Last summer, residents in Nelson, B.C., watched in delight as two young bears frolicked on a slide in a children’s park. The impromptu play date was special, as one of the bears was a community favourite that had survived against all odds after her mother and sibling were shot by conservation officers in the fall of 2022.

The black bear was nicknamed Hans Solo by the community — a name later changed to Hansella when she was found to be female — and bear watchers in Nelson were happy the two-year-old orphaned bear had found a friend.

But last month Hansella, who had become an unofficial town mascot, was shot by conservation officers, who tranquillized her and then assessed her as sickly after some concerned residents had reported she was missing fur and had not denned for the winter.

“The bear was not in conflict or presenting a risk to public safety and was in poor health.... Due to its poor body condition, including missing fur, the two-year-old bear was put down as the humane option, with the direction of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship biologists,” said an emailed statement to The Tyee from B.C.’s Conservation Officer Service.

The bear was not examined by the biologists, who made the recommendation for euthanasia based on a phone call from a conservation officer, and no veterinarian was consulted.

The bear’s death shocked Nelson residents and has reignited calls from several wildlife conservation groups and members of the public for a major overhaul of the conservation service, including independent oversight, the use of body cameras, an audit by the B.C. auditor general, a requirement for all orphaned cubs to be taken to a wildlife rehabilitation centre for assessment by an independent veterinarian and changes to conservation officer training.

“The story of Hansella is the story of what is wrong with conservation in B.C. and it’s a story of trauma,” said Katie Graves, co-founder of the Ursa Project, a non-profit society that educates people about bears and the need to secure attractants such as garbage — one of the main reasons for bear-human interactions and deadly outcomes for bears.

The Ursa Project was formed after 17 bears were shot and killed by conservation officers within Nelson city limits in 2022 — even though no known black bear attacks have taken place in the city.

One problem is that although strides have been made in restricting bear attractants in Nelson, many of the city’s downtown and restaurant areas do not have bear-proof garbage containers, and residential garbage is picked up only once every two weeks, Graves said.

Conservationists also point out that even if garbage is kept contained and fruit is picked on time, some bears are still likely to come into communities, either to seek safety or to feed on delicacies such as dandelions. This means paths to peaceful coexistence must be found.

Graves said “2022 was a horrific year for bears. It was one after another and hearing gunfire all the time, and knowing ‘oh no, another one.’”

Among those shot that year were Hansella’s mother and sibling, who were killed two blocks from a school after eating garbage that had been left unsecured by a resident.

A second cub escaped and ran up a tree, where conservation officers failed in their attempts to shoot it. The cub, then about nine months old, stayed up the tree wailing for two days. Northern Lights Wildlife Society in Smithers offered to take the cub in for rehabilitation, but conservation officers refused, saying they would let nature take its course, Graves said.

The cub eventually came down from the tree and disappeared.

Fast-forward to 2023, when an unusual young bear with light-coloured fur appeared in Nelson. Although there was no DNA test, experts agreed it was the same cub, Graves said.

“We were really surprised that our little orphan Hansella had made it through that winter,” Graves said. “She became the town bear and people were rooting for her. She was so, so sweet. She never did anything wrong. She was never aggressive.”

Although Hansella was frequently around people in the Kootenay community, she did not approach them. But as this winter’s cold snap started to take its toll, she was obviously hungry and appeared to be asking for help, Graves said.

Shortly before Hansella was killed, a video of the bear was sent to Abbotsford veterinarian Ken Macquisten, who was asked for his advice on hair loss and body weight.

Macquisten, who specializes in wildlife work and bear rehabilitation, said there was nothing in the video to suggest the bear should be euthanized.

“I don’t know how anyone could come to the conclusion that the bear was better off being dead,” he said.

“The bear had a very short-hair coat but was in decent condition. The reasons for the short-hair coat could have been a parasite causing the hair to be scratched out. But in that case, it should be very itchy and apparently it wasn’t. Or it could be a nutritional issue and potentially reversible,” said Macquisten, adding the video indicated that the bear had a thick undercoat but was missing guard hairs (a coarse outer layer of fur).

“I am not aware of the reasoning for killing that bear. If it was because someone thought it was suffering, I think they are on pretty dubious grounds. I would have felt much more comfortable with that decision had the bear been examined by a licensed veterinarian. I don’t think that bear was even examined by biologists,” he said.

Macquisten believes that in general there is little will among agencies to rehabilitate bears.

“My feeling is that, in most cases, when a bear is dispatched [killed] by a conservation officer, it is for expedience. If conservation officers had the time and the resources, maybe they would save more bears. Saving money seems to be one of their primary concerns,” he said.

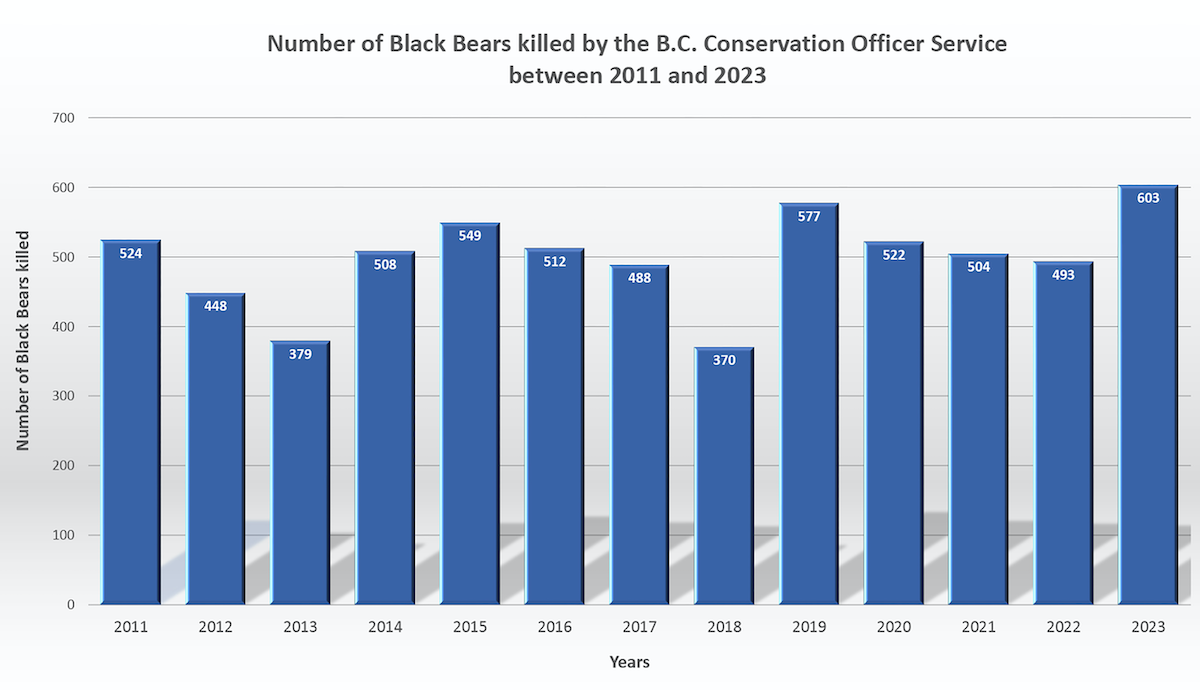

Last year saw a record 603 black bears killed in B.C. by conservation officers, mainly due to fear of conflicts with humans, but also because of accidents or injury. Research by conservation scientist Gosia Bryja has found that over the last two years, when a conservation officer responds to a bear call, 82 to 90 per cent of the time the bear is killed, rather than the officer using non-lethal options such as translocation, hazing (making loud noises or firing rounds over its head to scare the bear off) or sending cubs to rehab.

“This means that eight or nine out of 10 bears are killed once a conservation officer decides to take action,” Bryja said.

Bryja disputes statements from the province that “no conservation officer wants to kill a bear.”

“This is highly speculative. It is impossible to discuss individual conservation officers’ motivations knowing that there is a strong hunting culture within the COS and that each officer comes with complete discretion to apply lethal measures in the field,” she said.

A major concern is lack of transparency and independent oversight of the conservation service, which leaves members of the public with nowhere to go because complaints are investigated by the same department, Bryja said.

“Consequently, residents distrust the system,” she said.

According to a background statement, the provincial Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy and the conservation service support third-party oversight to help build public confidence.

However, changes have been delayed by a recommendation from the Special Committee on Reforming the Police Act calling for a single, civilian-led oversight agency for all police and safety personnel in B.C. — including conservation officers.

The B.C. government has set aside $25 million over the next three years for consultations to develop changes to policing, but it is unclear when they will begin or what they will prioritize.

“In the meantime, the COS has proactively begun sending serious allegations of misconduct to an outside independent law firm for review,” according to the background statement.

But the problem goes deeper than the policies. Bryja is troubled that the system does not consider the trauma inflicted on members of the public when they witness sentient beings being killed, or the emotional complexity of bears, which also suffer distress.

“This was the story of Hansella, who witnessed her mother and siblings being killed. This little girl suffered so much trauma, surviving one winter against all odds. Still, she returned to the community because she trusted she would be safe. She caused no trouble, trying to survive and coexist with people who embraced her. But the system betrayed her,” Bryja said.

Hansella’s death has traumatized many residents, said Marianne Abraham, who has lived in Nelson for 33 years.

“She really touched everyone’s heart. They were emotionally attached to this little bear,” she said, noting that information from sources other than the conservation service did not show Hansella needed to be killed for humane reasons.

“I was heartbroken. I was really devastated. It felt as if it was a moment of sacrifice to bring to light this totally flawed system. There are hundreds of people who are really, really upset by this,” she said.

Distrust of the conservation service is growing, said Abraham, who learned a hard lesson after moving to Nelson and since then has avoided calling conservation officers.

“I had a two-week-old baby and there was a really large bear cruising around my property because I had chickens,” she said.

When the bear started coming around the house, Abraham began to worry and called conservation officers, assuming the bear would be hazed or relocated.

“They came with dogs and treed the bear right in front of me and shot it. I was gobsmacked. I was so traumatized. I said, ‘He wasn’t aggressive, he was eating,’” Abraham said.

“Since that day 33 years ago, obviously nothing has changed, and since then I have always told people not to call conservation because they will come and shoot the bear. That is what they do.”

Ellie Lamb, wildlife adviser to Pacific Wild and a bear viewing guide in the Bella Coola area for 28 years, sees bears as trusting creatures who attempt to get along with humans — to the point that mother bears bring cubs into communities to avoid dangers, such as bigger bears.

“Then suddenly conservation comes in with their semi-automatic militarized weaponry and wipes out the whole family, which is what we saw in Nelson,” Lamb said.

“These are deeply empathetic animals with a sense of culture and tradition. They dish out punishment and they dish out rewards. They have traditional knowledge that they pass on to their cubs,” she said.

Incidents like Hansella’s killing are destroying public confidence, Lamb said. In a recent case on Vancouver Island near Deep Bay, members of the public encouraged a cub off the highway from danger, only to have it shot by conservation officers.

But more people are speaking out. Several municipal councils have invited Lamb to come and educate their communities about managing bear attractants and other ways to reduce the fatalities.

A recent freedom of information request by a member of the public produced a list of bears killed by conservation officers in 2021 and reasons for euthanasia.

The incidents range from a cub stuck in a chicken coop to encounters with dogs, and many involve humans leaving garbage or food where it can be found by bears.

Lamb refers to a description of a skinny cub eating a chocolate bar and refusing to run away when a conservation officer threw a rock.

“It is not just a lack of respect, but an actual sense of war on these animals. Even cruel targeting of helpless baby cubs reaching out for help,” she said.

As a result, Pacific Wild has scrutinized the training that B.C.’s conservation officers undergo, and wildlife specialist Mollie Cameron says it appears to be heavily weighted to firearms training, human-wildlife conflicts and law enforcement.

“So there’s really no education surrounding biology, species’ life cycles, behaviours, ecological threats or education that promote any type of peaceful coexistence. Most of the training and prerequisites they are required to have are heavily centred around law enforcement and hunting,” Cameron said.

However, Environment Minister George Heyman said in an emailed statement to The Tyee that conservation officers have the knowledge, training and compassion to make decisions in the field when it comes to animal welfare and public safety, and are guided by wildlife biologists and provincial wildlife veterinarians.

“It is always unfortunate if an injured bear needs to be safely and humanely euthanized. The health and well-being of wildlife is immensely important to conservation officers and these decisions are not made lightly,” he said.

But public disquiet is getting louder, and conservationists such as Trish Boyum, a wildlife photographer and marketing director for Ocean Adventures bear viewing company, are hoping that the Nelson and Deep Bay bear killings will serve as a tipping point.

“If you cannot count on the B.C. Conservation Officer Service to help us care for a young bear that was orphaned by them, what does that tell us about the ethics, morals, integrity and humanity of the Conservation Officer Service and the laws created by bureaucrats and elected government that allow this to happen?” Boyum asked. ![]()

Read more: BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: