The American political sickness has infected us. And it’s hard to see how our democracy can cope.

Start with an Angus Reid poll released last month. It asked people to set out the three most important issues facing the country.

Climate change and environment, said Canadians. For 40 per cent of us, the issue was among the three most important.

The poll found 65 per cent of Liberal supporters considered it among the three most critical issues; 58 per cent of NDP supporters; and 71 per cent of Green voters.

But only eight per cent of Conservative supporters cited climate change and the environment as an important issue.

Traditionally, political parties have competed for votes based on their proposed solutions to what most of us see as problems. Waits for surgery might be too long, for example. One party might argue the answer is higher taxes and more funding for health care; another might campaign on a promise to allow people to pay for private surgeries and skip the queue. Voters can decide.

But when we no longer even agree on problems, our version of democracy doesn’t work. We’re divided into camps, staring at each other with incomprehension, scorn or, occasionally, hatred.

And when the breakdown is centred on an issue that’s widely accepted as a grave threat to humanity, we’re moving away from useful political debate to destructive factionalism.

Then consider an EKOS poll on immigration.

EKOS has been tracking attitudes toward immigration, and toward immigration by “visible minorities,” for 25 years. (Yes, the term has problems, but it’s functional as a survey question. EKOS found answers were unchanged when it asked about accepting “non-white immigrants.”)

In the most recent poll, about 40 per cent of Canadians thought we were accepting too many immigrants; about 39 per cent thought we were accepting too many people from visible minorities.

But 69 per cent of Conservative supporters believed Canada was accepting too many immigrants who aren’t white.

Only 15 per cent of Liberal-leaning voters shared that opinion. About 28 per cent of Green supporters and 27 per cent of NDP supporters thought we should be accepting fewer immigrants who they considered visible minorities.

Among all Canadians, attitudes toward immigration and immigration by visible minorities haven’t changed much over the last decade, EKOS notes.

But among Conservatives, prejudice against non-white immigrants has spiked — from 47 per cent in 2013, to 53 per cent in 2015, to 69 per cent this year.

“What is extremely important is to note that opposition to immigration in general — and visible minority immigration in particular — is not up dramatically,” the pollster notes. “What is dramatic is the level of ideological and partisan polarization on this issue.”

“Racial discrimination is now an equally important factor in views about immigration than the broader issue of immigration.”

Racism is embedded in our society. Many Canadians alive today grew up in a time when overt or institutional racism was accepted. It is still part of our culture, a daily reality. The challenge is to acknowledge that reality, and do better.

But the poll results signal that many Conservative supporters don’t share that belief. More than two-thirds are prepared to proclaim that people with different coloured skin or different religions shouldn’t be allowed into the country.

While our actions have often betrayed our principles, Canadians have broadly accepted the notion that racism is wrong. It is part of the context for our society and politics.

But current Conservative supporters are rejecting that principle. Racism is OK again, at least when it comes to immigration.

EKOS concludes something much bigger is going on. The poll results reveal a surge in support for “ordered or authoritarian populism,” it says.

It’s a global phenomenon, but U.S. President Donald Trump offers a good case study. His supporters — not all — oppose immigration, especially non-white immigration. They don’t trust political parties or other institutions, science, people with expertise or anyone who holds a differing view. They want a strong leader and more police and, as EKOS summarizes, share “a general desire to pull up the drawbridge and return to a ‘greater’ more secure past.”

It is, EKOS notes, “an extremely emotionally powerful force.” And as we’ve seen in the U.S., this kind of populism kills any possibility of rational debate.

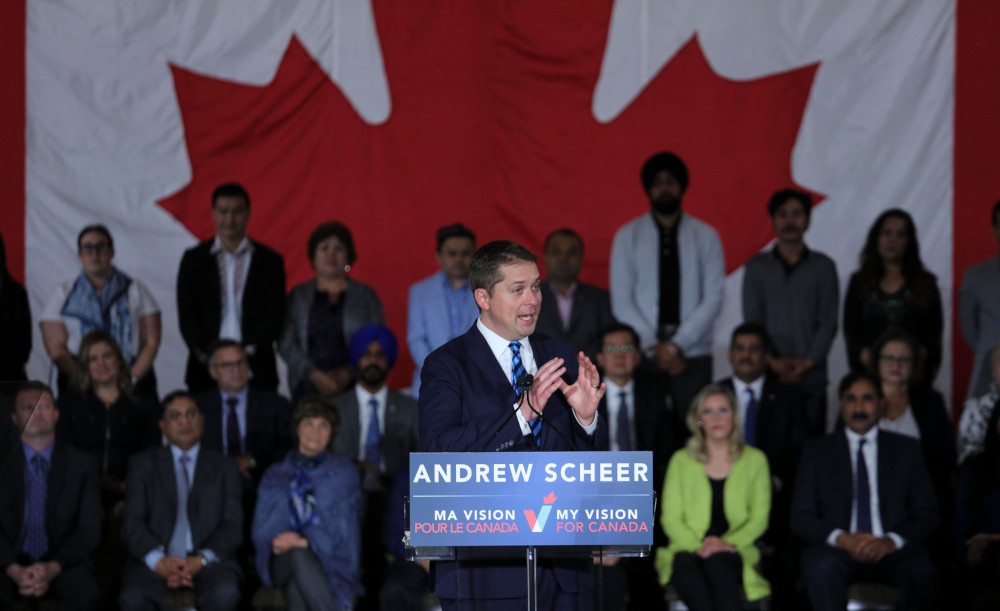

It is no coincidence that so many Conservative supporters are prepared to limit immigration based on race. The party has worked to enflame fears about immigrants, from Stephen Harper’s “barbaric practices hotline” to Andrew Scheer’s “embrace of far-right fear-mongering” over a United Nations agreement on immigration.

Back to the Angus Reid poll, for a last indicator of our political illness.

The pollster asked supporters of the three national opposition parties about their second choice. About 85 per cent of NDP voters had one in mind —Liberal was the leading option. Most Green supporters also had a second choice, with the NDP leading the way.

But more than half the Conservative supporters — 53 per cent — said they had no second choice. (The People’s Party was the leader among those who did have a choice.)

It’s hardly new that many people are committed to a political party, for a variety of reasons.

But the value of political campaigns and debates is eroded when more than half the supporters of one party declare their minds cannot be changed by anything they hear or read, or the qualities of the local candidates.

And the party leader is freed from a sense of responsibility to supporters. No matter how badly he or she behaves, the flock will follow.

It’s nice to end columns in a vaguely positive way. But I can’t find one here.

We’re entering into a post-Trumpian political era in Canada, one where we are divided in ways that don’t allow rational discussion. One where we no longer listen to one another, and where we see enemies, not people with different solutions to shared problems. One where fear — of immigrants, experts, others — replaces hope.

With barely three months before the next election.

The Tyee’s federal election coverage is made possible by readers who pitched in to our election reporting fund. Read more about how The Tyee developed our reader-powered election reporting plan and see all of our stories here. ![]()

Read more: Election 2019, Politics, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: