Could Singapore, a city-state of 5.5 million people across the ocean in Asia, hold the key to B.C.’s housing future?

On a recent trade mission to Asia, Premier David Eby was introduced to Singapore and its successes in providing affordable housing for its citizens. With a promised BC Builds program in development, Singapore shows what a public sector that was more engaged in the development of new affordable housing stock could look like.

Let’s take a deeper look at the Singapore model and how it has evolved over six decades. I also visited Singapore earlier this year (separately from the premier) and got to see some of the city’s housing handiwork firsthand. One of my cousins, a corporate lawyer, was keen to show me some of the public housing built in Singapore, with many impressive developments that look a lot like high-end condos in Vancouver. Prices in the resale market, he added, also look a lot like Vancouver.

Singapore shows how quickly progress can be made on affordability through a large public building program, but with a twist, as it has largely been providing affordable home ownership units.

Singapore’s housing market is also much more tightly regulated and managed than in B.C. (or anywhere else in North America) to extents that may be impossible politically to replicate. Singapore’s public flats have become a vehicle for private wealth accumulation, and alongside it speculative behaviour and a political imperative to protect people’s nest eggs.

Singapore housing by the numbers

Singapore’s economic success is arguably built on a foundation of affordable housing for its citizens. Some public housing and development had previously occurred under a 1927 (British colonial era) Singapore Improvement Trust. An independent Singapore in 1960 created the Housing and Development Board to build rental units at a time of housing crisis.

After the immediate crisis was abated, housing policy shifted to promote home ownership over renting, and for more than two decades (1982-2006) the Housing and Development Board stopped building rental units altogether. Today, ownership accounts for 94 per cent of the HDB stock.

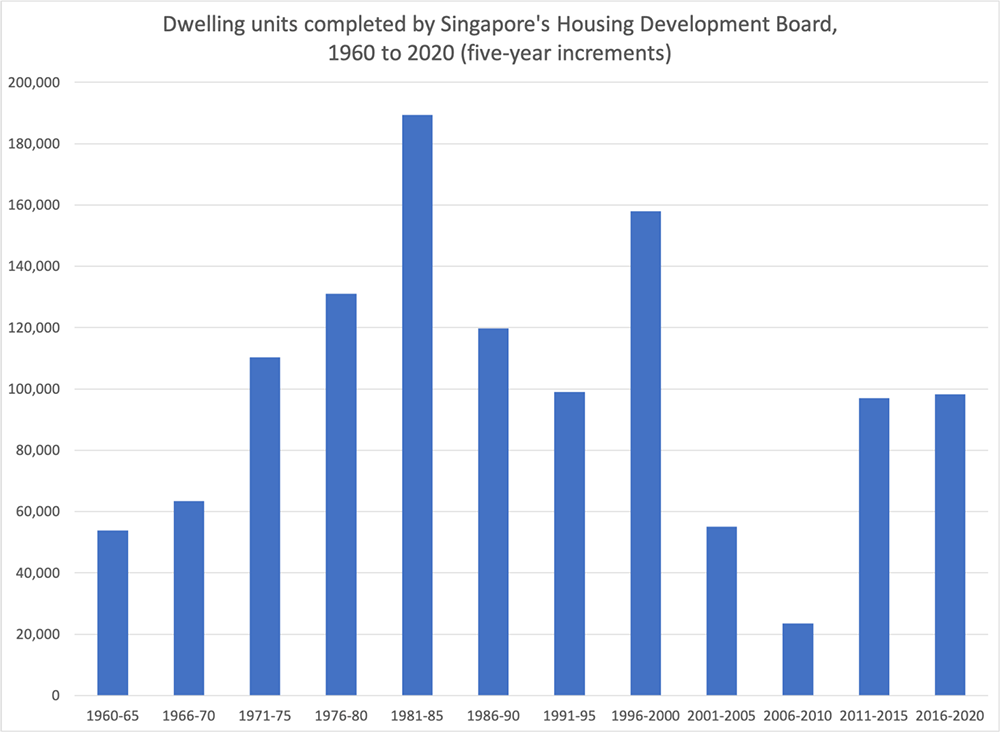

Starting in 1960, the Housing and Development Board built 21,000 flats in its first three years, and 121,000 within a decade. By 1970, 35 per cent of residents lived in public housing and 70 per cent by 1980, up from nine per cent in 1959.

Construction of new units held steady over the decades, and from 2011 to 2020 almost 20,000 units per year were completed.

As of 2021-22, cumulative development by the Housing and Development Board has exceeded one million units, housing 80 per cent of Singapore residents (as noted below, Singapore also has a large non-resident population).

Just as impressive as this growth are the prices for new flats. In 2021-22, typical prices for a one-bedroom unit ranged from $95,000 to $234,000, and for a four-bedroom from $372,000 to $525,000. In addition, a housing grant of up to $80,000 is available to first-time home buyers earning less than $9,000 per month ($108,000 per year). Prices in the resale market can be much higher.

Singapore has integrated Housing and Development Board development with its excellent public transit system and the development of complete communities. The city is divided into 24 towns and three estates "designed to be self-sufficient, with easy access to shops, schools and social and recreational facilities, and an abundance of greenery.”

Housing and Development Board development includes commercial properties, including over 13,000 shops, more than 1,000 restaurants and food stalls, and other community facilities, including more than 1,000 child-care centres and health and social services facilities. Some 10 to 15 per cent of land in a development is allocated to light industry to tap the pool of nearby workers.

How the Singapore model works

The major emphasis of Singapore housing policy has been on ensuring home ownership for middle-class families. New Housing and Development Board flats can only be sold to Singapore citizens, and a series of priority schemes is used to allocate new units.

Up to 95 per cent of flat sales are set aside for first-time applicants, including special priority for young couples. People wishing to live close to their parents get additional weight in the selection process.

In addition to the housing grant noted above, a number of other incentives and subsidies exist to facilitate home ownership, including allowing prospective buyers to tap savings in Singapore’s mandatory retirement plan, the Central Provident Fund, towards their down payment.

The CPF and Housing and Development Board are tightly integrated in a closed-loop model of housing finance: the HDB holds the mortgage instead of a commercial bank, and the CPF directly pays the HDB out of the owner’s CPF ongoing savings.

Importantly, Housing and Development Board developments are mostly 99-year leases, with land perpetually owned by the government. This is similar to community land trusts or leasehold properties in B.C., for which units are cheaper to purchase. In addition, targeted programs for elderly citizens allow them to purchase a flat on flexible shorter-term leases to make them more affordable.

Land acquisition for redevelopment was a key function of the Housing and Development Board starting in 1966 (after the first wave of building to address the crisis). The Singapore government was concerned about land prices rising due to public investments and wanted to avoid windfall profits going to existing landowners. Its land acquisition program gave the government broad powers to acquire land and allowed the government to pay compensation for land at prevailing market value (prior to increases in density to allow apartment buildings).

To address displacement, the redevelopment process was accompanied by the provision of alternative accommodation for impacted households and businesses.

Housing and Development Board flats must be held for a minimum of five years before resale, and the various financial incentives are not available for second purchases. Permanent residents can purchase flats on the resale market, but there are some restrictions in the name of ethnic diversity that limit resales.

In the early decades, Housing and Development Board projects focused on basic designs for buildings and units in order to keep costs low and complete construction quickly. But these have become more sophisticated with design aesthetics and amenities synonymous with higher-end properties, including “executive” units aimed at more affluent households. The Housing and Development Board has also been actively upgrading its older housing stock.

To counter Singapore’s early history of racial segregation, the government has implemented a policy-driven effort to use housing towards integration. A United Nations report notes that Housing and Development Board neighbourhoods “are characterized by social and economic heterogeneity, as the policy of the HDB (via its allocation policy and in planning for flats of different sizes within the same precinct) was aimed at ethnic and social class integration.”

Challenges with the Singapore model

Singapore’s housing model has benefited a large share of the population, many of whom now own housing assets that have increased in value substantially since purchase. The government must thus guard politically against a drop in prices as it builds new housing.

In the 1990s, a policy of “asset enhancement” was a political vote getter. As prices have increased, policy has shifted towards targeted subsidies for new buyers rather than measures to lower the cost of new housing, which keeps valuations high for incumbent owners.

A consequence of high prices relative to incomes is that for some households, a significant part of CPF savings is used for the down payment and continuing mortgage payments, leaving much less for actual retirement. While they hold a housing asset, the 99-year lease means it will reduce in value over time with older apartments now halfway through this process after which land reverts back to the government for redevelopment.

The Singapore government has been actively tinkering with its housing policy on both the supply and demand sides of the market based on demographic trends (an aging population), and shifts in the business cycle. Rather than build in advance of demand, the HDB has shifted to a “build to order” model similar to condo developments in North America, where construction begins only after 70 per cent of the units have been pre-sold. This adds to delays for acquiring new housing (three- to five-year waits) and keeps resale prices high.

As noted by Chua Beng Huat of the National University of Singapore, public flats become a vehicle for private wealth accumulation. A push by the Housing and Development Board to higher-end housing has been accompanied by speculative behaviour, with some buyers of HDB flats seeking to sell after the minimum five years, pocket the windfall capital gains and purchase another property in the private market. Singapore residents comment on the growing number of sales of million-dollar-plus HDB flats in the resale market.

The Housing and Development Board stock includes some rental housing for low-income households, more than 63,000 rental flats (about six per cent of units). By design, most of the rental flats are studios and one-bedrooms, whereas ownership units are primarily two to four bedrooms. A complex set of rules and regulations govern who can apply for rental housing units, which have a six- to nine-month waiting list. Rents are progressively higher as incomes increase.

Singapore relies extensively on low-paid temporary workers, mostly from South Asia, to build new housing cheaply. These workers are hired on two- to three-year terms, cannot become permanent residents or citizens and live in crowded dormitories.

These workers constitute about four per cent of the population and are a subset of some 27 per cent of the population who are non-residents that add to housing pressures but who do not benefit from Housing and Development Board schemes.

In addition to the various regulatory restrictions described above, Singapore actively shapes demand through property transfer taxes called stamp taxes to quell speculative investment beyond one’s principal residence. No tax is payable for a Singapore citizen’s first property, but the rate jumps to 20 per cent of assessed value for the second and 30 per cent for third and subsequent properties.

Since 2005, private developers have been enabled to build public housing through a “design, build and sell scheme” as long as they meet the basic principles and features of public housing. Housing developers pay 40 per cent tax on purchases, but most of this can be avoided by meeting certain conditions.

Outside of the Housing and Development Board, there is a luxury market where foreigners can purchase properties built by private developers. Foreigners pay a flat 60-per-cent stamp duty on any purchases and corporate entities pay 65 per cent.

Could it be done here?

Altogether, Singapore holds important lessons for what a large public program aimed at affordable rental and ownership housing could look like: building at scale, acquiring land, planning housing to shape complete communities, achieving high levels of racial integration. Singapore shows that substantial public support towards building affordable housing can achieve big results in a relatively short amount of time.

A novel dimension of the Singapore model is aimed at affordable home ownership on leasehold land. B.C.’s culture of home ownership may thus be a good fit for a Singapore-style model, although a major buildout of affordable rental housing is still very much needed in the short-to-medium term given the existing crisis. And, not all renters want to be owners even if they could afford it.

A Singapore-style approach would undoubtedly be a radical departure from B.C.’s housing status quo, where 95 per cent of housing is market-driven. That said, the provincial and federal governments were both more active in this arena in the 1960s to 1980s, the legacy of which is in co-ops and non-profit housing around B.C.

Housing and Development Board developments, however, were built out while the city-state was in a much earlier stage of development than modern B.C., and Singapore is also substantially smaller in size at 728 square kilometres, compared to 812 square kilometres for the cities of Vancouver, Burnaby, Richmond, Coquitlam and Surrey combined.

A more profound challenge is that Singapore is a less democratic (and more conservative) society than B.C., and the very detailed regulations and restrictions of the Singapore model would be more politically contentious on this side of the Pacific.

But as B.C. contemplates more direct interventions into building new affordable housing in a context of energy transition and growing inequality, there is plenty to learn from the Singapore model. ![]()

Read more: BC Politics, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: