Imagine B.C. run by a party without a single representative from Vancouver, a province where divisions of power break down on strictly geographic lines and ballooning suburbs eventually triumph in a slow and steady demographic war for resources, values and interests.

It's far from impossible, according to experts tracking the trends. As B.C.'s suburbs swell and growth in the already congested city levels off, the balance of power in this province could shift dramatically. And when and if the economy cools, alliances -- which have traditionally spanned city, country and suburb -- could strain and even fracture under the pressure of competition for dwindling public dollars.

Such a future was foreshadowed by the release last month of the electoral boundaries commission report. Most stories on the report focused on the lost seats in B.C.'s Interior. What went less noticed were the gains in suburbia: Three new seats for the 'burbs that surround Vancouver, a fourth for the largely suburban Okanagan Valley.

It's one small part of a cross-Canada trend. Over half of Canadians could soon live in suburbs. And as I wrote about two weeks ago, there is a small but growing body of academic literature that suggests Canadian suburbanites don't just hold more conservative values than do their big city cousins, they also tend to vote that way too. Researchers, pundits and politicians are all scrambling to find out what that trend will mean.

Here in B.C., some people I spoke to for this article foresaw a possible future where a growing rift emerges between Vancouver's inner core and its outer 'burbs. It's a rift that could see the city's power wane and the alliance that binds the governing Liberals buckle.

But the future is hardly set. While everyone agrees that the suburbs will grow, not all are sure what that will mean. Far from the homogeneous sprawl many imagine, B.C.'s suburbs are a fluid patchwork of demographics. With a kaleidoscopic mix of incomes, religions, ages and races, it is tough to firmly predict how the more than 20 cities, municipalities and villages of Greater Vancouver will vote down the line.

Big divide

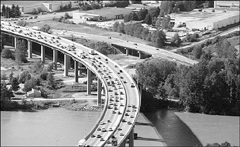

If you drive far enough east from Vancouver, over the clogged Port Mann Bridge and past sprawling Surrey, you end up in the Langley office of John Dyck. In many ways Dyck represents the increasingly powerful suburban voter. He's highly educated, Christian and almost never visits the big city. Dyck, who teaches political science at Trinity Western, a private Christian university, has no problem imaging a potential future where voters in the outer suburbs use their growing clout to wage a battle for resources with their neighbours in the inner core.

It is, in a way, all about access, Dyck told me. The physical distance from his home in Abbotsford to the waterfront in Vancouver isn't that great. But getting there typically involves a lengthy trek through jammed up roads and bridges. So, most of the time, he just stays put.

That creates a problem, he said, and not just for suburbanites. If Vancouver wants provincial money, whether for Olympics or the Canada line or Stanley Park, there needs to be a way for everyone in the greater region to access those attractions. If there isn't, it's hard for those in the 'burbs to justify paying their share. "Stanley Park may be seen as the jewel of the Lower Mainland," Dyck said, "but not if you don't go there."

You haven't yet seen that kind of open jockeying for resources for a simple reason, Dyck added. Both major political parties draw support from both city and suburb and neither can afford to come down to strongly in favour of either one. For the Liberals, though, that might not be true for much longer. The glue keeping the party's disparate mix together is their leader, Gordon Campbell. And whether his coalition survives his eventual retirement remains an open question.

Strains within BC Libs?

Jordan Bateman, a long time organizer for Liberal cabinet minister and suburban heavyweight Rich Coleman, agrees with Dyck's assesement. "As long as [Campbell]'s there, things will be held together," Bateman said. "That's his great strength.... Will there have to be a split [when he's gone]? I think it depends on the next leader."

Bateman, a first term district councilor in Langley, is an unabashed supporter of what he considers the suburban lifestyle. "There's a distinct difference between the way urban and suburban people live," he said. Suburbanites want their own clutch of land. And once they have it, they want to make sure it's in a place where they can raise their kids in safety. It's a type of lifestyle that makes it easy to support a low tax, tough on crime platform, he added.

The challenge for the B.C. Liberals right now is to appeal to the suburban voter without alienating his big city cousin. But that challenge may become a lot less pressing as the suburbs continue to grow and the importance of the city shrinks in comparison.

'Burbs will morph

Of course, all of this relies on a particular idea of suburbia. For any of this to come true, it must also be true that suburbanites really are different and act different and vote different than do city folk. And while there is evidence that that is true, at least as far as voting goes, not everyone is convinced it will remain true as B.C.'s suburbs grow and mature.

"We can't assume these places will stay the same," said Dennis Pilon, who teaches B.C. politics at the University of Victoria. "As people are pushed out of the city by housing prices etcetera, the demographics will change." The beginnings of that change were already evident in the last provincial election, Pilon added. "One thing that's fascinating is to look at the changing voting patterns," he said. "The NDP support in Chilliwack speaks to the changing demography. This is not your parent's Fraser Valley."

Immigrant voters

Another element to consider is the enormous and fast growing immigrant population in Vancouver's 'burbs. While the research shows that suburbanites tend to vote conservative, it's not nearly so clear for suburban immigrants, according to Alan Walks a professor of urban geography at the University of Toronto. In the Progressive Conservative Ontario governments of the 1990s -- considered the prototype for suburban dominance in Canada -- booming 'burbs didn't always mean added support.

"The Mike Harris government removed much of the regulations on developing green field sites and in turn it led to this huge building boom at the edges," Walks said. "So you might think it would have been this great constituency for the Harris government. But no, it's not true. Most of those moving into these new developments are immigrants who are more likely to vote for the (Ontario) Liberal party. So that cancelled out whatever benefits the expansion would have had."

Fraser River 'a wall'

Whether as isolated bergs or thriving outposts in a connected region, how B.C.'s suburbs grow and mature could be the single biggest political story of the next 20 years in this province.

Will that story play out as one of a single maturing region with political competition that weaves in and out of municipal boundaries?

Or as a war between an increasingly isolated core and its booming 'burbs?

The answer has everything to do with the decisions politicians make right now.

Jordan Bateman, the Langley city councilor, isn't optimistic. "The Fraser River is a wall between two completely separate regions," he said. Will there have to be a split between them? "I hope not. But I think we're headed that way."

Related Tyee stories:

- Revenge of the Big 'Burbs

City vs. suburbs is the new fault line of Canadian politics. - Suburbia's Worst Enemy

Reviewed: The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century - My Suburban Summer

An East Van kid sends a postcard from the edge.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: