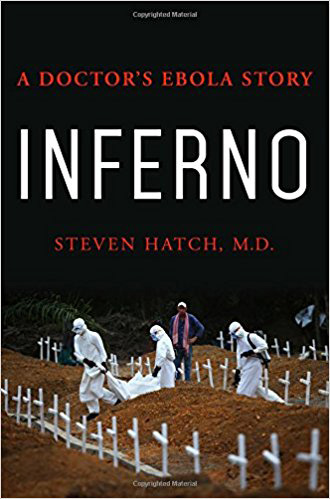

- Inferno: A Doctor’s Ebola Story

- St. Martin’s Press (2017)

Early in the 2013-2015 Ebola outbreak, blogging here in Vancouver, I was baffled by reports that a treatment centre run by Médecins Sans Frontières had been attacked by mobs of young men. Eight people on a team of health communicators were murdered by villagers who thought the outsiders were coming to spread Ebola, not to stop it. And even when West African funeral customs were known to be a key factor in the spread of the disease, people kept holding such funerals.

Such reports taught me that culture plays a major role in the spread or containment of a disease outbreak. West African culture is strongly skeptical of the value of government (both Liberia and Sierra Leone are just a few years out of horrible civil wars). That includes government-supported health care, which can’t do much in facilities like Liberia’s John F. Kennedy Medical Center. In West Africa, hospital is where you go to die, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: no one seeks help until it’s too late.

Western cultural attitudes, however, can be just as limiting. The World Health Organization didn’t respond to reports of an unidentified hemorrhagic disease until late March 2014, some three months after the first cases in eastern Guinea. Only in August was Ebola formally named as a “PHEIC”: a public health emergency of international concern.

Dr. Steven Hatch, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, also ran into cultural barriers when he tried to help fight Ebola. His new book is blunt, well written and honest about culture as a hazard to public health — not just West African culture, but ours as well.

Dr. Hatch had previous experience in Liberia, which inspired him to return to help out. But first he had to overcome the barriers his own culture put up. The outbreak received scant attention in the West until a couple of American doctors contracted Ebola in Liberia; in the West, no outbreak is really serious until westerners, especially Americans, get sick.

Leaving his academic position involved bureaucratic hassles, so it wasn’t until the summer of 2014 that Hatch finally got back to Liberia. His description of life and death in the Ebola treatment tents is vivid, detailed and horrifying. Treating patients involved getting into “PPE” — personal protective equipment that sealed him off from infection while turning him into a kind of alien monster to his patients. In sweltering humidity, his rubber boots filled with sweat.

“I wasn’t sure what to do,” Hatch writes. “... I did have a checklist of symptoms to review with [my patients], but it was written in a small font, and my glasses were fogged with sweat, and the goggles over the glasses were misty.... Only gradually did I realize I didn’t need the checklist because I could talk to the patients.”

But he couldn’t use a stethoscope; even looking at a patient was hard to do. Yet he had to examine his patients carefully because this outbreak was the first chance to do serious research on Ebola. Taking notes was almost impossible: the paper tore in the muggy air, and it couldn’t be removed from the tent anyway. (A colleague figured out a solution: take an iPad photo of each page at a safe distance from the tent.)

Hatch also saw that Liberia’s rudimentary health-care system had been effectively shut down by Ebola. Many Liberian doctors and nurses died caring for their patients. Patients avoided hospitals and clinics for all other health needs, from prenatal care to vaccinations to malaria. More Liberians died from other diseases during the outbreak than died from Ebola itself.

Even when he returned, Hatch found cultural problems. A Liberian had arrived in Texas and triggered a major outbreak of Ebolanoia — a contagious mental disease, with some state governors like New Jersey’s Chris Christie acting as superspreaders. Rather than being praised as heroes, returning health-care workers were being treated as plague carriers. Hatch tells us he’d never been afraid in Liberia, but the prospect of returning to the U.S. scared him badly.

Hatch’s own employer — a major medical school — panicked when it was learned Hatch had actually hugged a colleague when he came home. He got through that scare, and even arranged a return to Liberia when Ebola broke out again after being declared officially over.

While we like to think that Western medicine is far superior to others, Ebola taught us that medical anthropology must be a key item in our tool kit. If we don’t understand and respect the culture and values of other societies, our attempts to help them will only hurt.

And they will even hurt the caregivers like Hatch, who risk becoming as alien to their colleagues as they are to their West African patients. Fighting an outbreak is a lot like fighting a war, and the combatants — patients and caregivers alike — do not survive unscathed. Ebola survivors deal with stigma, depression, and a host of physical problems like vision and hearing loss. Their caregivers risk similar consequences, at least in terms of mental health.

Cultures are stubbornly resistant to change, and that’s especially true of medical cultures. Until the health-care systems of the West understand the cultural aspects of disease, they will fail to deal with future outbreaks of Ebola and other diseases. They will fail both their patients and the caregivers they’ve inadequately trained. Steven Hatch’s book is a step toward that understanding. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: