- The Great Gould

- Dundurn (2017)

Some 60 years ago, Canada was a small, cold country still trying to shake off the remnants of colonialism. Just graduating from high school was an intellectual achievement, and people who actually attended post-secondary were assured of some kind of work — often in the U.S.

Nevertheless, something was going on in mid-century Canada. Some ex-ceedingly smart people were at work in the universities, and beginning to draw attention from outside the country. Harold Innis was one of the earliest, framing new concepts of communication and defining Canada as an east-west country, not a northern appendage of the U.S. Marshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye, in their very different ways, offered insights into both new media and old literature — quietly subverting international orthodoxies and drawing surprised attention from scholars around the world.

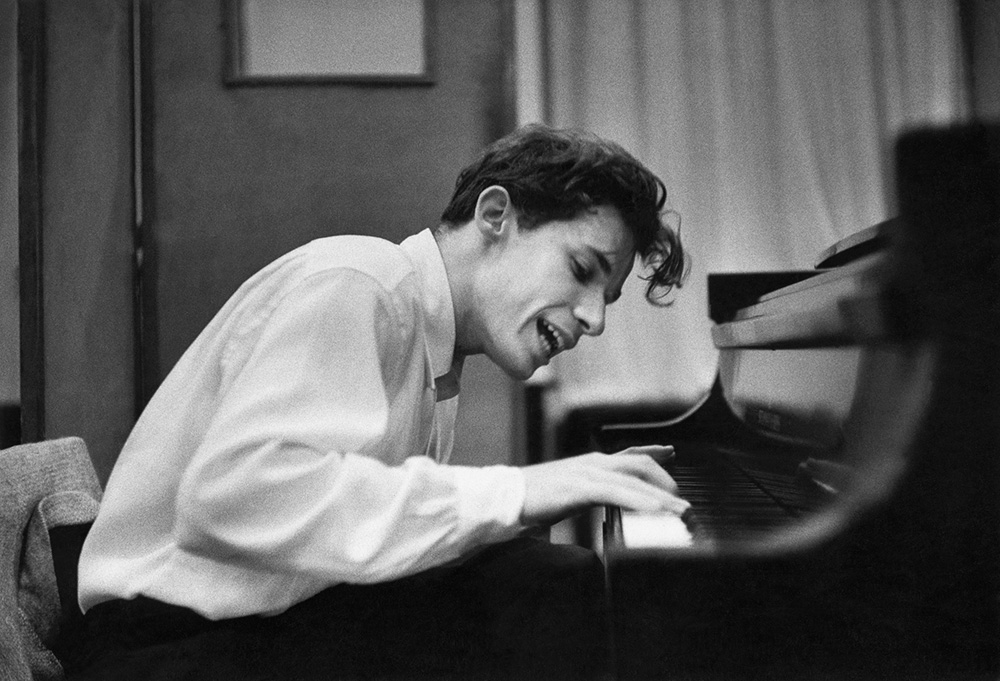

At the same time, Glenn Gould was beginning to draw attention as well. Without being quiet at all, he was subverting the world’s musical orthodoxy. Classical music wasn’t just for the refined upper classes, something to pretend to listen to while displaying one’s jewels; Gould made it wild.

Peter Goddard, in his short, brilliant book The Great Gould, tells a story about his parents returning home after hearing the young Gould at the 1956 Massey Hall recital. Gould was already famous, and Goddard’s piano-teaching father had wanted to see what all the fuss was about. Goddard asked his father what he thought. After a pause, his father said:

“We all know the pieces he played, or most of them. We’ve played the same notes and have heard ourselves play them. But he made it seem we’d been playing different things all along.”

A musical intelligence

Countless other musicians, and audiences, came to feel the same way. Never mind the astounding technical virtuosity and the physical strength it required; Gould was less a musician than a musical intelligence, living in a world the rest of us barely heard, let alone understood. When you read Hamlet or King Lear, Shakespeare takes over your brain and makes it think his thoughts. It’s astounding and exhilarating and frightening. You’re not sure what the experience was all about, except that it’s a glimpse of another order of being. Listening to Gould is like that.

But he was also a showman, ready to shock his audiences. His first American TV appearance was with Leonard Bernstein conducting (Gould starts at about 15 minutes, but watch the whole introduction). It showed him as an elegant young man in evening dress, suddenly transformed into a mad saint, lost in a trance yet hitting every key precisely, his humming and wordless singing just another part of his interpretation.

Gould might have enjoyed a successful career just as a mad saint; plenty of rock musicians were doing just that in the 1950s and ’60s. But he was also an intellectual with striking insights into music and media and a talent for expressing those insights. He and the CBC were not only made for each other — each helped to make the other.

Gould himself was a writer and technical wizard as well as a performer. In the Canada of the 1950s and ’60s, we weren’t just thinking about media, music and new technology — we were talking about them. And Gould was one of the leaders of that conversation. For a seemingly reclusive guy, you couldn’t shut him up about classical music, northern Canada or the musicological brilliance of Petula Clark’s “Downtown.”

Contrapuntal voices

In radio/film documentaries like The Idea of North, Gould turned conversations into spoken contrapuntal music, using state-of-the-art recording techniques. If he were still alive (he’d be just 85 this year), he’d doubtless be scandalizing us with digital transformations of Bach and Adele.

Goddard knew Gould; they’d both studied at the “Con,” the Royal Conservatory, and both worked at the CBC. And while Gould seemed locked into classical music, Goddard, who understands both classical and popular music, sees him as a pop icon — “His blistering attack was pure jazz in its intensity” — and argues that his approach to recording was like that of Elvis Presley’s. Both “harnessed the full potential of playbacks and editing.” When we recover from the shock of such a comparison, we can see Glenn Gould was paving the way for the Beatles as well as for future classical pianists.

A scholar mocking scholarship

However brilliant a performer and articulate a musical educator, Gould had another Canadian trait: he didn’t take himself entirely seriously. Like CBC legend Max (“Rawhide”) Ferguson, Gould could create alternate personas, from pompous musical scholars to cab drivers, mocking his own talent and erudition.

Northrop Frye anticipated him in his major work, Anatomy of Criticism, which transformed literary criticism in the 1950s and ’60s. But “anatomy” was the term Frye used for a particular genre in which scholars mock scholarship itself. Gould must have understood that when he called one of his CBC TV shows “Anatomy of Fugue.”

Still, when we see Gould explaining music on YouTube, it’s striking to see an adult talking (mostly) seriously to other adults. He may mock himself, but never us. He doesn’t talk down to his audience, and he speaks in coherent sentences. Listening to today’s mumbling musicians trying to promote their careers on CBC’s q is, by comparison, a painful experience.

Goddard is aware that others have written full-fledged biographies of Gould; this account is part memoir and part cultural history. He mentions Gould’s oddities — the pills, the overcoats worn in summer, the fussiness over finding just the right piano — but he doesn’t obsess about them or try to seek some key to Gould’s personality in them.

Instead he shows us an extraordinary artist born in precisely the right time and country. The CBC provided him with a superb venue, and he made it an even better one by exploiting and developing the media technology of his time. He taught us all to understand music — if not at his level, then at least at a higher level than before — and to see and hear the world in surprising new ways.

We owe him a great deal for that, and we owe Peter Goddard for his informed, insightful, and well-researched insights into a great Canadian thinker. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: