- The Politics of Fear: Médecins Sans Frontières and the West African Ebola Epidemic

- Oxford University Press (2017)

This book should be a required text in every school of public health in the world, and in the training program of every health-related nongovernmental organization. Health bureaucrats and journalists should have it on their phones and tablets, where they can consult it when new outbreaks occur.

That’s because it throws a new kind of light on a serious disease outbreak — and especially on how we respond to such outbreaks. Here, the real story is the failure of the global health community to understand its own considerable role in the spread of Ebola and other diseases.

After any bad outbreak, governments and nongovernmental agencies usually do private post-mortems and then issue bland “lessons learned” reports that may or may not be applied in the next outbreak. This post-mortem by Médecins Sans Frontières is neither private nor bland. It is a tough look at itself, involving both its own people who fought Ebola in West Africa and outsiders given access to MSF internal documents about the outbreak.

Then, rather than keep the findings in-house, MSF brought out this book. Of its many lessons, one stands out: health workers’ culture and politics are as much a part of an outbreak as those of the people they help, and fear drives both culture and politics.

The culture of MSF is one of independence, but as one of the contributors to this book admits, MSF can also be arrogant. It had extensive experience dealing with earlier Ebola outbreaks in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and it was already working in West Africa. So it led the response — and the response was too slow.

From a single case in a small village in eastern Guinea, Ebola had spread unnoticed for weeks via roads and cross-border forest paths. It reached big market towns and then capital cities like Guinea’s Conakry and Liberia’s Monrovia. Alarmed, MSF tried to alert the world but failed. The World Health Organization’s regional office for Africa is largely independent of the main office in Geneva, and it’s run by political appointees; it was slow to report to Geneva.

Geneva, in turn, was slow to respond. WHO didn’t want to hurt the economies of West Africa by sounding an alarm, or embarrass the governments of three fragile nations.

Worse yet, the politics and culture of the West are now locked into what contributor João Nunes calls “the securitization of issues hitherto kept outside the realm of security — that is, their framing as existential threats demanding exceptional security.” So the West would react to Ebola by treating it like a foreign invasion or a major terrorist threat. Even MSF, terrified by the plausible prospect of a million cases, called for the militarization of the Ebola response.

This would be the worst possible way to deal with the culture of West Africa, which already sees governments and their agents as the enemy. Liberia and Sierra Leone are still recovering from horrible civil wars, and Guinea is no democracy.

West African culture also venerates traditional healers, and has elaborate rituals for the dead: bathing the body, caressing it, and kissing it to show the love of family and friends. This was a fatal combination. One healer contracted Ebola from a patient. His own funeral led directly to about 350 additional Ebola cases.

A catalyst for fear

But West Africans have their own securitization worries: the western response to Ebola threatened their own health system and culture. Nunes cites Philip Alcabes, who argues that “disease functions as a catalyst of other fears in society — the fear of strangers, of technological development, of racial difference, and so on. The dread of disease is never just about a specific disease; it is also about the political fate of a society.”

So while West Africans threatened to wreck MSF Ebola clinics and Ebola patients fled those clinics, the rest of the world ignored the outbreak until it looked like a threat to them — especially after one sick Liberian got all the way to Dallas, Texas. He then entered a hospital that was no more ready to deal with him than the hospitals in Liberia, and two of his nurses contracted it from him. The American media freaked out, complicating the response.

And “response” itself is a cultural artifact. Nunes criticizes WHO for its “predominantly reactive nature”: “They responded to a problem already underway instead of working proactively to address the conditions that allow problems such as these to emerge.” That applies equally to Canada and the current threat of opioids.

MSF in West Africa was caught in a contradiction it is now trying to resolve: is it a “response actor” bringing help, or a proactive advocate for global health measures that will make help unnecessary?

MSF of course tries to be both, but it’s easier to count the lives saved and lost; advocacy makes you lobby governments that may ignore you. Another contributor, Adia Benton, points out that in an outbreak like Ebola, “the domestic military and police are mobilized against certain segments of the population in defence of elites and special interests.”

In Liberia, that meant soldiers shooting into an angry crowd in the Monrovia slum of West Point because the government wanted to seal off the whole slum. They killed a teenager named Shakie Kamara.

Such governments are all too common, and unable to “address the conditions” that lead to emerging diseases. Their people are poor, uneducated, malnourished and understandably suspicious of anything their governments impose on them — including health measures unrelated to the local culture.

As Benton observes, “A politics of fear now pervades the global health agenda.... The politics of fear has led to a short-termist agenda focused on crisis management and disease containment.”

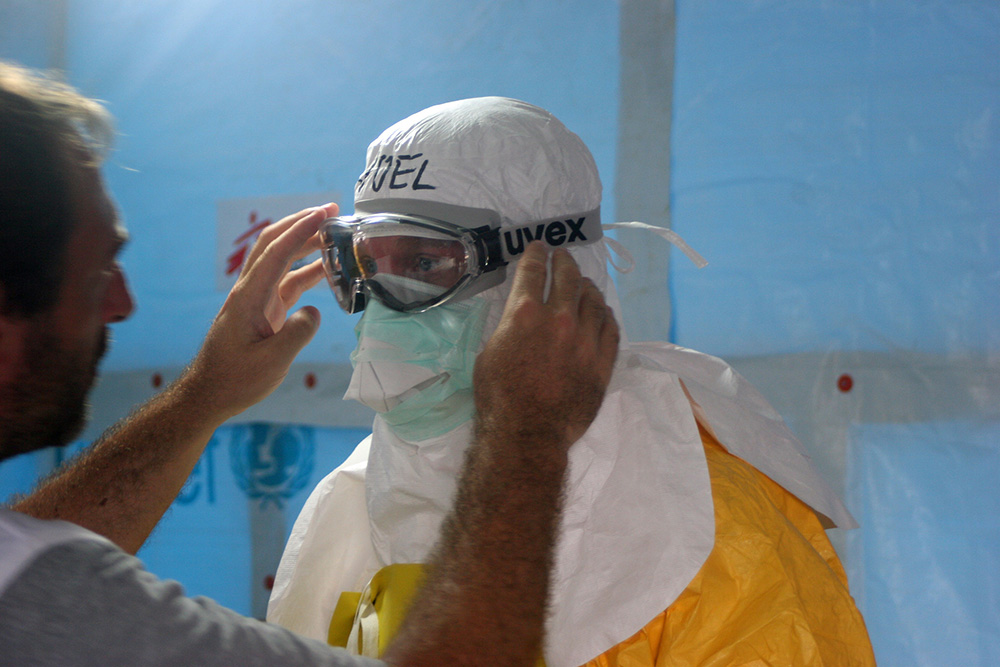

In the short term, of course, you’ve got to find the cases, trace their contacts, quarantine them, hospitalize them if need be, and bury them safely if they die. At every step, you’re facing bitter resistance from people who rely on friends and family, not on foreigners in space suits, who dread the stigma of disease, and who expect proper rites when they die.

It’s as pointless to blame the victims for their beliefs as to blame them for contracting the disease in the first place. Better, in the long term, to create a society where people are less likely to fall ill, and where they’ll trust their caregivers if they do get sick.

Having established such critical points in the first chapters, The Politics of Fear goes on to detail the brutal decisions to be made in the midst of an epidemic: How do you get people and supplies in, when most airlines have stopped flying to West Africa? How do you medevac western doctors who fall ill, and why don’t you medevac their African colleagues? Can you keep patients hydrated when you’re wearing a space suit and can barely handle a needle, and when more patients are waiting nearby for someone to die and free up a bed?

An ethical nightmare

MSF faced a grim decision when Dr. Sheik Humarr Khan, Sierra Leone’s greatest doctor, contracted Ebola while caring for his patients. He couldn’t be flown to Europe because WHO wouldn’t authorize it. But a couple of doses of ZMapp, a Canadian therapeutic never tried on humans but successful on nonhuman primates, were available from a Canadian laboratory team. Should Dr. Khan receive one?

The treatment team, from MSF and WHO, decided against it. Quite apart from the ethics of using an untested therapeutic, it was afraid of the consequences if Dr. Khan died anyway: MSF would be accused of treating an African colleague as a guinea pig. He wasn’t even advised of its availability, and soon died.

Such horrifying ethical and logistical nightmares are now built into every outbreak, while the dominant political culture of the West prefers to react to disease rather than prevent it.

After all, you know public health is working when nothing happens. No political advantage in that. But let some scary new disease break out, and you can send in the army, and that’s political gold.

The Politics of Fear outlines some of the key challenges facing the health community for the foreseeable future. Whether commandos like MSF, or the GPs in your walk-in clinic, health-care workers will contend with public health problems — and those problems will stem not from some virus or social ill like opioids, but from politicians’ decisions not to stamp out their causes. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: