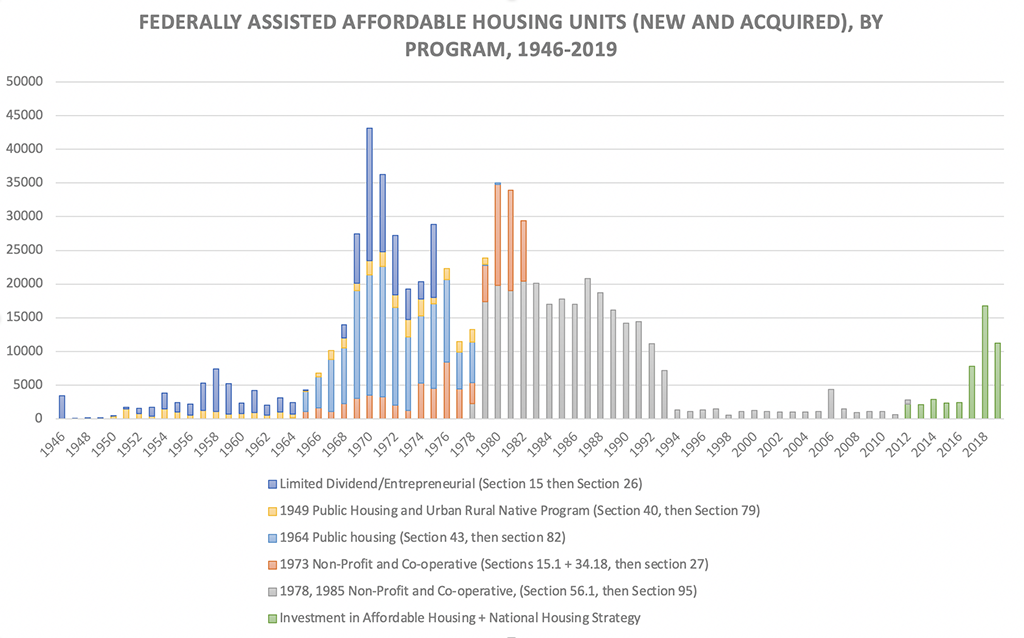

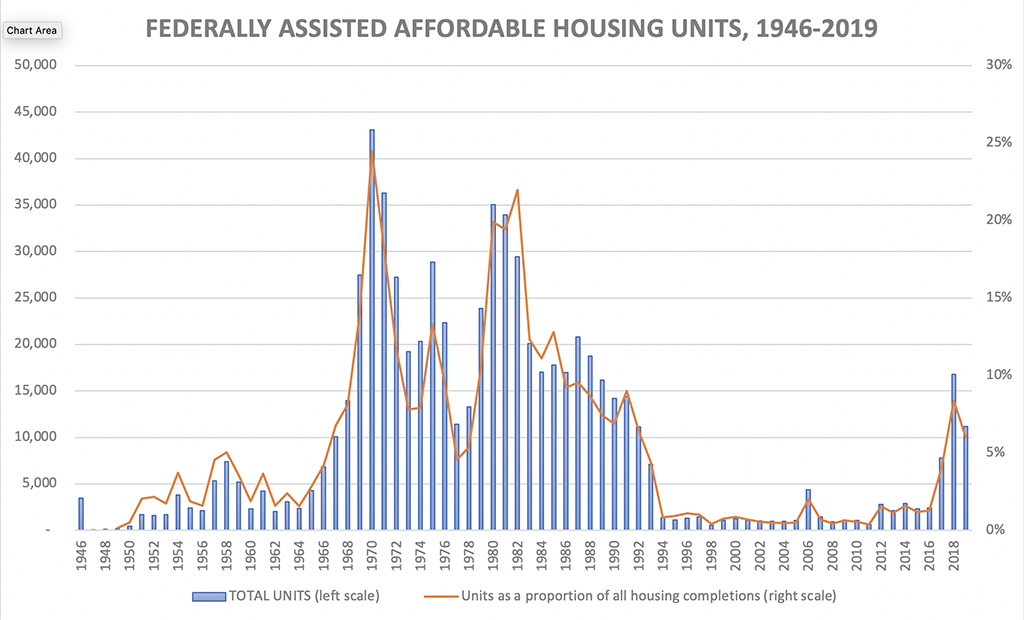

Between 1973 and 1994, Canada built or acquired around 16,000 non-profit or co-operative homes every year.

Between 1994 and 2016, that number dropped to just 1,500 homes a year, thanks to a decision made by the federal Liberals to get out of funding affordable housing. Instead, the responsibility was downloaded to the provinces, with mixed results.

After over two decades of rising home prices and growing homelessness, in 2017 the federal government finally announced it was getting back into housing, promising to spend $40 billion over the next decade.

But the pace of building is underwhelming, compared to what was done in the past. In the latest federal budget, the government promised 16,300 affordable homes over the next five years.

“That figure is essentially what we used to do in one year,” said Brian Clifford, a program manager at the Community Housing Transformation Centre.

Using historical data from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp., Clifford shows how much federal money Canada used to spend, compared with an abrupt policy shift in the mid-1990s that emphasized individual homeownership instead of funding affordable housing.

Before the ‘70s and ‘80s non-profit and co-op housing boom, Canada’s historic affordable housing stock also included 205,000 units of public housing developed between 1964 and 1978.

Then there were various incentive programs to build rental apartment buildings: between 1975 and 1984, the Canada Rental Supply encouraged the construction of 382,000 units. In the 1980s, that shifted too, as incentive programs ended and developers turned to building more lucrative condo projects.

The picture that emerges is stunning: even Brian Mulroney’s 1980s Conservative government — the era of free market enthusiasts Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher — spent more on affordable housing than the 1990s Liberals, headed by Jean Chrétien.

Today, the decision to turn off the taps for new affordable housing looks like a disastrous move. Affordable housing waitlists are long, and people can no longer afford to move out of social housing and into the private rental market. Thousands of people in British Columbia are homeless, a problem that affects small towns as well as big cities. Rents have skyrocketed, and elderly tenants fear that if they’re evicted, they won’t be able to afford another apartment.

To Clifford, the numbers say one thing: the federal government has to spend more — much more — to build and acquire affordable housing. While the National Housing Strategy has been heralded as a welcome first step in the federal government’s return to housing, many experts have said the amount of federal funding being devoted to the problem falls far short.

“What this indicates to me is that we've normalized neoliberalism,” Clifford said, referring to the term for a political ideology that emphasizes reducing government spending, deregulation and relying on free-market capitalism. “It’s been totally incorporated into the body politic.”

Although Mulroney’s Conservative government still spent on housing, Clifford said it’s important to understand the changes the Conservatives made to housing programs in the 1980s. Instead of continuing to fund mixed-income projects like housing co-ops, the government reformed housing programs to target lower-income people.

“This is a problem later on down the road, where you see that a lot of… [these buildings] are in trouble because the rents are not sufficient to cover the cost of maintaining the building,” Clifford said.

“And you see that the mixed-income buildings built under the program from 1973 to the mid-‘80s, those have been those that fared much better in subsequent years.”

Starting in the 1990s, a new affordable housing strategy was adopted, Clifford says: “The big players like CMHC, the big banks and the real estate sector — they developed a new affordable housing policy, which essentially facilitated individuals to get cheap mortgages to purchase homes and to facilitate wider homeownership.”

After several decades of dramatically underfunding affordable housing while encouraging cheap credit and incentive programs for homeownership, Canada’s current high housing prices and long affordable housing waitlists are entirely predictable, Clifford said.

It’s not like the federal government can just turn the clock back to 1974 — for instance, land prices are so much higher now compared to the decades when co-ops were being built across East Vancouver and Burnaby.

“If you could go back, you would require just billions and billions of dollars of investment to really make up for the kind of unit counts as well,” Clifford said.

Where should the federal government go to find extra money for new affordable housing? A good place to start is taxing profits made by real estate investors, Clifford said. He said the federal government’s plan to review housing as an asset class, announced in the 2022 budget, is a good idea. The review will include “potential changes to the tax treatment of large corporate players that invest in residential real estate,” according to the budget.

The budget also proposes taxing profits from property flipping “more fully and fairly.”

Clifford hopes his research will illustrate the huge gap that will remain between what Canada used to fund, the deep hole that was created when the federal government left the sector, and what’s needed now.

But Canadians don’t just need to rely on the government to fund the housing we need, Clifford said.

“What's also important is activism. The development of programs of a comprehensive housing policy based on a Scandinavian model which we were moving to in the early 1970s — that was the result of a lot of hard work, a lot of advocacy from a community groups from civil society,” he said.

“I think that the pressure is starting to be kind of turned on now. But what I would want to come out of this is the wider understanding of what we used to do, and how what we're doing now is totally inefficient. I would hope that the government response is going to be stepping up to respond to the crisis in proportion to what it is.” ![]()

Read more: Federal Politics, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: