One morning in high school, 39 years ago, while I was wheeling past the school office and past the wall of starry-eyed grad photos of those who’d left the school before me, the boys’ guidance counsellor Mr. Kirkpatrick happened to be in the hallway. He asked me, “Glenda, would you rather be able to walk or to talk?”

I accepted the question as expressing genuine interest and, until quite recently, I thought it was benign. But then it hit me. That question pitted the two main aspects of my disability, my cerebral palsy, against one another.

Which did I want least? Which is more tolerable? Which is more widely understood?

In that moment of clarity, I realized I had been struggling with this internal battle my entire life. Surprisingly, my inability to walk and my inability to talk are not created equal. They are not equally acknowledged, included or accommodated.

I am puzzled by society’s obsession with the ability to walk. That not being able to move about upright, on my own two feet, makes me less of a person; less worthy, less valuable. And worse, it is something that needs fixing or curing. A lack of physical access is frustrating and inconvenient. And in 2021 there is no excuse for it, other than antiquated and ableist attitudes.

However, I find the inability to clearly communicate verbally far more disabling. For some reason, which continues to baffle me, the majority of our society links the ability to speak with the ability to hear and to understand. People talk down to me, talk to the person who might be with me or totally dismiss me. They don’t allow me adequate time to respond or to use my most effective means to communicate — a text-to-speech app that allows me to convert typed text to audio.

When the Accessible Canada Act received royal assent in 2018, I rejoiced! After much advocating by many parties, communication had been included in the definition of disability, which included physical, mental, intellectual, cognitive, learning, communication and sensory impairments. At the age of 51, both of my impairments — physical and communication — had been acknowledged. Included. Finally.

I was further encouraged by “communication, other than information and communication technologies” being included in the list of accessibility standards to be developed. The barriers that I and more than 440,000 fellow Canadians living with communication disabilities (not primarily caused by hearing loss) face are finally going to be proactively identified, removed and further prevented. After living half of a century on this planet, I was cautiously optimistic.

In April 2021, the Accessible British Columbia Act, or Bill 6, received its first reading. Billed to be aligned with federal accessibility legislation, imagine my extreme disappointment and utter frustration when the bill’s definition of impairment only included physical, sensory, mental, intellectual and cognitive impairments. Communication, as well as learning, had been omitted from the definition.

The plain language summary of the legislation offers this explanation for why some disabilities had not been included: “The legislation includes examples of different kinds of disabilities, not a full list of them. This legislation is aimed at removing barriers for all British Columbians.”

My response to this is a raised eyebrow — only because my initial response is not publishable.

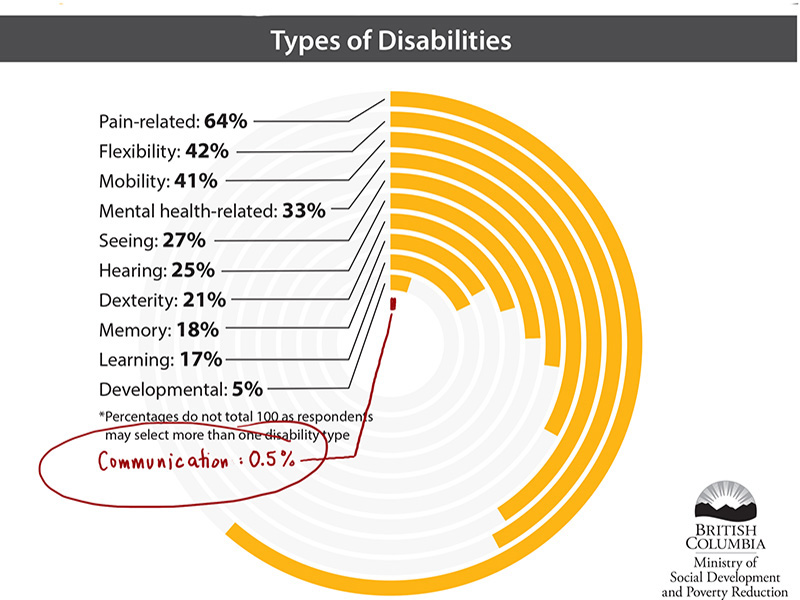

This exclusion is compounded by the omission of communication from the list of disabilities provided in the Accessibility Legislation Infographic.

To me, this continues a systemic exclusion of the approximately 50,000 British Columbians living with communication disabilities. How was it decided which disabilities would be included within the definition? A coin toss? A limited number of characters as if a tweet was being drafted, rather than a piece of long-overdue legislation?

Who made this decision? Bureaucrats more familiar with some disabilities than with others?

Or were the disability organizations that advocated the loudest the ones included? Ironically, advocacy requires communication, which is the disability in this case.

It is unacceptable to omit communication disabilities from the bill’s definition and then offer a patronizing explanation: Oh, those are only examples. Of course, all disabilities are included.

Revisions to Bill 6 should be made prior to the third and final reading. Communication disabilities should not be excluded. Othered.

Thirty-nine years ago, to Mr. Kirkpatrick’s question, I immediately responded “talk” in my wobbly Glenda-ish and scooted off to class, unfazed.

Four decades later, my response would still be “talk.” However, this time I am far from unfazed, no longer that somewhat naive teenager. Today, I feel devalued, dismissed and disregarded.

“Nothing about us without us.” Some aren’t even included in “us.” We remain as “nothing.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: