In the Lougheed neighbourhood of Burnaby, there are two towers unlike the glassy skyscrapers sprouting up alongside the tracks of the SkyTrain.

They comprise a single housing co-op, a rarity in this landscape of condos, with 244 units available at below-market rents.

Les Frederick has lived in one of the co-op’s two towers since 2008.

“I couldn’t have asked for anything better,” he said. “The amenities are awesome.”

On a rainy September afternoon, he’s wearing shorts and flip-flops as he strolls through the co-op greeting his neighbours. Frederick runs the pool, which is popular among residents. But for those who don’t swim, there’s also a gym, a billiards room and a workshop with power tools.

“Aside from the brotherhood and the family,” he said of co-op housing life, “the best part about it is that it’s cheaper.”

Last year, he was paying just over $900 a month for his one-bedroom. There were studios for as low as $771 and two-bedrooms for $1,227.

But that affordability was in jeopardy.

The co-op, built in 1981, does not own its land or its buildings. Instead, they were leased from its owner, the pension plan of Local 115 of the International Union of Operating Engineers, from which the co-op got its name of 115 Place.

The pension plan listed the property for sale on the private market. If it was sold, monthly charges could have increased by 40 per cent to as much as double.

Frederick, a retired pasteurizer and ice cream maker at the old Dairyland plant nearby, wasn’t sure where he would go if that happened. In the private market, a basement suite would cost almost double what he’s paying at the co-op. Renting a new one-bedroom condo would be even more.

Ever since he moved into the co-op, he has known he wanted to stay there for life.

“I want to be taken out of here in a box,” he said.

In land we trust

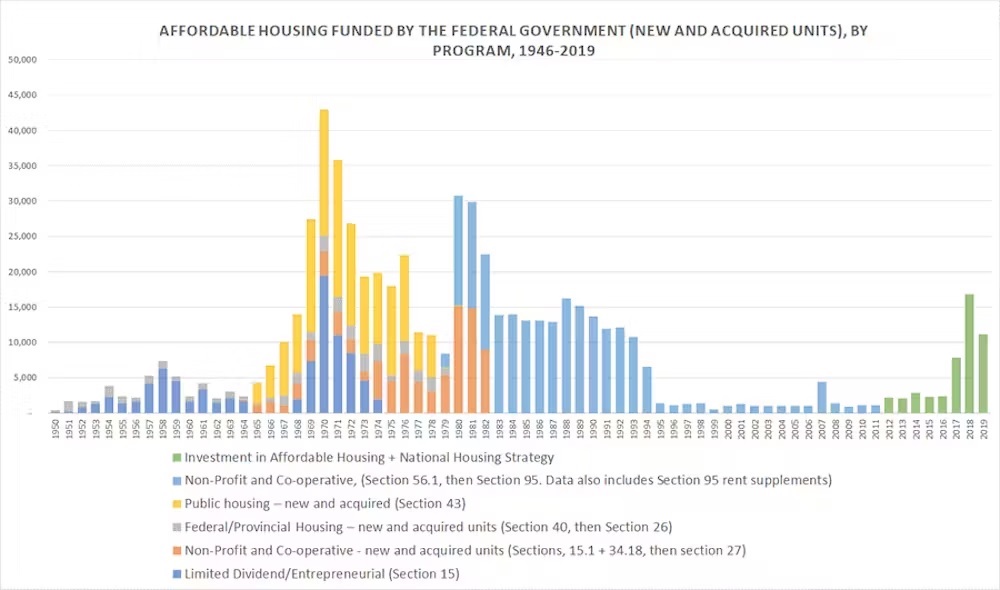

Over 600,000 units of co-op housing were built in Canada between 1973 and 1991. Then the Progressive Conservative government shut down its co-operative housing program in 1992, with the Liberal government subsequently cancelling spending on social housing projects.

With the resulting drought of affordable housing, co-ops like 115 Place offered their residents a rare, affordable refuge as rents and home prices soared.

In 2017, the federal government, with the Liberals once again at the helm, started spending money on affordable housing again, but it’s not to the level of past decades.

That means that as new affordable housing is built, the importance of preserving the older stock of co-ops like 115 Place, public housing, non-profit housing and rental buildings can’t be neglected. For every new unit that rents for the relatively affordable rates of $750 to $2,000 a month, three are being lost, according to the BC Non-Profit Housing Association.

“You’re rolling that rug in front of you with new supply,” said Thom Armstrong, head of the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC. “But if you’re not keeping an eye in the rear-view mirror, it’s rolling up behind you at three times the rate.”

A project of Armstrong’s co-op housing federation has a twofold mission: to rescue old co-ops and to reboot the development of affordable housing, long neglected by the federal government.

That project was the Community Land Trust of B.C.

It’s an unusual model in the province because people “can’t wrap their heads around it,” according to Penny Gurstein, a professor emeritus of planning at the University of British Columbia. However, they become “very interested in it when they understand it.”

A community land trust is a non-profit that provides affordable housing in a variety of ways: acquiring existing properties, developing new ones and potentially offering them to housing providers to run.

For co-ops like 115 Place, a landlord like the land trust would mean no threat of eviction and no one pocketing the profits. All the revenue would go back into making sure that people have homes.

The co-op rescue

Having lived at 115 Place since 2003, Carla Graebner didn’t want to leave either, not even with the impending sale of the land beneath her and the very building she lived in.

Graebner, who works at Simon Fraser University, had been on a coveted wait-list to purchase a unique home. The Verdant development on campus has units available for faculty and staff to buy at a discount compared with market price, on the condition that they would sell it at a discount too.

But both times that Graebner was offered a home, she turned them down.

“I was so pissed off at the pension fund for what they were doing to the co-op and how they were putting so many people in distress,” said Graebner. “I was going to make it as difficult for them personally as I possibly could to be removed.”

She was particularly worried about her senior neighbours on subsidies who wouldn’t be able to afford higher housing costs.

“It took a lot out of our membership, that spectre of losing their homes.”

In 2021, BC Housing attempted to purchase the property from the pension fund. But the fund said they couldn’t come to a “fair” agreement, while BC Housing said the asking price was “inconsistent” with its value.

Still, Graebner was hopeful there would be a deal.

And indeed, a complex one was brokered in 2022. The province, through a BC Housing program, provided about $132.6 million to the land trust to finance the purchase of 115 Place and another Burnaby co-op property owned by the pension fund. The City of Burnaby also contributed about $30 million.

In total, 425 units were saved. The paperwork was finalized with only 20 minutes to spare.

The power of a portfolio

That same year, a Surrey co-op suffered the fate that 115 Place managed to avoid.

Totem’s lease was expiring by the end of 2022. A few years previously, the landlords had offered Totem the opportunity to purchase the property. However, they did not manage to make a competitive offer.

The landlords then sold to a new owner, who demanded that residents pay market-value rent for their units or leave.

In B.C., there are eight co-ops that don’t own their own properties, said Armstrong. When their leases come close to expiring, they too will be looking for a solution to prevent this fate.

There are other reasons why a co-op might consider joining up with the land trust.

A co-op could have deteriorated to a bad physical or financial state.

A co-op’s board might just be tired, with the same members running the building for decades.

“For years, the Achilles heel of the co-op movement is that it never built an engine for growth and preservation,” said Armstrong. “Every co-op is a one-off housing provider. It’s great if you’re looking for a small, intimate, caring, diverse community. If you’re looking for a real estate asset... this is the most disaggregated real estate base you could possibly imagine.”

As a result, co-ops stuck with expiring leases or a crumbling building can’t access the capital needed to save themselves from high costs or displacement. That’s where the land trust can help.

“The land trust is the aggregator,” said Armstrong. “When you combine the assets in a portfolio with the land trust, now the equity grows for the benefit of the group.”

The land trust can access capital from governments, lenders and investors who would otherwise be nervous about dealing with individual co-ops, which are governed by residents volunteering on their boards of directors.

With a portfolio of properties, the land trust has the ability to become a real estate developer, building new co-ops and housing for non-profits on land it owns or leases.

The Community Land Trust was originally founded by the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC in 1993. It stepped up its mission in 2012 after acquiring land leases from the City of Vancouver, at virtually no charge, with the promise of building affordable housing.

Today, there are 20 properties in its portfolio.

When the land trust embarked on its mission, some co-ops accustomed to absolute independence worried that joining the land trust would mean losing the do-it-yourself spirit that they stand for. Armstrong maintains that joining the land trust doesn’t mean giving that up.

“What the land trust model does is say that we’re going to reserve for you what you do best, which is community. You’re going to elect the board of directors, you’re going to accept new members, you’re going to make the rules — how you want to engage the members and the community that you’re creating is entirely up to you.

“We’re going to manage the asset. So we’re going to take care of the roof, the windows, the boiler. We’re going to make sure that in doing that you have a home that will last as long as it was originally intended to last and that your quality of life will not be compromised.

“It’s a perfect partnership. It’s the most significant change in co-op governance and management in 40 years. It’s truly the way of the future.”

‘A very, very deep hole’

The federal government’s abandonment of affordable-housing responsibility in the 1990s wasn’t an exit from housing policy altogether. It was merely a pivot.

Social housing was out. Home ownership was in.

“So that’s what the federal government did: they subsidized home ownership over other types of tenure options,” said planning professor Gurstein.

Over 95 per cent of Canadian homes are in the private market, according to Statistics Canada, the greatest share of all western countries with the exception of the United States.

“The real issue is land availability,” said Gurstein, who is horrified by the thought of governments and public agencies selling public lands. “That’s the big expense. It always has been. So we need to think about how to use our lands in a sound way for the common good, not the ‘highest and best use.’”

Land trusts are gaining popularity in Toronto, where they’ve been used to buy and protect rental properties in neighbourhoods experiencing gentrification. In Vancouver, a deal was just struck with the Hogan’s Alley Society to create one in what was once a historic Black neighbourhood before it was displaced by an attempt to build a federal freeway project.

“It’s a way to ensure affordability in perpetuity,” said Gurstein.

That doesn’t mean the work is easy for land trusts like the Community Land Trust, which is operating in a time of inflation and expensive construction. More costs mean more money needed.

Three sites the Community Land Trust has leased from the City of Vancouver are still waiting for provincial and federal funding to make construction happen. Armstrong says the land trust could have gone ahead to build those projects, but that would have meant renting units at market rates, which defeats the purpose of its mission.

The land trust is also waiting for senior government funding to redevelop the Aaron Webster co-op into a new building with twice as many homes as before. The co-op’s old building was “catastrophically leaky,” said Armstrong, so members decided to transfer its property to the land trust. Thankfully, the land trust was able to relocate the 31 households to another one of its buildings as they wait for the site of their old home to be redeveloped.

There are three categories of policy solutions to make housing as affordable as possible, says Armstrong: reducing capital costs (through grants or waivers like the recently announced one for GST), reducing the cost of debt (through low-interest financing) or reducing rents (through income supplement or rent subsidies).

These days, government programs to incentivize market rental construction are popular. It’s with good reason, because there’s a backlog of demand, “but don’t be misled about the long-term implications,” warned Armstrong.

The market rental apartments built in the 1970s and ’80s under federal programs had affordability agreements that eventually expired. Like any other housing product, “they’ve been flipped multiple times.”

“You’ve got to be smart about the target incentives and subsidies and make sure you get the biggest bang for your buck in the long term,” he said. “When you do the same deal with a community housing developer, you’re getting permanent affordability. Though what’s frustrating today is the financial climate, which has even spooked condo developers into pausing their projects.

“The provincial government is making a record investment on a per capita basis, more than the federal government and all the other provinces combined — and it’s still not enough,” said Armstrong.

“My job is always to say ‘thank you,’ at first, because it’s a historic investment. And then in the next breath say ‘not enough.’ That’s the job, until everybody has a safe, secure, affordable home. This is really symptomatic of how profound the crisis is. We’ve dug ourselves into a very, very deep hole.”

Permanent affordability

Les Frederick and Carla Graebner at the 115 Place co-op were incredibly relieved when the deal went through for the land trust to purchase their property.

“The board did such a good job, negotiating it, working with the different levels of government and trying to keep everyone calm,” said Graebner. “I can’t thank them enough.”

Monthly costs went up by 12 per cent to help pay for renovations.

“Even though that’s very low, that’s a big jump for people because it’s the difference between having internet or a car,” said Graebner.

It shows how catastrophic a doubling of costs would have been for the co-op’s residents if it had been sold to a private buyer.

Even with the increase, residents are still paying less per month than market rents. And now, they know the land beneath them is in safe hands.

“The security makes up for it,” said Frederick. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: