This week in Vancouver the Bfly Atelier gallery in Gastown is filled up with photography on a grand scale: three dozen enormous unframed prints hung up like bed sheets along the walls and down the centre of the room. The effect is exhilarating, even overwhelming; here photography is triumphant, flagrant, unambiguously public. We stand back to take it in; no leaning into tiny frames set along a museum wall; no hushed communion here. One wishes to speak loudly (at the opening one had no choice; the place was packed) if one speaks at all. We are challenged by this display of photography, taunted, perhaps at moments intimidated. A first impression on entering the gallery: that photography is restored to us.

But what is the nature of this photography so exuberantly displayed? The title of the exhibition is Documents and Dreams; the press release names it the largest show of Canadian documentary in recent memory. The catalogue refers to the photographers as documentarists (an older word might be photojournalists). Each photograph on display is the work of a different photographer, so the show is an anthology, a selection of glimpses. And yet, looking around the room a second or a third time, it is hard to shake off the sense that all these photographs were taken by a single photographer. They share a precise grammar and a common aesthetic: the quick shot, the decisive moment; most of them shot with a 35 mm camera. They are monumental; they are arresting; they beckon to us. And what do they bring us?

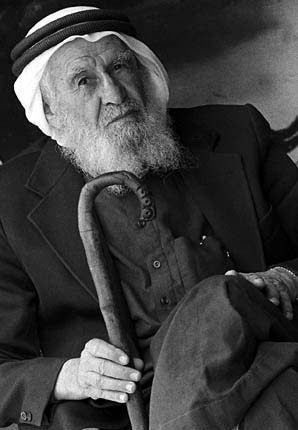

We see children in a refugee camp, a little girl at a road block at Kanehsatake; a bleeding boy in the arms of a white doctor; kids playing with rifles in an Alberta backyard. Tiny notices on the wall identify the photographs (and here we are forced to lean in and squint over each other's shoulders to make out the text): our hypothetical photographer is peripatetic, a relentless traveller to Afghanistan, Pakistan, Israel, India, Bali, Thailand, El Salvador, Italy, Mogadishu, Paris, Ireland, everywhere in the world where trouble is brewing. Even in Canada: the police riot in Quebec City; First Nations reserves; the Vancouver East Side; Poverty in Toronto. We see victims of disease and victims of war and victims of economic injustice; we see pain and poverty, streets and buildings destroyed by war. (There is humour too: a tiger at a wedding, Germans acting like cowboys; a middle-aged woman dressed in the American flag: these images reassure us, perhaps they inoculate us.) Most of these photographs are urgent and we cannot look away (nor do we want to); they are also beautiful, and we are confronted with the familiar problem of beauty and truth in public photography. Indeed, we cannot escape the sense that we have seen all of this before. This is the stuff of "alternative" photojournalism, a narrow range of exotic subjects intended to tweak our consciences. The catalog tells us that the art world has "moved this genre to the margins." Perhaps we are to see this work as suppressed by art galleries, but this would be absurd (the problem of Art vs documentary is as old as photography: it is the very context of photography).

Another possible conclusion: our hypothetical photographer leads a very interesting life!--a ludicrous thought, but not unreasonable; its uneasy corollary is that the photographers are the real subject of this show of documentary.

This display wants to make an argument (mostly implicit) for Art; it wants to say that Documentary is "art"; but the public doesn't care about that question: we look at photographs in order to look at the world.

Photography is an index of the visible: if we don't see it in a photograph, it's not there. What is not there in these images is ourselves: the local public, the audience. We are removed from ourselves by these glimpses, which countenance only the exotic, the distant, and ignore the foreground, the Local. We are made to see the world in the manner of tourists looking at scenery: the foreground is cropped out. Hence we never grasp the source of our confusion, of our desire, of our helplessness. The only image that approaches the Local in this show, that might offer to ground us in a viewpoint that is our own, is a phantasmagoric view of a Calgary street filled with passersby: a beautiful and complex image identified in the accompanying note only as "Street Level," with no mention of Calgary (insider knowledge is required). Rather than identifying the Local, this photograph, like the rest of the show, erases it.

We, the public who are invited to look at these images, are forgotten by this display.

The show is dedicated to Zahra Kazemi, the Canadian-Iranian photographer murdered in Iran last summer. She was arrested while taking pictures in Tehran. Many photographers take risks, but here too there is another lesson: Zahra Kazemi was arrested as an Iranian, not as a Canadian: she was working in the realm of what for her was the Local and not the distant, and for her the risk was real and the outcome terrible.

In his introduction Christopher Grabowski invokes a First Nations elder who stated in a courtroom that he couldn't promise to tell the truth, he could only tell what he knows. Grabowski implies with this example that these photographers are telling us what they know: but the elder in the courtroom is referring to precisely the local knowledge, the home territory, that this selection of photographs fails to identify or to countenance.

If there is to be an alternative photography, capable of countering the sea of images that drowns our perceptions at every turn, these documentarists will be part of it, but as yet there is no alternative photography; nor will there be until what we call Here (not easy to identify and very difficult, if not dangerous, to photograph) and what we call There are equally evident in that photography. Documents and Dreams is a valiant, exuberant show: it must be seen (the web site at www.narrative360.com is attractive but has none of the immediate power of photographs swinging in the breeze); whatever questions this show provokes, it succeeds in putting Photography squarely before us.

Stephen Osborne is editor of Geist magazine ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: