If there is one positive shift which we should carry with us beyond this pandemic, it’s job flexibility. Employees found many benefits in doing at least part of their job from home.

We should be able to say the same for remote schooling, right? The parallels between work and school seem so obvious.

But what we have been hearing instead is that online learning has caused “irreparable harms” that will stay with students for years. When Ontario public schools returned temporarily to remote learning as the Omicron variant surged in January 2022, news coverage showed frustrated parents expressing how “devastating” the shift to remote learning was for them.

At the online learning centre where I teach on the Sunshine Coast, we transitioned to remote learning when COVID-19 hit, then back to having teachers available to meet face-to-face when things settled down, with barely a hiccup.

It was as far as anyone could imagine from the “devastation” and “irreparable harm” described by those critical of temporary remote learning as a pandemic safety measure.

And while most families get glimpses of the failings of the school system from time to time, it’s my daily reality.

I have been teaching full time at an online school for a decade. Before that, I taught for years in both mainstream high schools and alternative school programs.

I see students with anxiety and depression, those who are bullied and those who are figuring out their sexual orientation, those who are not being challenged, those who can’t keep up with the academic train that just keeps on rolling, and those who just don’t fit in — for many of these reasons as well as a variety of others.

Connecting with students “who just don’t fit in” has become my specialty.

Sometimes this involves working with students through the life-altering transition of leaving their regular school for an online learning environment. Some of my students have, upon discovering the option of online learning, decided never to go back to the classroom. Others have found a handy set of online tools they can reach for when needed, while also engaging with in-person learning when it makes sense for them.

So when the pandemic started, my students, who were already used to online learning, kept going as though little had changed.

‘When you are 16, you just want to be with people’

I spoke with a colleague of mine, Geoff Davis, who teaches humanities at Chatelech Secondary in Sechelt, just up the hill from the online learning centre where I work. His pivot to remote learning in March 2020 was different from mine.

“It was disheartening, those three months teaching from home,” he said.

He told me that his students with part-time jobs threw themselves into work. “Their job at IGA was 1,000 times more important to them” than any assignments he could pitch over Google Classroom.

What struck me is that employers were getting something right that schools weren’t. We often tell students that once they “get out into the real world” things won’t be so easy. There will be consequences if they don’t do their jobs or don’t show up altogether.

Perhaps school could be more like the real world where everyone has to do their bit for the team to move forward, where each person’s participation actually matters to everyone else.

Once students realized that his assignments weren’t required, that they would pass their classes no matter what they did for the rest of the year, there was little he could do to pull them in as a group. “My overwhelming sensation was of losing my students,” he said.

He related that all of his colleagues were struggling with “Our sense of not mattering and not wanting to admit how few of our students we were connecting with.”

It was also a horrible time for students without jobs, Davis said. “They were sinking into video-game land, and withdrawing and shrinking and not able to be alive in the world.”

If there was anything positive that he took away from the remote-learning experience, it was the value of face-to-face teaching.

“When you are 16, you just want to be with people. There is something that can’t be done online that can be done face-to-face.”

Effective online learning is here, if you want it

Valerie Irvine, a University of Victoria professor in educational technology, has a different take. She runs undergraduate classes for teachers in training and graduate programs for teachers. She is also the mother to two teenagers, so she saw the pivot to remote learning from more than one angle.

She isn’t surprised that teachers wanted to rush back to classroom-only learning in such a hurry, when their only remote-learning experience was a quick pivot to “crappy Google Classroom online teaching.”

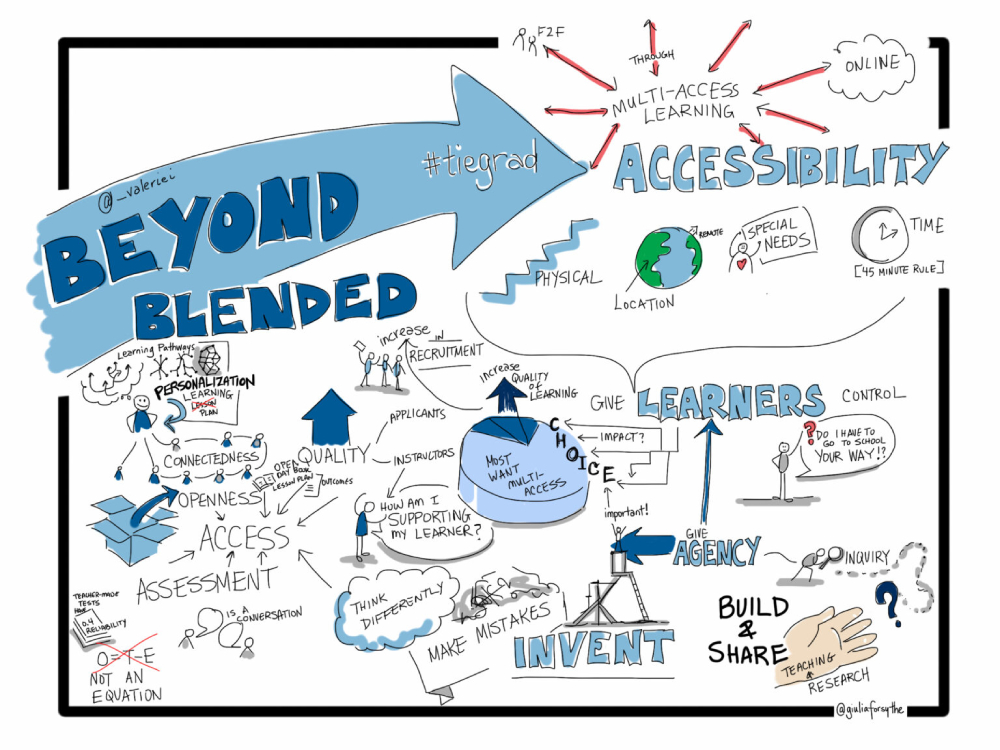

Irvine’s areas of expertise include multi-access and online teaching and learning. She explained her method for designing courses so that students can participate in-person or online, and can choose, depending on their circumstances, to slide effortlessly between modalities.

“We have to design for student community, student voice and student ownership of data for it to work,” Irvine explained.

Her self-described “recipe” for multi-access courses is to divide them into equal parts of whole-group instruction, teamwork in small groups and access to resources on the course website which students can work on individually but with support of their small group or the class as a whole. “There is no requirement to engage as it is all natural. They want to. It is a really authentic community that builds.”

She admits that this “Can’t be done with one teacher expecting to balance all of this with a normal face-to-face class. It is shifting the design; it is shifting the roles, but honestly, it is not hard. This will retain learners.”

A key piece of software that she uses is Mattermost, an open-source tool which operates like Slack or Microsoft Teams and which her students say is the best component of any course that they have ever taken.

“They make deep friendships and they attribute much of it to Mattermost and the small group meetups,” Irvine said. What this software does is allow them to create private channels. “It gives students power and voice and a chance to know each other.”

She also has students create blogs using WordPress, which, she tells me, is “Installed in many school districts, but they haven’t figured out how to turn the lights on. We create learner blog templates and teach them how to subscribe to each other.”

What each student gets, she explains, is something like a social media feed, but of their classmates’ learning. This teaches genuine digital literacy, she tells me. “The more you use things like Google Classroom, you kill digital literacy. Plus, there is no glue holding them together as a cohort.”

One of the issues that she has with learning management systems used in both online schools and during the pivot to remote learning is that once the course is over, the teacher shuts the whole thing down. “You break up the community that you just brought together and students lose access to all of the resources.”

She relates to me that she has had students come to her two years after she taught them still referring to “our class” as a thriving network of peers who continue to help one another out.

For each course, she runs “assessment meetings” which are fundamental to her teaching approach. Each student books in to see her, either in-person or over video-link, for both midterm and final assessments. “When we meet, we go over the learning,” she said. “It is a conversation.”

Any district could be running their schools multi-access from K-12, she tells me, but there is resistance since it represents a shift from the way that things have been done. “There is no reason any school district could not fully be there within five years. But it needs leadership actually wanting to lean in.”

The first step would be training the teachers so that they can experience quality online learning. She is starting up the Flexible Learning Group with colleagues and wants “To see professional learning pivot to year-long and cohort-based, where we can bring in worldwide experts by video, and we have them blogging and reflecting and curating and connecting as pods throughout the year.”

Aim for designing flexibility

One of my takeaways from speaking with Irvine is that our education systems didn’t have to be developed to anticipate the disruption that came with the pandemic in order to have weathered it.

Instead, if we had designed flexible systems to embrace all students, to include everyone such as students who need to work, those with anxiety, those who are neurodivergent, those who can’t make it to every single class for whatever reason, no pivoting would have been necessary.

To this end, I had a conversation with Hannah McGregor who is an assistant professor in publishing at Simon Fraser University. McGregor created the peer-reviewed podcast Secret Feminist Agenda and co-edited Whoops, I am a lady on the Internet. She had a lot to tell me about how she saw the pandemic highlighting “pre-existing lines of inequity.”

She reminded me that “school is not a job.”

She explained that, “Remote work is good in some ways, but in a way, it is what the tech industry was looking for. It just seems like it is a late-capitalist dystopia. It has made the system more efficient and has lowered costs.”

Employers could afford to provide $1,000 laptops and still save money. Some students already had the tech, the high-speed internet connection and home office space, along with parents who speak English and who are university-educated. Other students had to share a home computer, were working multiple jobs and were caretakers at home. “Add any kind of disability and students could not handle the kinds of systems that we cobbled together last minute.”

In McGregor’s view, schools were not interested in using their experiences with remote learning to improve education systems and make them more equitable. “I think that universities were using this as an experiment to move to an efficient digital model. They found that online education is more time-intensive. So, they decided to go back to face-to-face instruction.”

According to McGregor, “Education is deeply inefficient,” and online education even more so. “There are lots of things we could have done to make this a more equitable experience and they all are more teachers and smaller classes. Learning online requires a lot more assistance, more tutoring and one-on-one time.”

Right now, McGregor is using a hybrid model to teach so that students can choose whether or not to attend classes without being penalized.

“Officially I need to make any student who chooses to only access my courses remotely apply for accommodations but I am not going to do that. My students can choose how they want to participate in the class.” She tells me that we need to trust students when they tell us what they need to do well in a course.

She feels bad for students who have to run a “gauntlet” of paperwork just to take a course in a way that makes sense for their circumstances. “For me, successful teaching is meeting students where they are at,” she explains.

Efficiency need not be goal one

We need a better system which meets all students where they are at, not just the majority for whom school works fairly well most of the time.

What I have taken away from these conversations which is most useful is this: If we want our education systems from kindergarten right up to graduate-level university to make it through the next disruption, we must revamp them, not for efficiency but for equity and community.

We should be teaching our students to use the tools that connect them not just to the best resources, but to the best resource of them all — which is each other.

Students must be able to claim these tools as their own so that they can continue to build curated portfolios of their own learning and strengthen their connections rather than having them severed when an institution decides that it is time to end them.

In this way, learning belongs to the students rather than the school.

I am reminded of what Irvine told me, that if schools are to learn a lesson from the pandemic, schools need to make a shift not to prepare for the next catastrophe, but to prepare our students for their lives outside of school. “Because,” Irvine said, “It is the right thing to do.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Education, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: