Crowded cities can kill!

Even my good friend the esteemed ecologist Bill Rees echoed that sentiment in these pages recently, writing that “contagious disease is readily propagated because of densification and urbanization,” particularly “because of the severe overcrowding of vulnerable people in the burgeoning slums and barrios of the developing world."

What then would be the prescribed alternative? Rearranging how we live so that there is more space between homes, a pattern which replicated gives us sprawl and its longer commutes?

Before we damn the denser, walkable neighbourhood as a diagram for disease, let’s see where this notion arose, and what factors of modern life are the true accelerators of disease and infection. (Hint, it has less to do with how close everyone lives together, and everything to do with an equitable distribution of wealth and investments in public health infrastructure.)

First, the short history lesson.

That dense living is being blamed for epidemics seems to make sense given the explosion of coronavirus cases in New York, Milan, and Madrid. However other cities just as dense have far lower rates of infection spread, thanks to timely measures enacted.

What should we take from past epidemics? We know a devastating plague struck Athens in 430 BC, killing almost 100,000 and leading to its defeat in the Peloponnesian War (although the upside was that it left us with one of the greatest public speeches ever: Pericles' Funeral Oration).

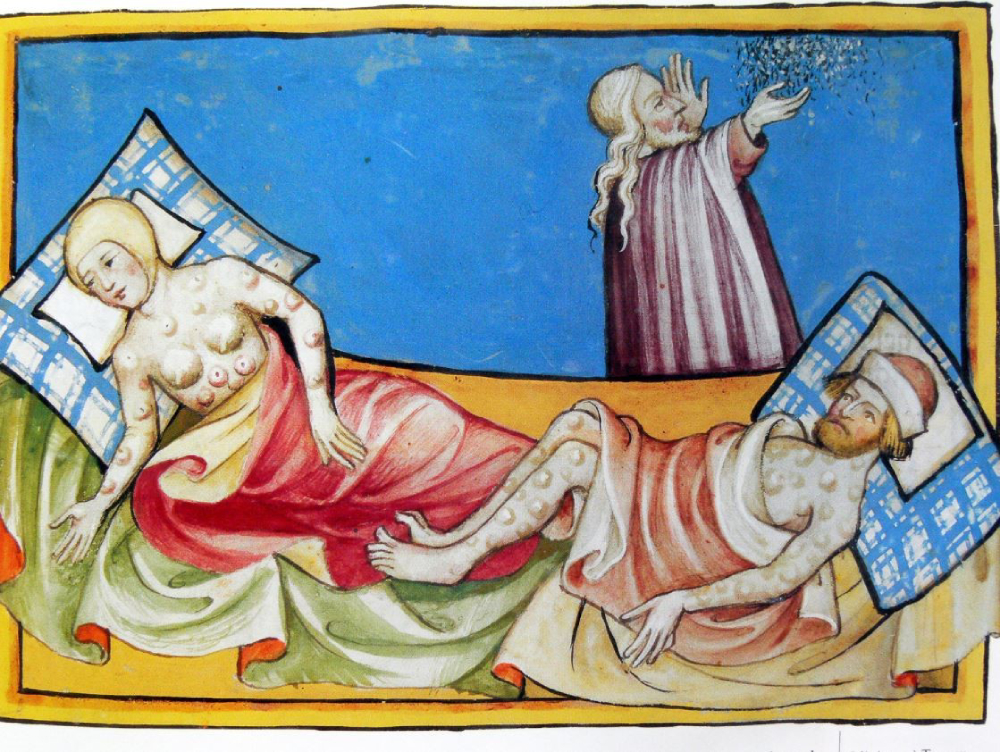

And everyone knows the Black Death decimated previously burgeoning European cities in the late Middle Ages, claiming up to 200 million lives.

Closer to home cholera outbreaks hit New York City between 1832 and the 1870s. But that city’s struggles with cholera are particularly instructive.

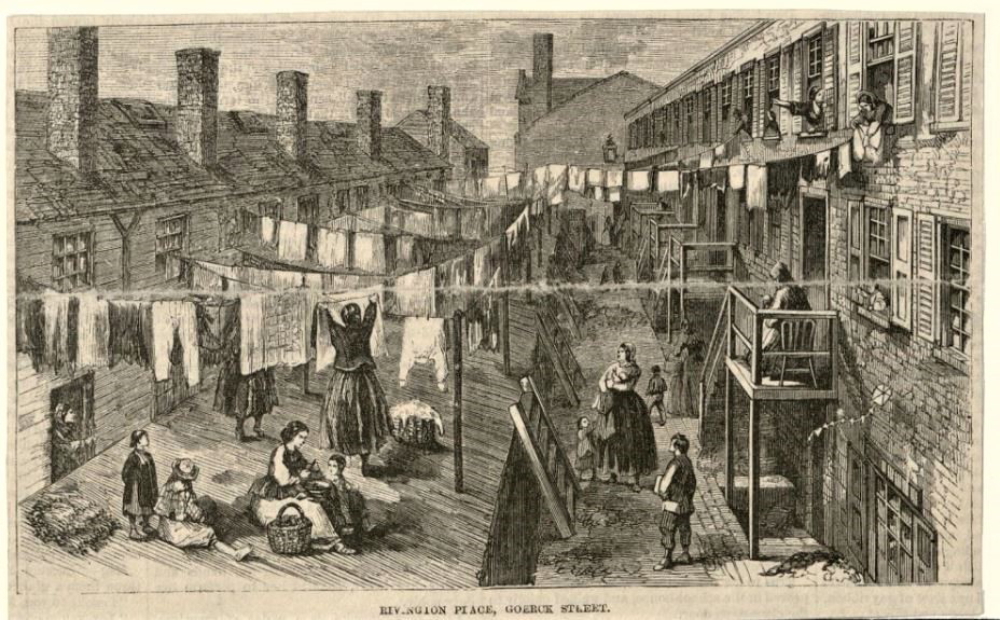

Prior to the mid-19th century, the frequent arrivals of cholera in New York mostly affected, and were blamed on, the city's poor and immigrant communities. Back then local journals would run lurid lithographs depicting what could only be called the local peasant classes roiling in muddy courtyards, hanging clothes across alleys, and drinking intoxicants while children ran unattended and un-bathed through the dirt.

As you might expect this innate prejudice was not likely to galvanize a city-wide commitment to a solution, certainly not a scientific one. It was not until 1854 when a Dr. John Snow of England discovered that cholera was transmitted via water contaminated by the waste of cholera victims that New York's leaders reacted intelligently by upgrading their water and sewer systems.

In the end it was not density or even poverty that was the problem. It was drainage. By 1910 every tenement in the city had running potable water and flush toilets (colloquially called a "crapper" after their inventor Thomas Crapper, whose breakthrough was the "U bend" discharge pipe, which kept smell and disease at bay).

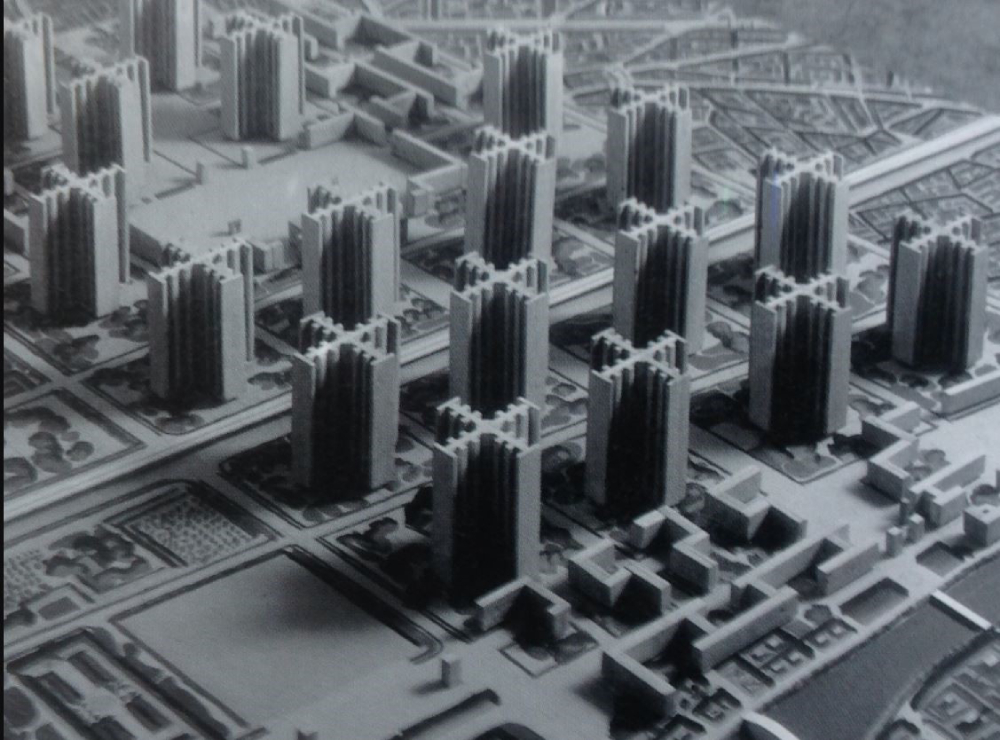

Throughout history, urban form, as opposed to urban infrastructure, has been blamed for disease. Not too long after modern drainage systems defeated cholera, the Swiss/French architect Le Corbusier published what would become an overwhelmingly influential urban design manifesto “Le Ville Radieuse” or “The Radiant City.” Tuberculosis was a rampant disease in the early 20th century, and it too was presumed caused by overcrowded urban conditions. Corbusier's solution was a city of widely spaced high-rise towers where each flat was exposed to ample light and air as a result.

His Plan Voison for Paris, fortunately never executed, would have bulldozed the entire Right Bank of that great city, to open up a vast open field to place scores of identical widely spaced high-rises. His justification? Ridding Paris of disease. His plans never really caught on in France but did catch on in the U.S., with disastrous results when their open areas proved ideal for criminal predation. There’s another city that enthusiastically adopted Corbusier’s approach: Wuhan.

By the 1960s, Corbusier's ideas had gained widespread allegiance among New York City's leading architects and planners. Jane Jacobs famously challenged Corbusier’s health claims and successfully opposed the wholesale clearance of Greenwich Village, then proposed for Corbusier-style "renewal."

By this time the belief that urban density was inherently unhealthy had been undermined by scientific understanding of germs, how they spread, and how to prevent and cure the diseases they cause. Armed with this knowledge, Jacobs revived a nearly lost appreciation for "crowded" urban spaces — like sidewalks, stoops, and parks. People can safely live this way if they are afforded the basics needed for hygiene.

Indeed, epidemiologists have found the anti-urban polemic of Corbusier to be without merit.

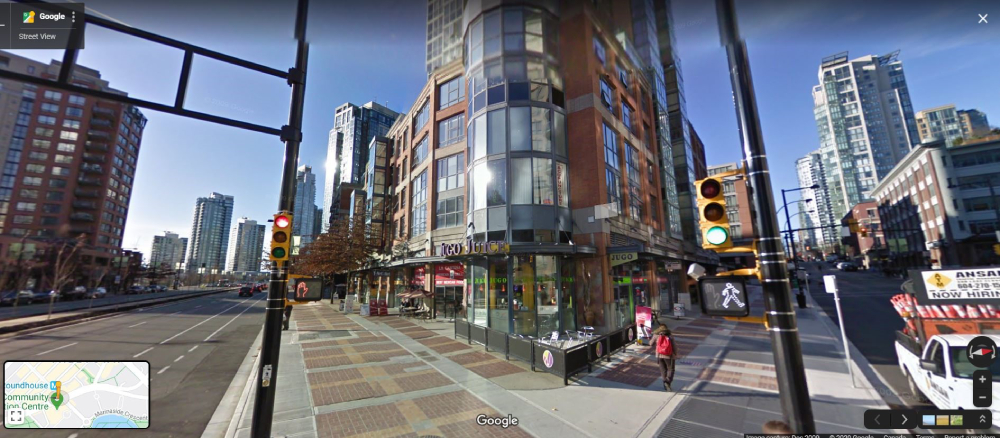

Jacobs’ ideals are manifested in Vancouver’s own Yaletown district, where urban "podium" building bases crowd right up to sidewalks to insure that urban vitality cannot evaporate across indistinct greenswards. Vancouver, like many other cities where public health officials have moved in a timely fashion and held sway, is proving that social distance can be achieved even in dense neighbourhoods. A two-metre distance from each other is as important to maintain in an urban Starbucks as in a suburban Hooters.

In fact, data from New York City suggests that the most heavily affected postal codes are those with medium to low density. Those areas also have a larger share of lower-income minorities, and a greater dependence on transit than in more elite, whiter and denser Manhattan postal codes.

Evidence from both New York and Chicago makes it very clear that social status, low paying service occupations, and dependence on transit seem to be the major vectors for this disease.

In short, inequality is the problem here, not density.

One hopes that when the dust clears we will take these factors seriously and rethink our currently inequitable regional housing and transit strategy.

It’s not okay to force service workers and first responders to live farther and farther away from their places of work in order to afford housing. It’s not okay to force them to make long and, in an epidemic, risky commutes in overfilled transit, just as it’s not okay to force them to make long commutes in expensive air polluting cars.

We need a new vision for what constitutes a "livable region." It should be motivated by scientific evidence and a commitment to social equity, rather than "return on investment." It should put people close to where they need to be and it should place health and social equity first.

The result could very well be more complete neighbourhoods that allow people to live healthier lives. How? In many cases by having us live closer together. Which could in turn place work and shopping within walking, biking or short transit distance of affordable homes, which will lower stress and increase disposable income. These are factors that make people healthier mentally and physically. The size of your yard, not so much. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: