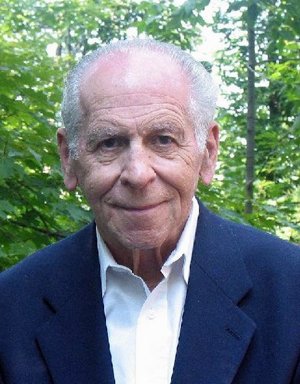

Dr. Thomas Szasz, author of the controversial work The Myth of Mental Illness and one of the most influential psychiatrists of the 20th century, died on Sept. 8. Szasz's seminal work, published in 1961, argued that mental illnesses aren't real illnesses and that people with these labels actually just have "problems with living." He viewed anti-psychotic medications as useless.

The last five decades have transformed psychiatry, which for the most part has moved beyond the psychoanalytic theories that provided the foundation for Szasz's training; contemporary neuroscience research has led psychiatry to view psychotic illnesses as treatable brain disorders.

Nevertheless, Szasz's theories have had and continue to have an enormous impact on mental illness policies. One of the most significant groups that have rigidly subscribed to his ideas has been civil libertarians. Szasz's ideas that all people are responsible for their actions and that no one's freedom should ever be compromised have led these groups in Canada and the U.S. to adamantly oppose any involuntary treatment for people experiencing psychosis.

Only recently, with growing evidence that the lack of insight usually accompanying psychosis is neurobiologically based, have some of these groups begun to reconsider their position.

Liberty's disastrous results

One of the most prominent U.S. think tanks, the right-wing Cato Institute, recently focused its August 2012 journal on rethinking what civil liberties mean when considering severe mental illnesses. While having its usual writers reaffirm the ideas of Szasz, this issue included comments from people like Dr. Ronald Pies, clinical professor of psychiatry at Tufts who attempts to update Cato readers as to why medicine now refers to schizophrenia as a disease.

In the same issue, Rael Jean Isaac, co-author of Madness in the Streets: How Psychiatry and the Law Abandoned the Mentally Ill, offers very useful insights into why Szasz's idea that mental illness does not exist became so popular. Isaac points to the development of the political left's vision in the 1960s of people with mental illnesses as a group who, like other minorities, needed to be liberated. Mental institutions closed and even acute psychiatric beds began to disappear. Ill people without insight into their illness have been left to fend for themselves and now make up a large part of the homeless and the incarcerated population.

Isaac points out the irony that the political left and the right, with their staunch defense of human rights and civil liberties, have both contributed to the disastrous lack of treatment for people with the most severe mental illnesses.

It's also ironic that Thomas Szasz's perspectives are often now enthusiastically endorsed by people in the psychiatric survivor movement. Although these people may feel supported because of Szasz's opposition to involuntary treatment, they may not know about the end points of this line of argument, such as the idea that clinically depressed people should just be allowed to kill themselves. Also, since mental illness doesn't exist in Szasz's views, there should be no insanity defense.

Szasz vividly described his opinions in his article about Vince Li who beheaded and cannibalized a fellow passenger on a Greyhound bus. Szasz argued that Li did not commit this murder because of any mental illness, but because he had a failed life. Unlike the psychiatric treatment team and review board who see Li as doing very well on the anti-psychotic medications he previously rejected, Szasz believed that medications would do nothing for him.

New admirers

Even though some civil libertarians might be rethinking their ideas about what respecting human rights really means when confronting severe mental illness, Szasz's ideas have found a new generation of admirers. Arguments like his are used by those who are now actively opposing all forms of involuntary treatment including community treatment orders in which people receive mandated treatment on an outpatient basis. These human rights advocates choose to ignore the extensive evidence that reports that most people realize they have benefited from receiving the treatment that they didn't understand that they needed.

Currently a repackaged interpretation of severe mental illnesses has become influential. This version, in fact, is reverting back to the psychoanalytic theories that influenced Szasz. Robert Whitaker's bestselling book The Anatomy of an Epidemic, while correctly criticizing the corruption of the pharmaceutical industry, endorses therapeutic methods that dominated psychiatry for most of the 20th century. People who are understood by modern medicine as experiencing psychotic brain disorders are seen as just needing peaceful, nurturing environments in which they can learn to communicate better. Whitaker's view is that people shouldn't be exposed to the anti-psychotic medications that so many find helpful because these medications are too dangerous.

In his thoughtful critique of Whitaker's assertions, psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey points out that inadequate mental health policies have already left almost half of the people suffering from schizophrenia untreated and that life for the vast majority of them has become an experiment in agony.

The rhetoric of the 1960s, which often romanticized mental illnesses, is becoming popular again. Like Szasz's book, the works of R. D. Laing are enjoying robust sales. Laing postulated that insanity is a sane response to an insane society. Psychotic people could be viewed as brave explorers into realms of truth that elude the common people.

This romantic view of psychotic illness is now showcased in HBO's new series Perception. Viewers might be mesmerized by Eric McCormack's riveting performance of a man whom we are told has schizophrenia, and who does much better without medication. As detailed in Marvin Ross's recent article, this character can use his various hallucinations to help the FBI solve their most puzzling cases.

Informed viewers might wonder about the lack of acknowledgement of the real difficulties with the tasks of daily living experienced by many people with schizophrenia, even after their psychotic symptoms have been alleviated through medication. These are the people who qualify for the paltry disability pensions and the inadequate rehabilitation services we make available to them. Perception presents the possibility that they, too -- if they only stop taking their medications -- could reach their potential. Of course, adherents to Szasz's ideas would say that if any of their troubling symptoms re-emerge, they can simply choose to become more responsible people. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: