Jeffrey Cook was only eight when he sat down in the Alberni Indian Residential School and painted a raven.

Art offered an emotional escape from an often grim life in the residential school system, and a way to connect with culture, he says.

More than half a century later, his painting will be displayed in the Museum of Vancouver, part of a new exhibition titled There is Truth Here: Creativity and Resilience in Children’s Art from Indian Residential and Day Schools.

Andrea Walsh, who first curated the exhibition in Victoria last September, said the students’ art, and the additional works that provide powerful context, shed important light on life in residential schools.

“There’s a resilience to these paintings that the school couldn’t take away and art allowed them, in these really rare moments, to express what they knew,” Walsh says. “I think all of the paintings, all the art reflects who the children felt they were at the time, and is a mirror of who they were.”

Even the survival of the students’ arts and crafts — stored in garbage bags, hidden under beds in boxes for decades — seems amazing.

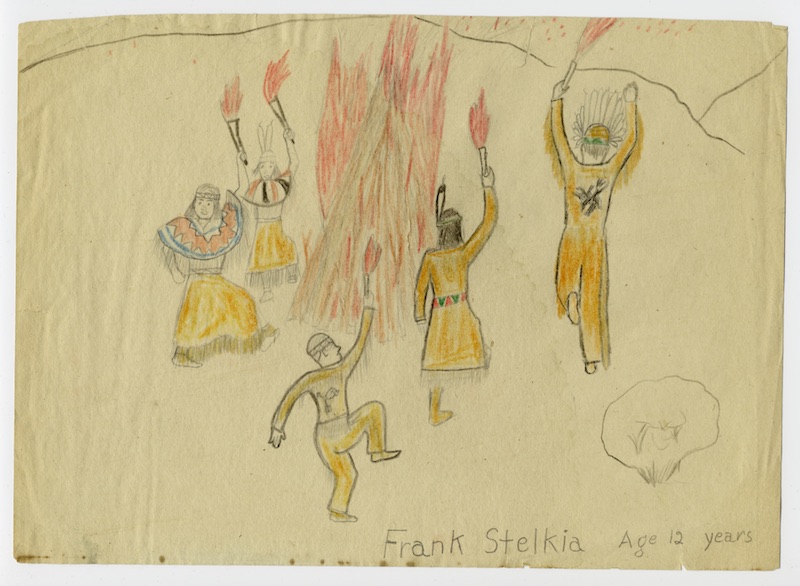

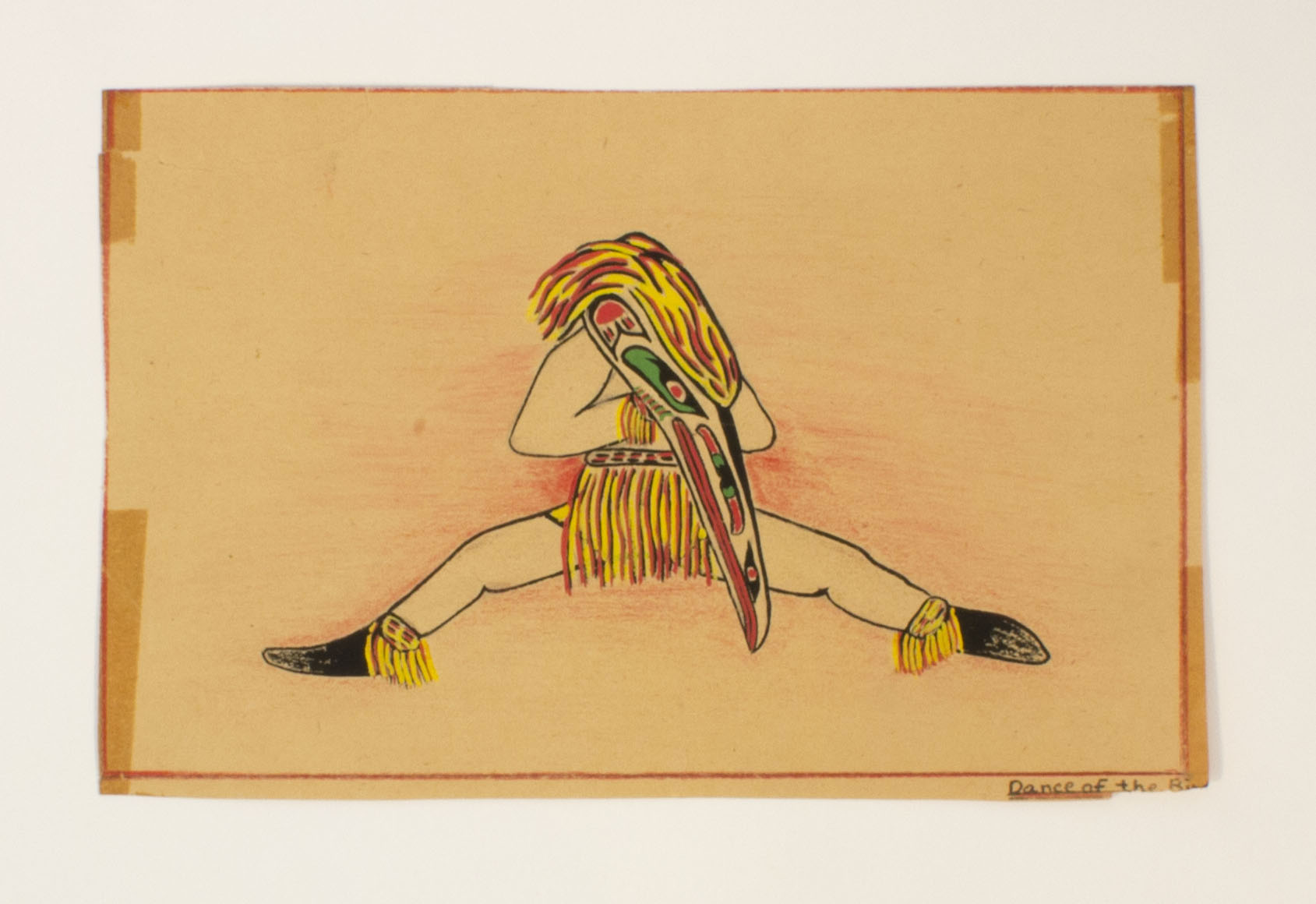

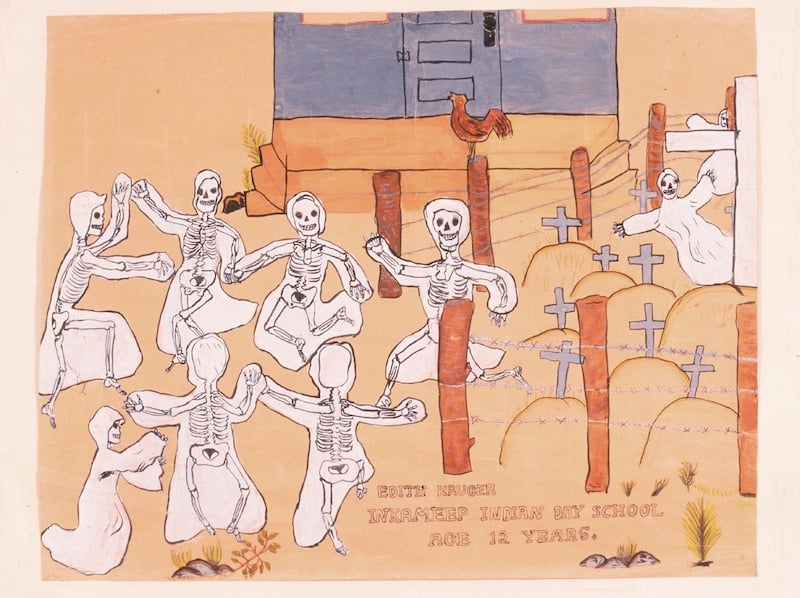

Walsh’s research began in 2000, when she collaborated with the Osoyoos Indian Band to uncover the history behind the Inkameep Day School’s collection of drawings from the 1930s and ’40s.

That led to the discovery of the story of Anthony Walsh (no relation), who taught at the Inkameep Day School in Osoyoos and encouraged students to express themselves through art. He even entered their work in the annual Children’s Wartime Drawing Competition in London organized by the Royal Drawing Society, where they won awards.

The decision to send the art to England also helped ensure its preservation. When the society offered to return the works in the 1940s, Katie Lacey of the Oliver Society for the Revival of Indian Arts and Crafts stored them, stashing them in a box under her bed.

They stayed there for 20 years until 1963, when Lacey donated the collection to the newly opened Osoyoos Museum. Other work had been burned by teachers who followed Anthony Walsh.

Almost 50 years later, Andrea Walsh began uncovering their history. Since then, she has helped return works to survivors.

Art and handiwork from the Alberni Indian Residential School, the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Alert Bay, the Inkameep Day School in Osoyoos, and the MacKay Indian Residential School in Manitoba will be showcased, with many items on loan from the personal collections of survivors and their families.

Visitors will experience paintings, buckskin costumes and arts and crafts, accompanied by audio and video recordings of plays and songs from the children. Sharon Fortney, the museum’s curator of Indigenous collections and engagement, helped to bring the exhibit to Vancouver alongside some new pieces, including artworks from other museums like the U’Mista Cultural Centre and the Osoyoos Museum Society.

The arts and crafts created by children attending residential schools represent some of the only positive memories from an environment that was often deeply hostile to Indigenous culture, says Walsh. They are unique and imbued with profound emotional significance.

They are also powerful and astounding in their level of technical skill. All of the work refers to the land in some way, Walsh says, and every single piece in the show is tied to a sense of belonging.

“There’s a painting by Chuck August of Meares Island, and when you look at the painting, the topography is perfect,” she says. “It’s taken from his mind, and the perspective of being on a fishing boat. When he talks about it, he talks about his grandparents and where they fished for certain kinds of fish.”

A survivor remembers

Cook, one of the hereditary chiefs of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation on Vancouver Island, attended Alberni Indian Residential School from 1956 to 1969. Art was an emotional escape from residential schools, he said.

The survival of his raven painting is another story.

Robert Aller was the Alberni Residential School’s art teacher. He gave the students free rein to explore their lives as they existed beyond the school.

“He let all the students express their own minds rather than just show them how to draw and paint,” Cook says. “Just let them be a free mind. A lot of [the art] had to do with culture in your home life, and we didn’t think too much about painting residential school life.”

Aller saved the students’ work in garbage bags. When he died in 2008, it was willed to the University of Victoria. The director of UVic’s gallery knew of Andrea Walsh’s work with the Osoyoos band and asked her to assess the Aller collection.

Walsh worked with students in the university’s anthropology department, where she’s an associate professor, to document the paintings and began to contact survivors in 2012.

Cook cherishes the raven painting, because it’s the only keepsake from his childhood. The exhibition project was initially very emotional for him, he says, but as it went on he accepted it as part of his history.

He was troubled, however, to find this story was not part of other people’s histories.

When survivors held panels to talk about their experiences, they found that people hadn’t heard of residential schools or knew how difficult the experiences were. “Even people my age in Port Alberni didn’t realize there was a residential school here,” Cook says. He wants the show to focus attention on this part of B.C. history.

Fortney says although the exhibition highlights some of the more positive aspects of people’s experience in the schools, it’s important to remember the broader experience of the students.

“We don’t want people to think this is typical; these are actually the exceptions,” she says. “It was very special that the teacher, Mr. Walsh, encouraged them to express themselves.”

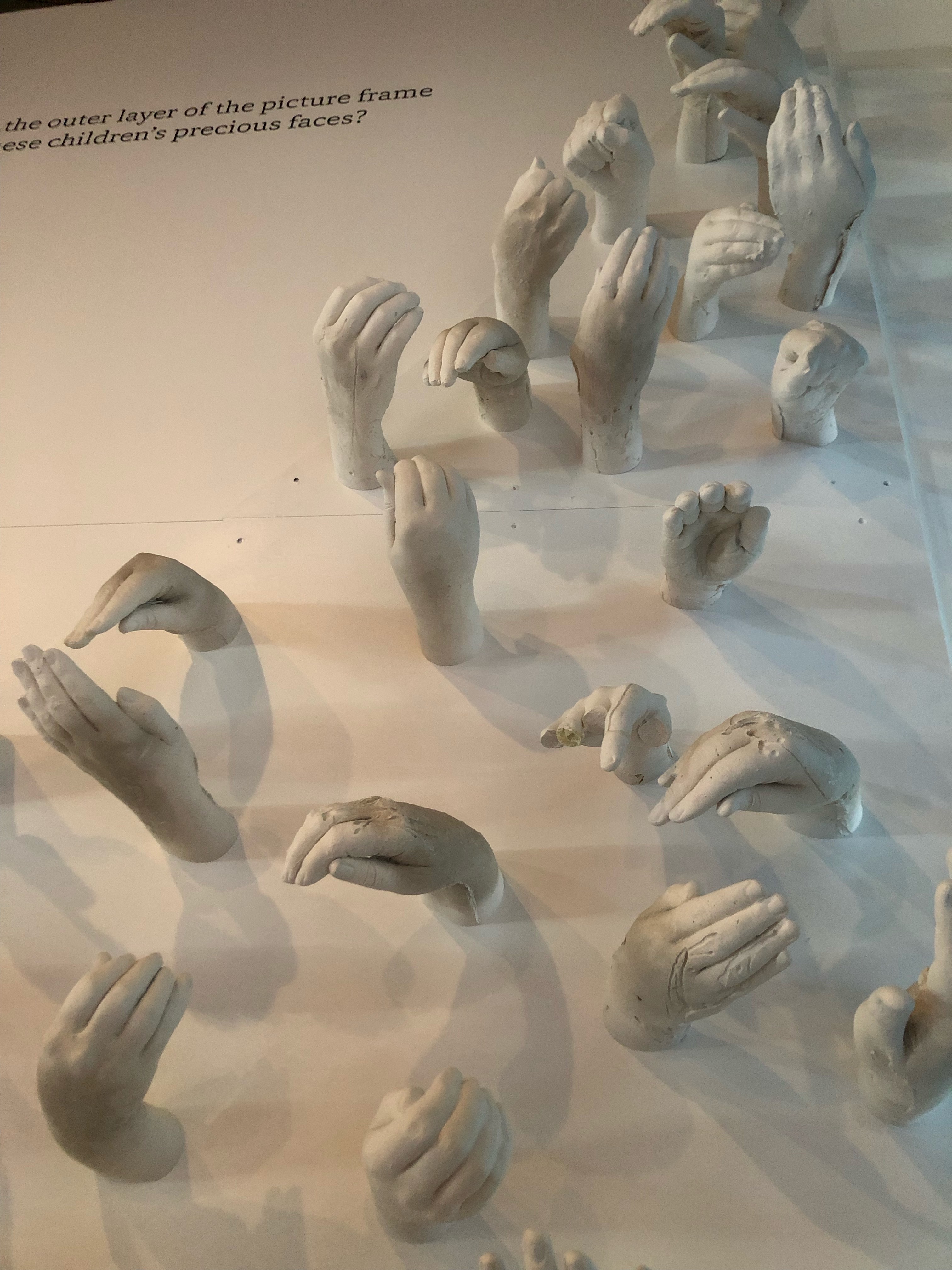

Artist Roxanne Charles from the Semiahmoo First Nation was by commissioned the Capture Photography Festival to provide context and a personal response to the exhibition.

Charles said that when people first enter the exhibition, there are two photographs of a boy and a girl on each side of the entrance, both children who attended residential school. Woven cedar hangs above the images.

“That’s an honour guard for people to walk through,” Charles says. “That’s meant to honour the survivors and pay respect to all those children who didn’t make it home.

Charles also made castings of 176 hands, which are mounted on the wall, including one of the hand of her grandmother, who attended St. Mary’s Residential School. Children’s hands are mixed with adults and elders. Charles says the hands are meant to be touched. Combined with the smell of cedar, this kind of physicality adds to the depth and emotional weight to the exhibit.

Charles also included medicines such as sage, wild tobacco, sweet grass, cedar and lavender, as well as fabrics for people to make prayer ties, which can then be tied to metal prayer hoops. She says ceremony and prayer are important aspects to her art.

“I wanted people to have something that they can work or act on, because I think there’s going to be a lot of uncomfortable feelings in the space,” she says. “I think that allowing people something to do could help.”

Consent and recognition of artists

Consent is an essential part of the exhibition. Every piece of art is presented with the permission of the family or the artist.

“Ninety-nine percent of the time, [Indigenous] children are anonymous [in historical photos],” Charles says. “I think that the reason this show is important is because it interrupts the narrative of anonymity, and it makes us stop. It allows us, in the words of [Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner] Marie Wilson, to witness this.”

Walsh says the exhibition goes beyond statistics and makes the stories of residential schools more real.

“We can understand those terms on a human scale, as opposed to these anesthetized numbers of 150,000 kids, 139 schools,” she says. “That’s why I named the exhibition There is Truth Here — because truth is much more nuanced than facts.”

There Is Truth Here opens Friday at the Museum of Vancouver, 1100 Chestnut Street. For more information, go here. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: