"We need action not only to end the fighting but to make the peace." -- Lester B. Pearson

Spoken by Lester B. Pearson in 1956, these words grace the side of the peacekeeping monument in Ottawa. They also provide insight into a difficult but worthwhile task that Canada may well be asked to fulfill in the West African country of Mali.

Pearson knew a great deal about war, having served in both the army and air force during the First World War and as a diplomat in London and Washington during the Second World War. When Pearson spoke about making the peace, he was drawing a distinction from two other types of missions: the defence of one's country from outside attack, and forward-leaning interventions aimed at defeating opponents overseas.

Defending the country from outside attack is the fundamental role of the Canadian Forces. Some overseas missions will also be necessary: during the Cold War, the principal duty of Canadian soldiers was not to make the peace, but to guard against the Soviet threat. From sailors in the North Atlantic, to pilots on patrol over West Germany, they protected both Canada and our NATO allies.

Other overseas missions will take place in circumstances where there is no real military threat to Canada. The "counterinsurgency" mission in Afghanistan was optional, from a security perspective, since Al-Qaeda had relocated elsewhere by 2005 and the Taliban posed no significant threat to Canadians in Canada.

Peacekeeping is also optional, insofar as it does not address direct threats to this country. It is something that Canada traditionally did to promote our long-term interests. Between 1956 and 1992, Canada was often the single largest contributor of U.N. peacekeepers.

Today, Canada occupies 55th place with only 11 military personnel and 119 police officers participating in U.N. peacekeeping missions. Logistical and personnel constraints in Kandahar were only partly responsible for the downward trend, which began before 2005.

The retreat from peacekeeping has been a political decision, as was demonstrated in 2010 when the U.N. wanted to place Canadian General Andrew Leslie in command of its 20,500-soldier force in the Congo. It was initially reported that the Canadian Forces were "angling to take command of the U.N.'s largest peacekeeping mission," and the required deployment of just one general and a couple of dozen Canadian troops "would be small enough not to make any impact on resources." But then the politicians stepped in, with the Department of Foreign Affairs explaining: "We're fully engaged in Afghanistan until 2011, and that's what we're concentrating on for now."

Peacekeeping works

For more than a decade, commentators with close links to the Canadian military have argued that peacekeeping is passé, and counter-insurgencies are the new reality. They point to the failed U.N. missions in Bosnia, Somalia, and Rwanda, where peacekeepers were forced to stand by -- due to inadequate mandates, equipment, or numbers of personnel -- while thousands of civilians were killed. They often overlook the core reason for those failures of the early-1990s, namely, a lack of political will, not on the part of the U.N. as an organization, but on the part of its member states.

A learning process was also underway, as the end of the Cold War enabled the U.N. to take on more robust and complex operations. As a result of that process, peacekeeping has evolved significantly since the early-1990s, as evidenced by changes made to the operation in Lebanon.

The U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFL) was formed in 1978. In the summer of 2006, after two months of fighting between Israel and Hezbollah, the Security Council increased the number of troops from around 2000 to 15,000. It also provided a much more robust mandate that authorized UNIFL to take "all necessary action" to protect civilians under imminent threat. Consistent with this mandate, UNIFL was equipped with tanks, artillery and surface-to-air missiles. It has, since 2006, successfully prevented a return to all-out hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah.

There have been many other successful missions. From 1992-1993, the U.N. Transitional Authority in Cambodia stabilized and administered an entire country, ran an election, and managed a transition to a power-sharing government with strong public support, while sidelining the notorious Khmer Rouge. The U.N. Peacekeeping Operation in Mozambique from 1992 to 1994, and the U.N. Transitional Administration in East Timor from 1999 to 2002, had similar mandates and successful outcomes. The U.N. Mission in El Salvador from 1991 to 1995 successfully demobilized the FMLN guerrilla organization, as well as military and police units implicated in serious human rights abuses, and also trained a new national police force. The U.N. Mission in Sudan from 2005 to 2011 led to the end of the civil war, a referendum, and the relatively peaceful secession of South Sudan.

Independent analyses confirm that modern peacekeeping works. From 2003 to 2005, the RAND Corporation compared eight state-rebuilding missions conducted by the United States, and eight by the U.N. in terms of inputs, such as personnel, funding, and time, and the achievement of the goals of peace, economic growth, and democratization. The study showed that seven of the U.N. missions succeeded, whereas only four of the U.S. missions did. It concluded:

"Assuming adequate consensus among Security Council members on the purpose for any intervention, the United Nations provides the most suitable institutional framework for most nation-building missions, one with a comparatively low cost structure, a comparatively high success rate, and the greatest degree of international legitimacy."

The point about costs bears emphasis: U.N. peacekeeping accounts for less than one percent of global military spending. In 2012-2013, the U.N. will spend a total of $7 billion on its 15 missions involving more than 80,000 soldiers. In 2010-2011, Canada alone spent an equivalent amount on its Afghanistan mission, with only 2500 soldiers involved.

In 2008, Virginia Page Fortna of Columbia University conducted a book-length investigation into whether U.N. peacekeeping works. She determined that "peacekeepers make an enormous difference to the prospects for peace, not only while they are present, but even after they depart."

Some critics of peacekeeping argue that most conflicts in the post-Cold War era are civil wars requiring more robust forms of intervention than the U.N. can provide, and that this explains the move to NATO in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan. However, the Human Security Report reveals a decrease of more than 70 per cent in "high-intensity" civil conflicts since the end of the Cold War. It examines the various possible reasons for this decline, and concludes:

"[T]he key factor was the liberation of the U.N. from the paralyzing rivalries of Cold War politics. This change permitted the organization to spearhead an upsurge of international efforts to end wars via mediated settlements and seek to prevent those that had ended from restarting again. As international initiatives soared -- often fivefold or more -- conflict numbers shrank."

The member states of the U.N. are aware of the many successes, for they continue to establish and fund more missions. In the last three years, the U.N. has deployed more peacekeepers than at any time in the organization's history, with more troops in conflict zones than any actor in the world apart from the U.S. Department of Defense. But unlike the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, most Canadians have not heard of these missions -- in part because they are successful, and therefore considered less newsworthy.

Lessons from Afghanistan

Canada joined the U.S.-led counter-insurgency in southern Afghanistan in 2005. Put forward by opponents of peacekeeping as a better fit for the Canadian Forces, the mission was hardly successful. Indeed, the security situation in Afghanistan is significantly worse today than it was in 2005.

As U.S. commander General Stanley McChrystal stated in 2009: "Although considerable effort and sacrifice have resulted in some progress, many indicators suggest the overall situation is deteriorating." According to the United Nations, 2010 was the bloodiest year since 2001 for Afghan civilians, while 2011 was nearly as bad. The number of NATO casualties has also remained high, with 402 soldiers killed in 2012 alone.

As an exit strategy, Canada and the U.S. are expanding and training the Afghan army and police. But the attrition rate of the Afghan army is 24 per cent; in other words, nearly one-quarter of Afghan soldiers leave the army each year. Eighty-six percent of the soldiers are illiterate, making them difficult to train. Adding to the challenge, the Taliban are systematically infiltrating the ranks of the recruits and then turning their guns on the instructors. In 2012, NATO significantly reduced the number of joint operations between Afghan and Western forces because of the frequency of these "green-on-blue" attacks.

It is time to accept that the counter-insurgency mission in southern Afghanistan has failed, and with it, Canada's move away from U.N. peacekeeping.

Canada's niche

Most peacekeeping missions today have more robust mandates, more soldiers, and better equipment than the missions of the early-1990s. What they tend to lack are well-trained soldiers from the developed world. A relatively small number of Canadian soldiers could act as force-multipliers in U.N. missions, by providing leadership and mentoring, and by serving as role models for less-well-trained developing country troops. Contrary to the line of argumentation that took us to southern Afghanistan, if Canada wants to "punch above its weight" militarily, U.N. peacekeeping missions are a good place to start.

Moreover, when Canada acts on behalf of the international community, it bolsters its reputation, thus generating what Joseph Nye of Harvard University calls "soft power" -- the ability to persuade rather than to coerce. Soft power is the principal currency of diplomacy for middle-power states.

Sadly, Canada's soft power has declined considerably in the past decade. In Sept. 2010, for the first time in its history, Canada lost one of its regular bids for a non-permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council. According to international observers, our abandonment of U.N. peacekeeping was a contributing factor in the defeat.

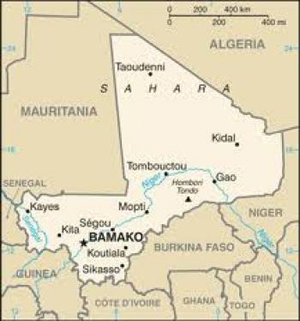

Within the next few weeks, the U.N. Security Council may well authorize an U.N.-led peacekeeping mission to stabilize Mali after the French-led combat mission ends. The success of the peacekeeping mission will turn, in large part, on whether well-trained soldiers from the developed world are involved.

It's a mission tailor-made for Canada; one that Pearson would undoubtedly have embraced. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: