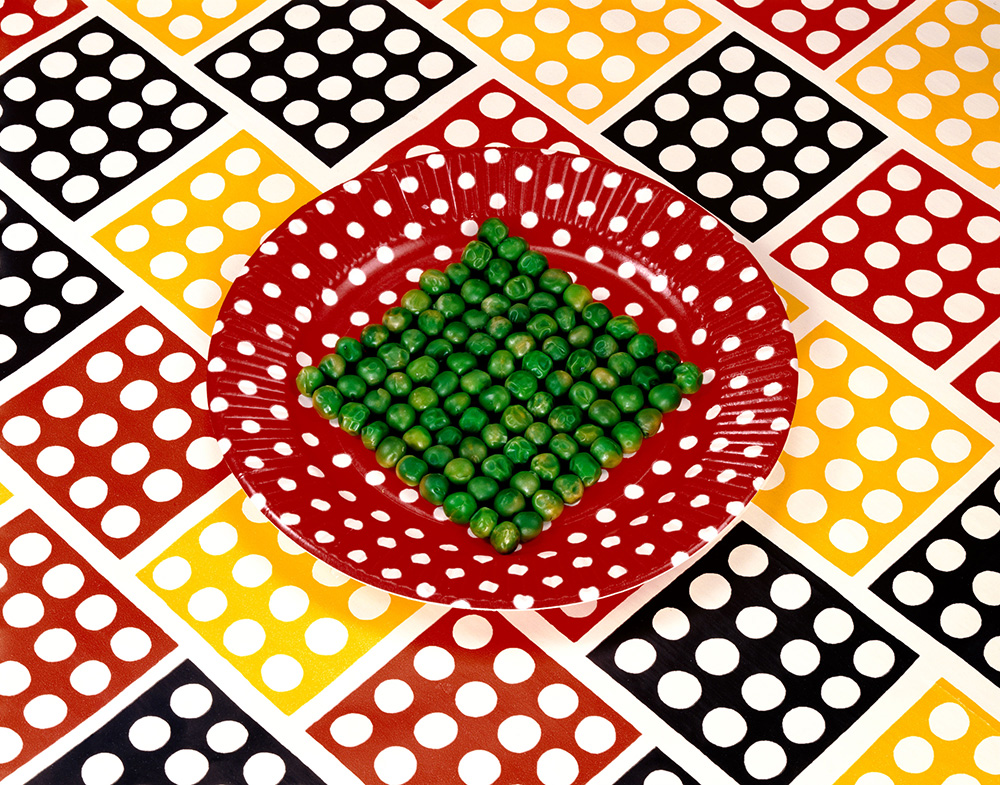

The first grouping of work, Still Life takes as its organizing conceit the long tradition of painting foodstuffs. But even here, in photography’s very early days, the images of cabbages, peppers and peas stray into strange territory, whether it’s Edward Weston’s Mapplethorpe-esque pepper, sensuous and corporeal as a human body, or some of the first-ever food photos, taken by Charles Jones, a curmudgeonly English gardener who died in penury.

A cache of Jones’s work was discovered at a boot sale in London in the late ’80s, a happy accident that vaulted him into the pantheon of early food photographers. His images of green peas tucked demurely in their pods or the crenellated ruffles of purple cabbage have genuine personality. Unlike later images, these vegetables possess a curious gravity, nobility even, that radiates out, demanding a curtsey or some other form of deferential politeness.

Things get a little kookier in the exhibition’s second section Around the Table, which details how people share food. From banquets to family dinners, food is soaked with social, cultural and familial traditions. Any celebrations — weddings, birthday, parties, holidays — demand different kinds of offerings. Most especially cake! Send more cake!

Cookbooks from every corner of the globe are on display, along with Weight Watcher recipe cards that are inadvertently and thus hilariously grotesque. The worst food combinations in human history, such as Chilled Celery Log, Crown Roast of Frankfurters or the ominously titled Inspiration Soup, are enough to make you never want to eat again. So, maybe these recipes genuinely worked.

But the bright, artfully arranged courses that pushed food as aspiration, with endless exhortations to housewives to cook to impress, offers a painful form of nostalgia. Lurking behind these images of manic cheer and salmon in aspic are darker implications, mother’s little helpers and domestic servitude.

The feminist art practice of the late ’60s and ’70s exploded the kitchen, upending not only the traditional roles of women, but taking apart the idea of food itself. In some cases, literally.

Carolee Schneemann’s performance art piece Meat Joy NYC (1964), filled with raw chicken and half-naked bodies, brought the idea of ritualistic indulgence and female emancipation to a boiling point. Even with the likelihood of salmonella poisoning, the performance (captured in grainy footage in the Polygon’s show) remains a rich and rollicking experience.

Schneemann, along with other women artists such as Martha Rosler (Semiotics of the Kitchen), introduce a sense of subversiveness and humour that is carried throughout the final section of the show Playing with Your Food. Liberated from being edible stuff, here food is both the medium and the message.

Materiality is the name of the game in Vik Muniz’s peanut butter and jelly renditions of Warhol’s Double Mona Lisa. From this sense of playfulness, it’s an easy leap into full on food porn, as embodied in the work of kinky old Helmut Newton, Joseph Maida’s sexy candy or Joan Callis’s juicy fruit pies.

Even a relatively cool eye, such as Irving Penn, couldn’t stay away from food as a stand-in for desire, as his white-hot tableau of frozen fruits and vegetables makes clear. Blueberries, asparagus and fava beans, dusted with frost but beginning to lusciously drip with colour as they thaw, are enough to make one blush.

Anyone who has ever looked closely at a tomato or a garlic clove knows how beautiful and complex food can be. The exhibition does not stint on beauty.

Wandering around just letting it slide into your eyeballs is one way to take it in, but there is wealth of meaning attached to each image. So much so that it’s almost too much, like eating a seven-course dinner and then being offered a chocolate mint. One might very well explode.

In the introduction to the exhibition suitably entitled Eye Candy, co-curator Susie Bright writes: “Food can arouse repeated and constant links between perception and memory, and when photographed, it is likewise transformed into a network of comparable connections and associated symbolic orders.” In other words, “our dreams and desires.”

A smorgasbord of every possible thing you could do with food, eating is almost last on the list, although the Polygon has helpfully installed a pop-up shop on the main floor where you can purchase a variety of local foodstuffs.

Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography runs to May 30. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: