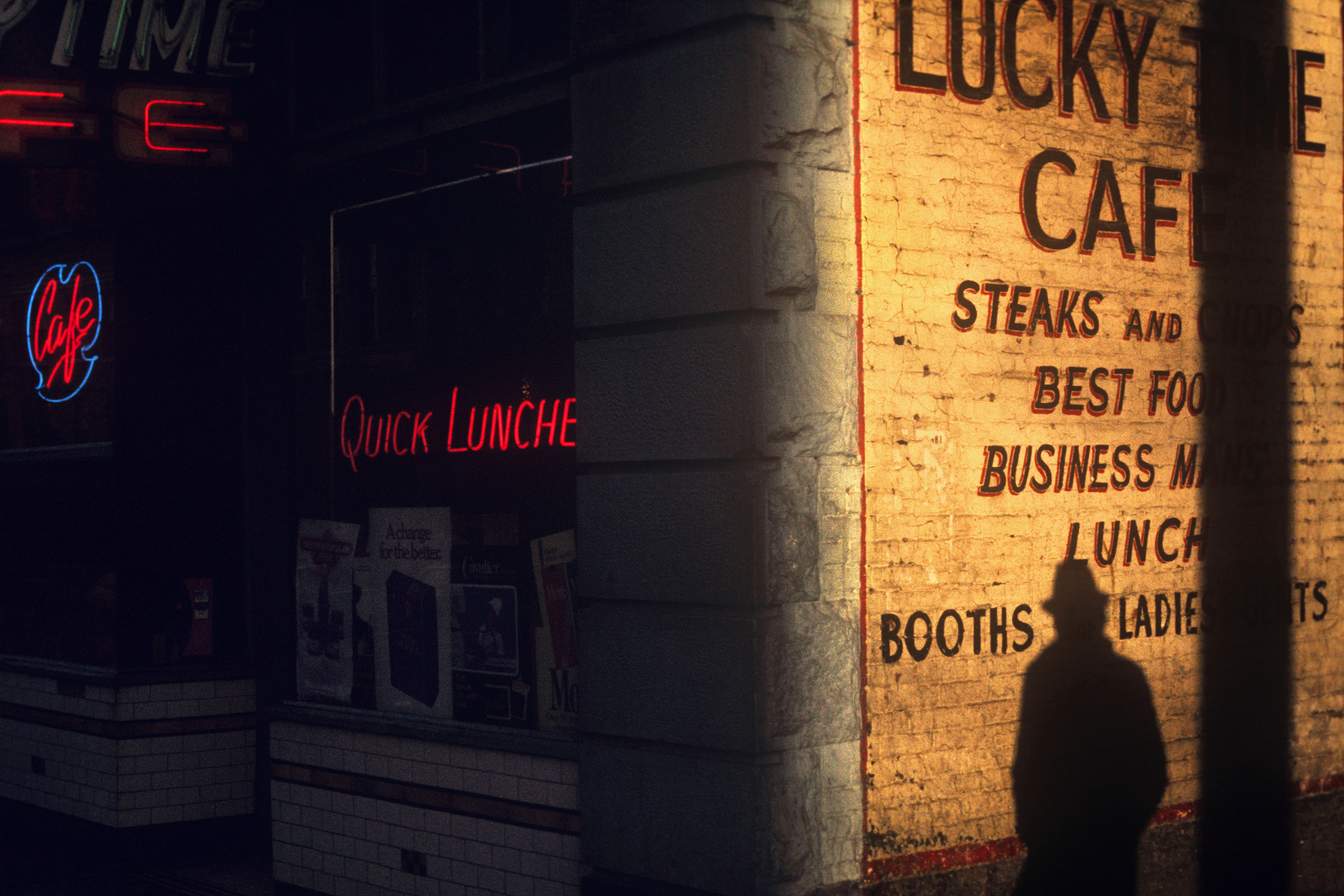

[Editor’s note: Before Greg Girard became a renowned photographer of Asia’s hyper-urbanization, he was a teenager busing from Burnaby to Vancouver, where he’d prowl the streets with his camera. This was Vancouver pre-globalized, pre-glitzified, Terminal City toughing it out on nature’s ragged edge. Girard felt drawn, as he says in the interview below, to “making pictures in somewhat unloved and orphaned places around the city” — many of them at night. His photos from that decade are collected in a new book, “Under Vancouver: 1972-1982,” which launches, with an exhibit, tomorrow, April 22, 2 to 4 p.m., at Monte Clark Gallery in Vancouver.]

David Campany: The oldest images in this book are from 1972. Clearly Vancouver has changed a lot, and large parts of the city would be unrecognizable to someone from the early ’70s. In going back so far, do you recognize the photographer who made these photographs?

Greg Girard: “The mental image of myself when I first started photographing remains pretty clear: taking the bus into town from the suburb where I grew up, walking the downtown streets, hanging out in pool halls and cafes, asking people if they would let me photograph them. This was the early 1970s, but some places looked like the ’50s or earlier — the way people dressed, certain interiors. I don’t know if time lags in the same way today. In Vancouver, it doesn’t seem to. Everything looks pretty much ‘now.’ The big difference is that ‘now’ is far more Chinese or south Asian than it was 40 years ago.

“Someone asked me if it was my early intention to document Vancouver. I don’t think I would have known what that meant at the time. At age 18 or 19, making pictures for posterity was the furthest thing from my mind. And during the 10 years that these pictures were made, that didn’t really change. What did change was my relationship with the city, and the gradual discovery that photography was a good way to separate how things look from how things are.”

Can you elaborate on the impulse to ‘separate how things look from how things are’? One might say that’s almost an anti-documentary impulse.

“I love that term ‘anti-documentary.’ I’m not sure how much it applies to me, though. It reminds me of the approach of certain Japanese photographers from the late 1960s and ’70s: a very subjective, highly stylized, almost novelistic way of picture making.

“A photograph can be about what’s photographed, but also about something more. The tension can come from that interplay between what’s photographed and the ‘something more’ (even though it might not always be intended by the photographer). Sometimes appearances don’t always align with what you know or suspect to be true. Photography seems able to show the surface and peel it back at the same time.

“It’s probably also worth noting that a 10-year span for a young photographer (aged 18 to 28) is a long time. I started out hardly knowing how to frame or expose a photograph, but I eventually got the hang of it, and over time tried to develop something of my own. By the time I left Vancouver in 1982, I’d learned a lot about long exposures at night and what various artificial light sources did on different kinds of film.

“Kingsley Amis wrote that he ‘drinks to make people interesting.’ I worry that photography can be a similar intoxicant; photographing the world to make it interesting.”

Why is that a worry? It seems as good a reason as any. Were you finding the world less than interesting at that time? Was photography a way out of something?

“I understand Amis to have meant a relaxing of discernment. If everybody is interesting, then nobody is interesting. And so it goes with the world.

“My view of Vancouver went through a lot of changes: discovering it as a ‘big’ city when I was young, and then returning to it later after having lived abroad and seeing it in relation to a wider world. At some early point, photography became a way to engage with the world, or make it my own, so to speak. And so, you’re right that photography was a way out of something, but also into something.”

Looking at the pictures now, are you able to see, or recall, what it was that motivated each one? Photographs have a way of masking the intentions that brought them into being. If, as they say, the past is a foreign country, then a photograph can be doubly foreign.

“There was never any intention during this time to make pictures about Vancouver per se. It was where I lived and so that’s where I made pictures. I was probably trying to avoid anything that looked too obviously ‘Vancouver’ in later pictures — hence the anonymous alleys and streets and could-be-anywhere buildings and cars. Which is odd now, because when viewed from the distance of today, they all look quite specifically ‘Vancouver’ to me.”

“As for motivation, especially early on, much of it was strictly physical, if that’s the right word: the way the light was hitting something or someone; the way a person or a building or a street looked. The drama of that. At the same time, the way things looked connected on some level with the way I felt about Vancouver and my place in it. By the end of this period, I was ready to leave, though why I felt that way I can’t really say. But the pictures maybe reflect something of that.

“Looking at these early Vancouver pictures now, there’s something unguarded and direct about them. I had no idea at the time that they would ever be seen, or that I would ever figure out how to have some sort of life as a photographer. But beginnings are like that, I suppose. You have no idea what you’re doing, and you just plunge ahead, trying to distill everything around you and within you, while avoiding thinking too much about the seeming impossibility of it going anywhere.”

That’s interesting. Early work in photography can be pretty fully-formed, because the medium allows it. It’s not like having to learn to play the violin. And photographs can be fully-formed even if the photographer isn’t. Maybe that’s something unique to the medium.

“I might argue that technical expertise and virtuosity still has its place, though the bar for the medium today is comparatively low. Does that make it more like writing, I wonder? In the sense that even if someone can read and write, it doesn’t mean they are a writer. I’m not really a musical person but maybe an early body of work is like an early rock ’n’ roll album — something you can only do when you’re young.”

Yes, I think photography can be like writing in some ways, and not others. I often think about that comparison between early photography and early rock ’n’ roll albums. But if great things can be done so young, what is the mature work of a photographer? Is there such a thing? Can we discern it?

“I wonder if it helps to look at the work of someone who enjoyed little or no recognition during their lifetime. Vivian Maier is an example that leaps to mind, and Fred Herzog, too, in the sense of the late acknowledgement of his work.”

Maier and Herzog seemed fully formed at an early stage in their work, but maybe it’s the disposition toward the world as subject matter that can be mature so early, and the photography more or less follows from that. You mentioned there being a place for virtuosity, and I’d certainly agree. But there is such a thing as virtuoso observation — a photographer who sees the potential significance of an overlooked subject matter, for example, like Walker Evans. Or a photographer like Garry Winogrand, who, in a physiological sense, was able to see so much so quickly.

What’s virtuoso in photography is complicated, because it’s so bound with vision, seeing, recognition. I have the impression these early pictures of yours are a mix. Some are quite raw and direct, and their technical qualities needed to be no more than competent. In others, you’re beginning to explore what a photograph can be as a picture.

“With Winogrand, there’s certainly an element of the physiological as you describe it: not only acute observation but divination almost, matched with a technical virtuosity — of the kind more typically seen in news or sports photography — which he applied to collisions and alignments within the everyday that don’t exist until you photograph them. As for my own work, I felt I was getting into uncharted territory with the night pictures — finding out what the medium could do at night, especially when no obvious light source was visible in the frame — and in making pictures in somewhat unloved and orphaned places around the city.

There’s a kind of alone-ness — I hesitate to call it loneliness — in a lot of your Vancouver photographs. Scenes with just one human figure or none at all. Is this to do with disposition — the young, wandering outsider, seeking subject matter that mirrors his inner state? Or did you feel Vancouver was like that?

“I did feel Vancouver was a sad town. It maybe had something to do with the way the natural beauty surrounding the city was at odds with the more down-at-the-heel parts of town where I was spending time. In those days, Vancouver was more obviously a port town, the last stop at the end of the rail line. ‘Terminal City’ as they say, a place where people ended up. Something that most port cities probably have in common. When Nina Simone did her rendition of ‘Baltimore,’ singing about a ‘hard town by the sea’ where it was ‘hard just to live,’ I felt she was singing about the place I was living. Which might sound odd, considering the Vancouver of today. It would be like a mournful song about Aspen or Honolulu. Though why not? The prettiest places can be the most ruthless.”

Were you working in isolation? Did you have connections with other photographers or artists at this time? And what did you know about photography’s past? Had you seen books or exhibitions?

“I didn’t feel like I was working in isolation. There was a lot to be stimulated by, whether at home or abroad. But, during this decade (1972 to 1982), apart from a few close friends, nobody saw the pictures.

“The earliest photographs I saw presented as ‘photography’ were in magazines like Popular Photography or Modern Photography, and later in Camera Asahi and Camera Mainichi, in Tokyo. Interspersed with camera ads and tech tips would be portfolios by Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Harry Callahan, Duane Michals, Ralph Gibson, and others, lesser known now perhaps: Marie Cosindas, Ikkō Narahara, Eva Rubinstein. I gradually became aware of the history of photography. Not in any systematic way, but over time, I started to see how some of the pieces fit together.

“I lived in Tokyo from ’76 to ’77 and from ’79 to ’80. Photography was a huge part of the cultural landscape: magazines and books and exhibitions; and in advertising: posters in train and subway stations, billboards. One intriguing image/idea after another. The camera manufacturers all had their own galleries, in Ginza or Shinjuku: Nikon Salon, Canon Salon, Minolta Salon, Fuji Salon, and others, like Zeit Photo Salon. (I remember them all as “salons”; some perhaps were “galleries.”) This is where I saw my first photography exhibitions. Some were great, some were of the “camera-club” variety. But the main point is that you didn’t have go to a gallery to see great photography in Japan.

“Shortly before leaving Vancouver again, in 1982, for what turned out to be an almost 30-year period in Asia, I met Vancouver artist Roy Arden, who became a close friend and ally. I kept in touch with him while I was away and followed the evolution of his career and the trajectory of the city, this other Vancouver, one where artists were living and working and gaining attention, as was the city itself.”

Your early Vancouver photographs responded to the presence of various Asian cultures in the city. Was this a result of you having been to Japan in the late 1970s or were these images made before that?

“I think most people were alert to ‘things Chinese’ in Vancouver back then. Classmates in school, Chinese-owned shops and businesses and farms, and the city’s sizeable and very alive Chinatown — probably that all played a part in why I ended up going to Hong Kong in 1974, travelling in that part of the world, becoming curious about Japan and living there in the late 1970s. Yes, after those first visits to Hong Kong and extended stays in Tokyo, I became more attuned to places in Vancouver where that part of the world might show itself: Japanese magazines at Sophia Bookstore, cargo ships on the waterfront, ESL students on Robson Street, and Chinatown a place to get your bearings.”

Nothing dates quite like an automobile. Can you say a little about the prominent place they have in this work?

“The cars might look appealingly retro today, but at the time, they were just beat-up cars that had yet to cross the threshold of retro appeal. I’ll admit to being attracted to their unloveliness, though. The unnatural colour from artificial light and the darker sky made them stand out in a way they wouldn’t have during the day. Which is all to say that the cars perhaps served as a kind of visual shorthand for appreciating the unappreciated, noticing the unnoticed.”

You began making these images the year after Walker Evans had a career retrospective at MoMA, which travelled to Ottawa, but not Vancouver. In the catalogue and press release for that show, the curator John Szarkowski famously wrote: ‘It is difficult to know now with certainty whether Evans recorded the America of his youth or invented it. Beyond doubt the accepted myth of our recent past is in some measure the creation of this photographer, whose work has persuaded us of the validity of a new set of clues and symbols, bearing on the question of who we are. Whether that work and its judgment was fact or artifice, or half of each, it is now part of our history.’ Are you able to say whether you were recording the Vancouver of your youth or inventing it? Or is the uncertainty now part of your, and Vancouver’s, history?

“When I started making these photographs, especially the pictures of people in the mid-1970s, I felt like I was photographing a world nobody knew anything about, apart from the people living it, of course. I was something of an interloper, but my youth protected me. It’s curious to consider these pictures now, practically unseen since they were made, in terms of a Vancouver they might have some potential to invent. Other visual records of Vancouver from this period, whether in newspapers or elsewhere, look quite different to me from the one I lived in and photographed. I sometimes wonder if there might have been another 20-something roaming the streets and photographing at night back then. (And if so I would love to meet him or her.)

“It’s said that all photographs are interesting after 20 years. That notion wouldn’t have meant much to me at the time. All I cared about was seeing how good the pictures were when I picked the film up from the lab. I don’t know if the Vancouver in these pictures is invented or not, but I do recognize it as the one I was trying to photograph.” ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: