During an economic downturn, the official unemployment rate becomes an increasingly unreliable indicator of the true health of the labour market. This is because Statistics Canada, when it calculates that rate, requires job-seekers to meet a certain minimum standard of search activity in order to be officially considered a labour market "participant."

If there is no meaningful chance of finding a suitable job in their community, most rational individuals stop submitting applications. And this is understandable. But once they stop actively seeking work to the satisfaction of Statistics Canada, they disappear from the rolls of the unemployed. They are now called discouraged workers -- or, even more dehumanizing, "non-participants." Hence the official unemployment rate comes to understate the true extent of labour market slackness.

A better measure, during tough economic times, is provided by the flip side of this statistical coin. The employment rate is a parallel, and more accurate, indicator of labour market conditions than the unemployment rate. The employment rate directly reports the proportion of working-age Canadians who have been able to find and hold a job. It doesn't matter whether a non-employed Canadian submits several fruitless applications per week; the relevant (and painful) fact is merely that they aren't working.

Analyzing the trend in this alternative index highlights the continuing terrible conditions in Canada's labour market. It also refutes the claims -- made often by politicians at both the federal and provincial levels -- that the labour market has now recovered from the recession of 2008-09. For example, federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty has repeatedly boasted of the fact that total employment in Canada -- measured in absolute numbers -- is now higher than it was before the recession hit in 2008. That must mean the labour market has recovered, right? Wrong.

The obvious dimension missing from this analysis is the fact that Canada's population has grown during the years since the financial crisis hit. In fact, Canada's population grows relatively quickly (compared to other industrial countries), with our working age population growing (thanks to natural births and immigration) by 1.3 per cent per year. Our national working age population has thus expanded by over 1.5 million people since the beginning of the recession.

Did job creation since the recovery keep up with population growth? Not remotely. Canada's national employment rate fell from 63.8 per cent of the working age population in early 2008 to 61.3 per cent in July 2009 -- when the recession hit rock-bottom and the "recovery" (such as it has been) began. Since then, the employment rate has bounced back only modestly: to 61.8 per cent of the working age population by March 2013. According to this measure, then, only one-fifth of the labour-market damage from the recession has been repaired in the almost four years since the official recovery began. To get back to the pre-recession employment rate would require an additional 565,000 Canadians to be working today.

Little wonder, then, that on Main Street Canada it still feels like a recession. From the perspective of the employment rate, things have barely improved since the bottom of the recession in summer 2009.

BC's experience: even worse

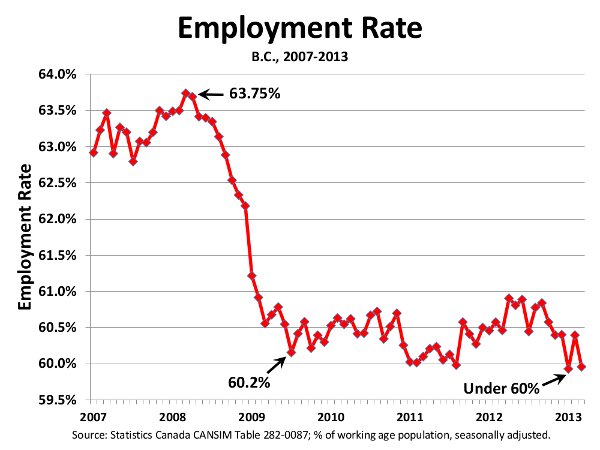

In British Columbia the experience since the beginning of the recovery has been even worse (as illustrated in the accompanying chart). The employment rate entered the recession at almost exactly the same level as for Canada as a whole: 63.75 per cent of the working-age population. The decline during the recession was steeper, however. By summer 2009, it fell to just 60.2 per cent.

Since the recovery officially began in summer 2009, however, things have only gotten worse. The employment rate has only bounced around in subsequent years, with no discernible recovery. In fact, by March 2013 (most recent data available) the provincial employment rate declined below 60 per cent -- slightly lower than in summer 2009, during the worst days of the recession.

By this measure, B.C.'s employment rate performance has been second worst of all Canadian provinces. Only New Brunswick experienced a greater decline in the employment rate since the recovery began. In all other provinces, the employment rate increased.

From a longer-term perspective, B.C.'s labour market star has faded even more clearly. In the 1990s, B.C.'s employment rate tended to be stronger than in the rest of Canada -- an advantage of as many as two percentage points. By 2008, B.C.'s employment rate was only equal to the Canadian average. it is almost two percentage points lower.

The promise that business-friendly tax changes and other pro-employer policies under the Liberal government would usher in a golden age of job-creation for B.C. has been refuted by bitter experience. In the 1990s, B.C. was a relatively good province to look for a job; today it is a relatively bad one. And by this more accurate measure of labour market health, B.C.'s labour market is actually weaker today than during the worst days of the 2008-09 recession. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, BC Politics, BC Election 2013

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: