British Columbia researchers are kicking off a project to re-evaluate the potential health impacts of living near a liquefied natural gas or LNG export facility.

Air pollution from these fossil fuel export facilities comes from flaring, a process where the product natural gas, which is mostly made up of methane gas, is burned.

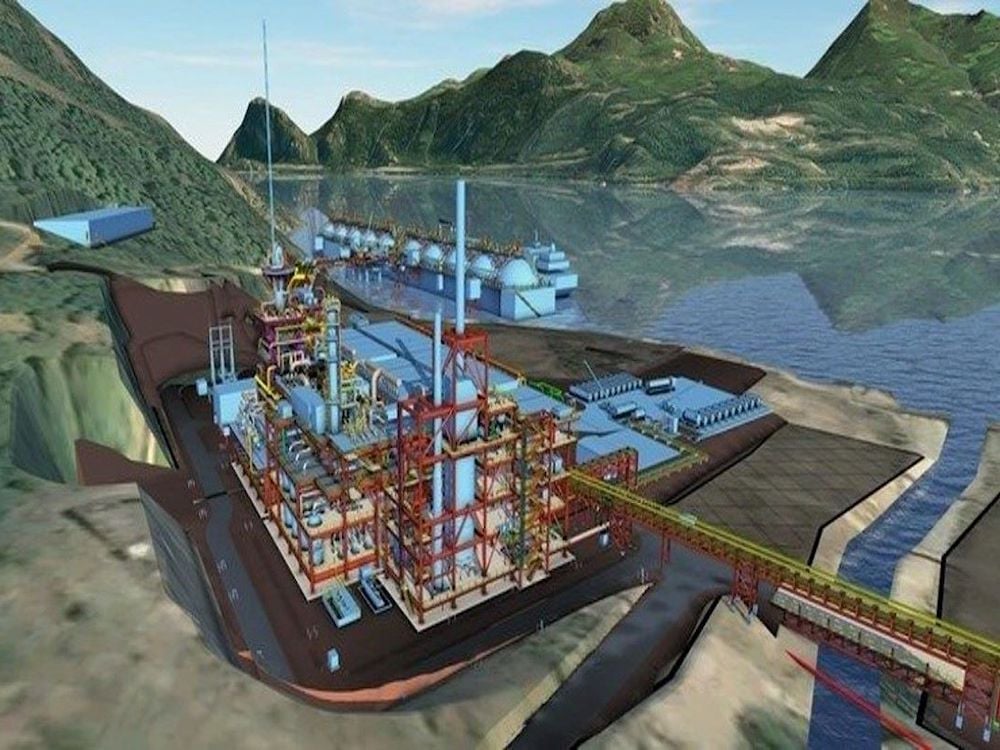

It’s possible B.C.’s LNG export facilities were approved based on health assessments that underestimated how much facilities would flare, says Laura Minet, lead researcher of the study and leader of the Clean Air Lab at the University of Victoria. Minet is also an assistant professor in civil engineering at UVic.

That raises concerns for how the 8,000 people who will be living within 10 kilometres of the Woodfibre LNG facility near Squamish will be affected if operations begin in 2027 as planned.

The study is aimed at trying to find out how much extra air pollution residents will be exposed to and what that means for their health.

The global industry for methane gas has been ramping up in the last decade or so, so most of the LNG export facilities in the United States, Australia, Norway and South Africa came online in the last 10 to 15 years, Minet says.

“Most have had to flare more than anticipated,” she says, and only provide vague reasons like “maintenance” and “construction” for why they have to do so.

B.C. is set to open six LNG export facilities in the next decade or so. The environmental assessments were done on what the company says it would flare — but we now know most projects of this type overshoot their original estimates, Minet says.

Company estimates can be inaccurate because they’re done by contractors hired by the fossil fuel company and not as independent assessors, says Dr. Tim Takaro, an expert on toxicology and public health, professor emeritus in the faculty of health sciences at Simon Fraser University and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment.

Takaro is involved in the flaring emissions study.

“We’re scared those facilities like Kitimat and Woodfibre will flare more than what they said they would do,” Minet adds.

Janetta McKenzie says there are requirements to verify the information in the reports from contractors or third-party verifiers, but she agrees the industry trend of underestimating emissions is “certainly a persistent problem.”

McKenzie is manager of the oil and gas program for the renewable energy think tank Pembina Institute and is not involved in the study.

The industry will report what it is regulated to do, McKenzie adds. “This means it can be improved,” she says. Changing the regulations could lead to more accurate emissions reporting on all types of pollution, including fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide, which is also produced from burning methane gas.

Minet says the project kicks off this month and will run for the next two years. It will be done in two parts and findings will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

First, researchers will use satellite imaging to measure how much other LNG export facilities around the world flare. This will be used to calculate several likely scenarios for how much export facilities in B.C. will flare once they’re online.

The second part will use Health Canada’s Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool to calculate the possible negative health effects from each scenario.

Burning methane gas, commonly referred to as natural gas, produces a number of pollutants that can affect human health, Minet says. Flaring produces fine particulate matter (which is material smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter, or roughly 13 times smaller than the width of a human hair), nitrogen dioxide and volatile organic compounds like benzine and carbon monoxide.

Takaro says a study in Texas found that living near flaring sites is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. Studies in Pennsylvania, California and Alberta found that the closer someone lives to a fracking site, the more likely their baby is to be born with a low birth weight and worse health outcomes.

“Low birth weight causes higher infant mortality and more chronic illness later in life and is associated with poor lung function,” Takaro says. “Babies with lower birth weight is a serious public health problem.”

Exposure to these pollutants is also associated with asthma exacerbation, chronic cardiovascular disease and other illnesses like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he adds.

The most vulnerable people, like the very young and elderly, will be the most affected by this pollution, but “anyone can be impacted by changes in air quality,” Minet warns.

If all six export projects are built, it will add as much carbon pollution as if the province were burning 34 billion pounds of coal every year, according to a report from the Pembina Institute.

So-called natural gas is mostly made up of methane, a fossil fuel that has been found to leak during production and transportation and is 35 times more efficient as a greenhouse gas, trapping heat inside Earth’s atmosphere, than carbon dioxide, Takaro says.

In the middle of a climate crisis, B.C. and Canada are continuing to grow their fossil fuel enterprises, he says. “That means increasing emissions, increasing temperatures, increasing extreme weather events and causing more death and destruction.”

Marketing natural gas as “clean,” notes Takaro, ignores Scope 3 emissions, which happen when a fossil fuel is burned. Canada counts only Scope 1 and 2 emissions, which happen during extraction and transportation of fossil fuels — not what happens when the fuel is burned, which makes up 95 per cent of the total emissions, he says.

“We’re ignoring the biggest impact and pretending it’s not on us. This is mortgaging the future for all people to come after us, including for the young people today. It’s criminal,” he says.

Minet says she is keeping an open mind but if her research finds significant health impacts, she hopes it will “bring the authorities to revisit the choices they made to authorize these export facilities, especially the ones close to human settlements.”

Pembina Institute’s McKenzie says that if the research presents a strong case to reform regulations, it’s unlikely the changes will be applied retroactively. “This is an opportunity to address where some big data gaps are,” she says, and work to improve regulations from there.

The research project is a collaboration between UVic, Vancouver Coastal Health, the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, Simon Fraser University, the University of Toronto, Texas A&M University and the non-profit My Sea to Sky. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: