As the Pacific Rim Highway winds through nuučaan̓uuɫɁatḥ nism̓a, or Nuu-chah-nulth territories, a large wooden sign welcomes visitors to homelands of the Tla-o-qui-aht Ha’houlthee Nation on the west coast of Vancouver Island in Tofino, B.C.

The sign is marked with seven posters acknowledging missing and murdered relatives from the nation.

Since 2020, three members of the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation have died in police or prison custody: Chantel Moore, her brother Mike Martin and Julian Jones. In July 2020, James Williams from the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations also died shortly after being released from Duncan RCMP custody.

People from around the world pass this sign, with an estimated 750,000 tourists destined for Tofino visiting Tla-o-qui-aht homelands annually.

Many are unaware of the violence facing the people of the lands they traverse on the way to breathtaking views and surfing holidays.

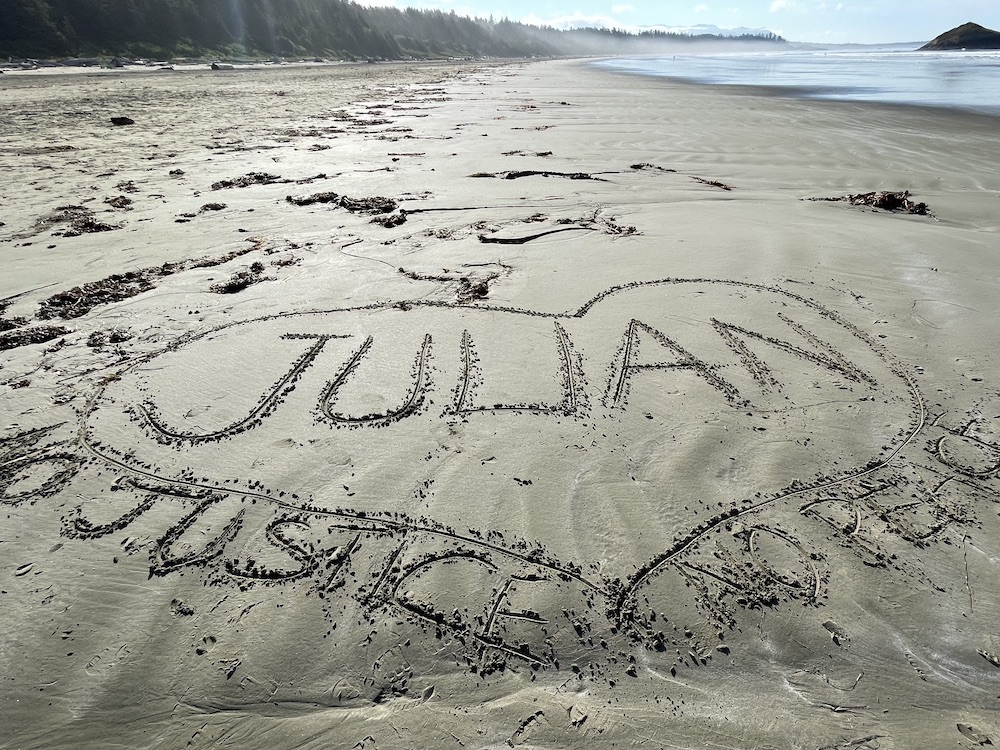

Justice for Julian Jones

When I went to Tofino earlier this month, I was driving Julian Jones’ eldest sister Laura Manson and her daughter Inktsu to Tla-o-qui-aht, their home territory. Over two years ago, Jones lost his life during a violent police invasion of his family’s home. He was only 28-years-old.

Jones was killed by a Tofino RCMP officer on the night of Feb. 27, 2021, in his family home at Opitsaht, a small Tla-o-qui-aht village. He died in his mother’s arms after he was tased and shot by a Tofino RCMP officer.

Upon Jones’ death, B.C.’s Independent Investigations Office, or IIO, asserted jurisdiction over an investigation into whether the actions of the RCMP could amount to criminal conduct.

The IIO is a civilian-led police oversight agency for B.C. The IIO was formed in 2012, after the high-profile deaths of Frank Paul, who is Mi'kmaq from Elsipogtog First Nation, and Robert Dziekanski from Poland.

After 11 years of the IIO investigating police-involved deaths in B.C., no police officer has yet been convicted based on their actions during a civilian’s death — though two RCMP officers were charged after an IIO investigation into the 2017 death of Dale Culver, and the IIO may recommend charges in the 2021 death of Jared Lowndes.

Just a few days after Jones was killed, the IIO announced that it would be appointing an Indigenous Civilian Monitor who would be responsible for reviewing and assessing the integrity of their investigation into Jones’ death.

In 2021, the IIO announced that acting Chief Thomas George had been appointed to the role. He filed his final report with the IIO in August 2022, though the agency only made it public on July 14, 2023.

In November 2022, the IIO publicly announced that it would not be producing a report to Crown Counsel, asserting that the chief civilian director of that agency did not believe that Jones’ death met the threshold for prosecution of potential criminal offenses.

When the IIO concluded its investigation, the agency stated that “a matter related to the incident is currently before the courts” and no public report would be released. The IIO was referring to charges against Jones’ younger brother, which were stayed earlier this year.

Following the stay of criminal charges, the IIO arranged a meeting in Tla-o-qui-aht territory, which took place on July 13, 2023. It took nearly eight months for the IIO to arrange this followup meeting. During that meeting, the IIO and the Indigenous Civilian Monitor provided Jones’ family with their public report and the civilian monitor report, which were embargoed until the next morning.

The July meeting this summer was the family’s first and only opportunity to review the IIO investigation and the decision of the director with IIO representatives. Their loved one has been dead for two and a half years.

Jones’ family travelled from throughout Vancouver Island to support each other. Some made a painful return to their homelands for a meeting with IIO.

Relatives made this journey with no institutional funding or support and instead relied on internal resources and money cobbled together by various fundraising efforts.

A history of colonial violence

Opitsaht is a Tla-o-qui-aht community, considered one of the oldest settlements in B.C., occupying territory colonially known as Meares Island. In a 2021 Narwhal interview, Tutakwisnapšiƛ, also known as master carver Joe Martin, explained that his people have lived in this village site for about 10,000 years.

For centuries, colonial state violence has plagued these territories.

Between 1791 and 1792, Capt. Robert Gray, an American fur trader, ordered the destruction of Optisaht and the kidnapping of the son of Hawith Wickaninnish, a Tla-o-qui-aht chieftain with noted wealth and power.

Some historians suggest that Capt. Gray "feared for his life" and used this to justify the razing of the Tla-o-qui-aht village and abduction of a Tla-o-qui-aht son.

In the centuries that followed, the lands and waters have also been subject to ongoing colonial violence and intrusions by industry — including devastating logging practices that were rampant throughout the Clayoquot Sound.

In 1984, the Tla-o-qui-aht Nation’s steadfast opposition to industry led to the first logging blockade in Canada’s history — in Opitsaht. In addition to internationally recognized work against logging, Tla-o-qui-aht people have also fought mining projects, such as the mining project at Chitaapi in Ahousaht, and fish farms.

Today, Opitsaht is home to about 150 people, and accessible only by boat. In 2022, Tla-o-qui-aht ha’wiih, or Hereditary Chiefs, sounded the alarm on the housing crisis in their nation. Their members are losing their ability to live, work and play on their own territories, while their homeland generates millions of dollars for the tourist economy.

In contrast, four years ago, the Tofino RCMP moved into a new $10 million detachment.

Pervasive distrust

As I made my way to Tofino earlier this month, first stopping at the Tla-o-qui-aht community of Ty-Histanis, the disparities manufactured by settler colonialism were blatant.

In just one year, Canadian police killed two Tla-o-qui-aht Nation members on both coasts of Canada. They were Chantel Moore, killed in June 2020 by Edmundston Police in New Brunswick, and Julian Jones, killed in February 2021 by Tofino RCMP in B.C. In May 2021, a third Tla-o-qui-aht woman was shot repeatedly by the RCMP, though she survived.

After that third shooting, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and Administration and First Nations Leadership Council released a joint statement stating that “the use of lethal force by Canadian police forces against Indigenous peoples is a deadly epidemic in Canada.”

That same year on Sept. 30, 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made his infamous trip to Tofino on the first National Day of Truth and Reconciliation.

After the IIO’s fall 2022 decision not to pursue charges against the RCMP officer who killed Julian Jones, Chief Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council, highlighted the pervasive distrust of oversight agencies like the IIO: “The pattern of unaccountability and injustice for Indigenous victims of police violence, their families and their communities is reprehensible,” Sayers said in a statement.

“It underscores the fact that policing oversight is broken. It begs the question, how can we count on colonial oversight bodies, including the IIO, to hold police accountable when they continue to do the exact opposite?”

I attended two meetings where Jones’ sister Manson and her family sought answers from the IIO. Jones’ family made it clear that they disagreed with the IIO’s report into Jones’ death. Notably, the Tofino RCMP officer who tased and shot Jones did not provide the IIO with a statement, and the IIO could not provide any information on whether or not this officer was on active duty, or where they were currently deployed.

Throughout the meeting with the IIO and in a subsequent debrief, family, friends and supporters repeatedly spoke about distrust and “not being heard” by the IIO.

Family spoke of distorted stories and dehumanizing practices — including the RCMP’s lack of familiarity with Nuu-chah-nulth protocols and grieving practices. When the IIO met with Tla-o-qui-aht Chief and council, the chief civilian director made repeated references to a “knife” that Chantel Moore had. To family members, this needlessly justified the death of a Tla-o-qui-aht woman, while he was seated amongst her relatives.

While Jones’ eldest sister Manson tried to absorb the IIO’s report, its members’ presence in her homelands, and what she and others saw as a lack of cultural humility, she also found words to reprimand both the IIO and the chief civilian director. Manson questioned what she saw as the gatekeeping function of the IIO, whose director is the sole person responsible for deciding whether to send an IIO investigation’s findings to the Crown.

Upon receipt of the IIO file, the Crown decides whether or not to proceed with charges against identified officers, based on their charge assessment guidelines.

When the IIO chooses not to send a file to Crown Counsel, they are effectively deciding that the case does not meet B.C. Prosecution Service’s threshold for assessing charges.

Since Jones’ death, Manson has had to find her voice as an advocate for her family. She, her mother Carol, and her daughter Inktsu have been bringing attention to Jones’ death at rallies and actions on both sides of the Salish Sea.

They frequently join forces with Martha Martin (mother of Chantel Moore), Grace Frank (grandmother of Chantel Moore), Laura Holland (mother of Jared Lowndes), and a community of supporters and allies against police violence.

Consider what solidarity means

This summer, tens of thousands of people will travel to Tofino, to take in the beauty of Tla-o-qui-aht territory. If you’re making this trip yourself, or are planning future travels, I invite you to consider what solidarity means — knowing that this nation has been devastated by police violence in recent years.

If you’d like to directly support the family of Julian Jones, Laura and Inktsu are regulars at the Moss Street Market in Victoria, where they are part of the Indigenous Collective. You can follow their work on Instagram.

When you’re in Tla-o-qui-aht homelands, you can spend your dollars at Tla-o-qui-aht-owned businesses, or businesses that belong to the Tribal Parks Allies Program.

And everywhere you go, you can question the need to continue pouring resources into institutions that directly harm Indigenous people — including the RCMP. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: