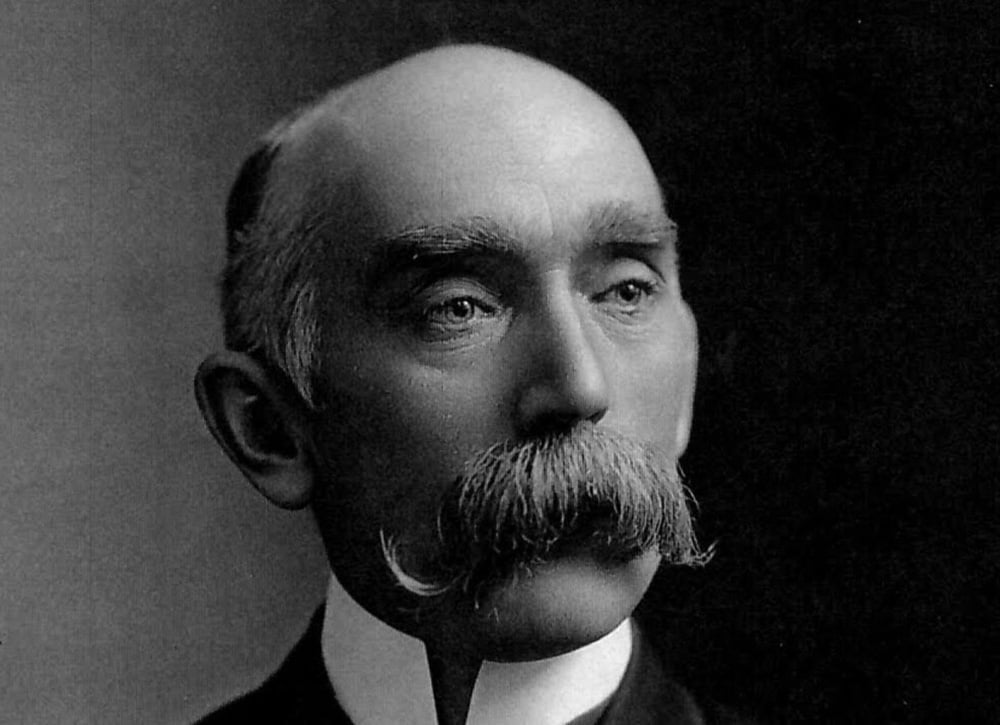

You have probably never heard of Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, but I can tell you this: he would not have been shocked or surprised by the discovery of an unmarked grave on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School last week.

He knew, like Faulkner, that the past is never dead. “It is not even past.”

For 15 years, Canada’s first chief officer of medical health repeatedly warned his superiors that the country’s disease-riddled residential schools had become glorified tuberculosis death camps. He courageously pressed for reforms.

But Bryce’s superiors didn’t listen. They didn’t want to know the truth, and made the physician’s job impossible as only bureaucrats can do.

And so, when Bryce left the government and was no longer oath-bound to secrecy, he wrote a 24-page exposé on the accelerated extinction of Indigenous people willfully being perpetrated in Canada’s residential schools. You can read it here.

Bryce titled his book The Story of a National Crime. The year was 1922.

Canada, a nation full of deep secrets and afflicted by selective memories, can no longer keep this “national crime” hidden anymore.

Nations can deny history, ignore history, minimize history, postpone history and even rewrite history.

But they can’t grow up without facing history for a simple reason. “Knowing the before lets you create a different after.”

The before started a century ago. Educated in Edinburgh, Toronto and Paris, the native of Mount Pleasant, Ontario took up the job of chief officer of medical health in 1904 for Immigration and Indian Affairs.

One of the first statistics that caught Bryce’s eye was this: First Nations reported very low levels of nervous disorders and alcoholism. But tuberculosis was eating their people alive.

The disease had a powerful colonial history. Prior to the eradication of the buffalo and the destruction of an entire ecosystem on the Canadian plains, tuberculosis was rare or non-existent. Although the fur trade had seeded the bacterium, it needed crowding, hunger and homelessness to erupt.

The federal government dutifully provided those conditions after the extermination of buffalo, the chief source of nutrition for many Indigenous peoples.

By withholding food rations, the government forced First Nations into signing treaties and herded 300 different nations into often inhospitable reserves where disease and the politics of starvation became their treaty companions.

As a result, TB began a terrible conquest of Indigenous peoples and helped, along with smallpox and other European microbes, to clear the plains for white settlement.

Cattle, the European replacement for buffalo, also carried a host of diseases including anthrax, brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis.

One infected cow, whether poached or purchased by the government, could infect 100 hungry and immunocompromised Indigenous people with the lung disease.

But the racist theory of the day held that Indigenous people were just weaker than Europeans or naturally inclined to get TB.

Bryce, an expert in the disease, didn’t believe the nonsense and proved it when the government asked him to inspect health conditions in residential schools in 1907.

The federal government set up the schools in 1883 as a colonial force to “assimilate” First Nations and turn them into farmers and fellow extractors of resources.

The schools were, pure and simple, a state-sanctioned tool to remove the culture and identity of subjugated people. The federal government wanted to do to First Nations what the British did to Highland Scots: dispossess them.

Bryce spent three months visiting 35 schools in Manitoba and the Northwest Territories (then including Saskatchewan and Alberta), all located in former buffalo country where people were now starving or undernourished. He found one indignity after another. The buildings were poorly-constructed firetraps with inadequate water supplies. Most had no infirmary. Or proper food supplies.

The schools’ poor ventilation combined with their prison-like atmosphere appalled Bryce. It was “almost as if the prime conditions for the outbreak of epidemics had been deliberately created.”

Bryce noted that the agents of colonialism, the teachers and church officials running the schools, were also reluctant to collect information on the fate of their pupils. He discovered why. In what is today Saskatchewan, of 31 students discharged from the notorious File Hills Indian Residential School in the previous 15 years, only nine had remained alive.

Bryce calculated that the residential schools acted as TB incubators and superspreaders. If children didn’t have TB before they arrived, they immediately contracted the disease in crowded dormitories where children weren’t even allowed to exercise.

And if they were too sick to occupy a desk, they were sent back to their communities, where they spread the disease in crowded reserve housing.

After questioning the principals of some of the schools, Bryce estimated that approximately one-quarter of all Indigenous children attending residential schools for the last 15 years had died from tuberculosis. He wrote that “of a total of 1,537 pupils reported upon, nearly 25 per cent are dead, of one school with an absolutely accurate statement, 69 per cent of ex-pupils are dead, and that everywhere the almost invariable cause of death given is tuberculosis.”

In other words, residential schools typically prepared Indigenous children not for life but death.

Someone eventually leaked what became known as “the Bryce report” to the press where it produced this headline: “Schools Aid White Plague — Startling Death Rolls Revealed Among Indians — Absolute Inattention to the Bare Necessities of Health.”

But most Canadians did not know, care or understand.

Bryce ultimately recommended a dramatic prescription for Canada’s plague schools: supervised medical care (nurses and doctors), better nutrition and better ventilation. (Like COVID-19, tuberculosis is spread by aerosols.)

Bryce also thought the schools should be relocated closer to Indigenous communities. And he recommended that the government take over the schools outright and turn them into sanatoria where First Nations children would live instead of die.

Bryce was no opponent of the colonial order. It was merely that, as historian Adam J. Green notes, “Although assimilation would have certainly been the goal of Bryce’s Aboriginal policy, forced extinction was not.”

Yet neither the government nor churches were impressed by Bryce’s recommendations. They dithered and dallied and calculated the economic costs.

The government then performed the bare minimum “to remove the imputation that the department is careless of the interests of these children.” It set a few standards for diet and ventilation, banned tubercular students and increased the grant for the schools by a small amount. But the children still kept on dying.

Duncan Campbell Scott, the penny-pinching head of Indian Affairs, couldn’t see why the scandalous procession of Indigenous children from boarding schools to unmarked graves was so upsetting.

“When the peculiar conditions are taken into consideration, the department is doing as well as can be expected for the Indians, and to anything further would entail a very heavy expenditure, which, at present, I am not able to recommend.”

Bryce kept on fighting and compiling more statistics. In 1909, the official found more bleak conditions in Alberta. At one school more than 28 per cent of the children had perished, mostly from tuberculosis. Another study in Saskatchewan found 93 per cent of children in the Qu’appelle district were afflicted by TB.

Bryce could see no moral reason why the government could ever tolerate a TB “death rate” among First Nations two to three times higher “than that of an average Canadian community.”

But government didn’t care. By 1914, the Department of Indian Affairs had tired of Bryce’s statistics, and pointedly sidelined the chief medical officer.

Scott, then head of Indian Affairs, informed Bryce that his annual medical reports on TB and residential schools weren’t needed anymore. They cost too much, and the government didn’t really plan on doing anything with the information anyway.

And so the Canadian government, demonstrating a bent instinct for evasion and denial that persists to this very day, never asked Bryce to do any more work related to the Department of Indian Affairs.

Yet Bryce persisted. In a 1918 pamphlet that the government refused to publish, Bryce estimated that the Indigenous population, given the national birth rate, should have grown by 20,000 people between 1904 and 1917. Instead, it shrank by 1,600 — largely due to treatable diseases such as TB.

Irritated by Bryce’s conscience, the government refused to provide its health officer with any more mortality statistics on First Nations. A problem doesn’t exist if a government doesn’t record it.

In 1921, the federal government passed a law that forced Bryce to retire from federal service after 15 years as chief officer of medical health.

But the physician’s heart could not keep silent. The following year he published The Story of a National Crime: An Appeal for Justice for the Indians of Canada. It sold for 35 cents a copy. The book named names and documented the ongoing neglect, complacency and inaction that Bryce witnessed for 15 years.

What bothered Bryce most was the government’s refusal to act, let alone acknowledge the problem: 15 years after his first report, TB still killed children in residential schools at the same alarming rates documented in 1907.

Bryce also decried the implicit racism in the government’s TB response, which disturbingly mirrors in so many ways the current government’s unequal response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Where’s the justice, asked Bryce, in a government that can only allocate $10,000 for the control and treatment of tuberculosis among 105,000 Indigenous people but provides more than $33,000 for the 100,000 white settlers of Ottawa just to handle the hospitalization of their TB victims?

How is it that the city of Hamilton could reduce TB by 75 per cent between 1904 and 1917, yet nothing had been done to keep TB from killing “a splendid race of warriors as the Blackfeet” in Alberta?

The “desire for power,” concluded Bryce, repeatedly over-rode “any higher consideration such as saving the lives of the Indians,” in Ottawa.

But little changed after the book’s publication. Health care for Indigenous people wouldn’t become a government priority for decades.

Until 1945, the minister of mines and resources remained officially responsible for the health of First Nations people, as though TB had become some perverse mineral.

In 1934, the doctor died while on a trip to the Caribbean.

Last year an article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal by Cindy Blackstock, a courageous advocate for Indigenous children, described Bryce as “the whistleblower on residential schools.”

An investigation into the legacy of residential schools and their survivors didn’t begin until a decade ago.

In 2015 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reported more than 3,000 confirmed deaths at the nation’s residential schools.

Government or church officials did not record the names of 32 per cent of the dead.

In half the cases, the government did not even disclose the cause of death.

In a quarter of cases, no gender was reported.

Most of the dead were never sent home for burial. Which brings us back to the unmarked grave in Kamloops.

Now you can’t say that you haven’t heard of Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce.

And now you can understand why he would not have been shocked or surprised by last week’s discovery.

He told the story of a national crime before our collective ears were willing to hear it. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: