Canada’s labour minister points to decades-old friction between the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the BC Maritime Employers Association as the underlying cause of a month-long labour battle on British Columbia’s docks.

Seamus O’Regan wants to see changes to how B.C. stevedores and their employers bargain, arguing the current system is too prone to protracted, costly labour disputes that shake confidence in Canada’s supply chain and tie up billions of dollars in trade.

“Both sides have to acknowledge there’s a better way of going about this than the way we just did,” O’Regan said in an interview with The Tyee Wednesday.

The roughly 7,400 dockworkers represented by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, or ILWU, voted Aug. 4 to ratify a deal with the BC Maritime Employers Association, which represents 49 companies on B.C.’s ports.

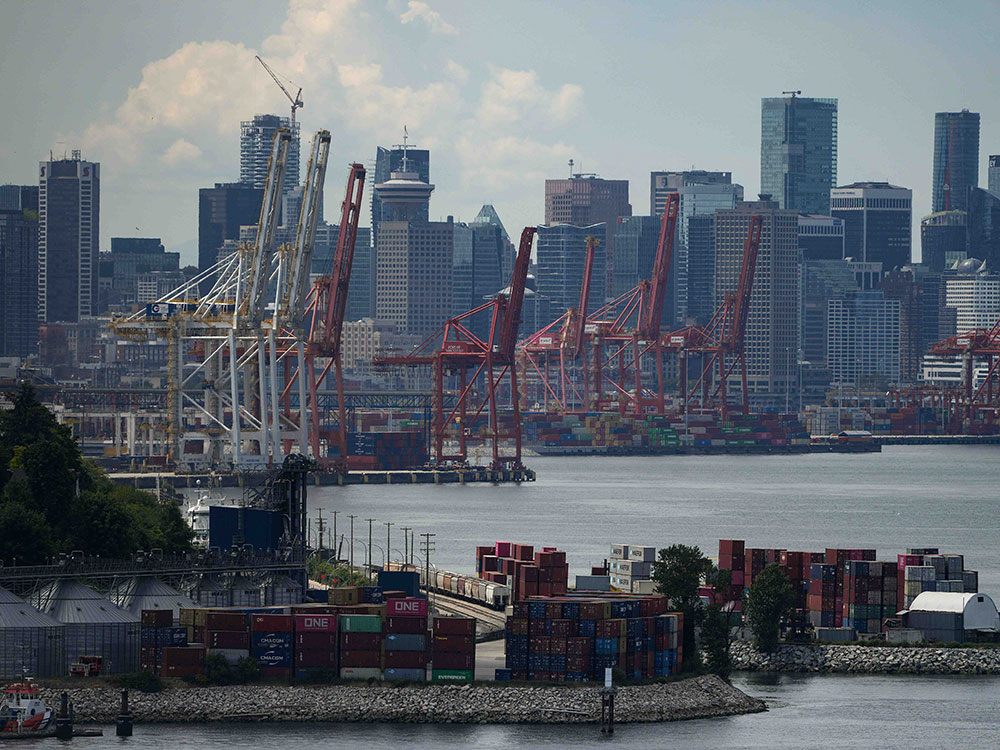

That came after a whiplash-inducing month that began with a 13-day strike that halted work at B.C.’s ports, which are key to Canada’s economy and vital to international trade.

The strike ended with the union and the employers finally agreeing on a contract after two previous deals were rejected by the union’s elected contract caucus and then its members, respectively.

By the end, O’Regan was threatening to force a deal through arbitration.

The episode shook business groups who have called for O’Regan to legislate limits on the union’s ability to strike — something he told The Tyee is not in the cards.

“That goes completely against the collective bargaining process. That’s not what I’m talking about,” O’Regan said.

What he is talking about, he says, are old problems with labour relations on B.C.’s docks that governments have identified, studied and done nothing about.

O’Regan said plans to consult reports commissioned after previous dust-ups, and has also ordered a review of what went wrong with the most recent round of contract negotiations.

The goal, he says, is to ensure that such protracted disputes are less likely to happen in the future.

Any changes, though, will likely hinge on the willingness of employers and the union to make changes to how they bargain.

The Tyee reached out to ILWU Canada president Rob Ashton and the BC Maritime Employers Association for comment. Ashton did not respond.

The association provided a statement from its president, Mike Leonard, who said he “welcomes the government’s review and opportunity to modernize the port labour relations structure to protect the public interest and secure the long-term labour stability of Canada’s ports and supply chain.”

Peter Hall, a professor of urban studies at Simon Fraser University who has extensively studied the port, says he’s not sure amending the bargaining process alone will stop fights at B.C.’s ports.

He notes the disputes are happening amid a backdrop of a changing port and fears from stevedores that automation and outsourcing will chip away at their jobs.

“I don’t disagree with looking at the issue,” Hall said. “I just don’t see what the solution would be.”

No love lost

When the strike began, O’Regan flew to Vancouver to be close to the discussions. He spent two weeks staring daily out of the window of his hotel room at a motionless port.

He hadn’t planned to stay that long.

“Every night, I was extending it one more day, [saying] please don’t kick me out of the room,” O’Regan joked.

There was plenty to talk about. Workers wanted big wage increases to keep up with high inflation — and pointed to record profits reported by shipping companies. They were also worried about losing jobs to inflation and outsourcing.

But O’Regan says there was one issue they couldn’t hash out on a piece of paper: the ILWU and the BCMEA don’t like each other.

“It was clear the relationship between the two was not good,” O’Regan said. “In most instances where I need to get involved, they’re not good.”

Employers and unions disagree at the best of times. But a brief look at history suggests their relationship on B.C.’s docks is especially bad.

In 1923, striking stevedores were intimidated by hundreds of men with shotguns. In 1935, strikers fought armed police. In the 1950s, the pages of the Vancouver Sun were plastered with big ads bought by maritime companies to criticize the ILWU.

But the clearest example comes from a 1975 report, when Justice Peter Seaton was assigned as arbitrator after the federal government legislated striking dockworkers back to the job.

“The bitterness of the union leaders is exceeded only by the intransigence of the employers,” Seaton wrote. “The attitudes are related. Each is nourished by the other.”

Some things don’t change.

In 2010, federal mediators Ted Hughes and John Rooney penned another report highlighting what they believed were the root causes of the labour relations problems on B.C.’s docks.

One of the problems, Hughes and Rooney said, was the unsatisfactory relationship between the parties. Another was the union’s frustrations that the BCMEA was not even the right group to bargain with.

The employers’ association is an alliance of shipping companies, container terminal operators, bulk-break terminal operators and companies that move goods like coal and potash.

Some of those companies, such as shipping firms, don’t actually employ ILWU members. Others are either competitors with each other or operate different companies with different financial needs and interests. Some are fairly small; others are branches of massive, international companies.

Hughes and Rooney argued that this led to internal discord at the bargaining table, since different companies had different priorities. A report in 1995 had raised the same issue.

Hughes and Rooney also accused the union and the employers of engaging in “surface bargaining” — essentially that the two parties bided their time, anticipating the federal government would be forced to intervene through arbitration or legislation forcing workers back to the job.

“The result of this stand-off is that little if anything changes,” Hughes and Rooney wrote.

The events of the 2023 strike echo those identified by Hughes and Rooney. Some Canadian business groups began calling on O’Regan to legislate an end to the strike before it had even begun, something the minister says he found “exceedingly” frustrating.

“It shrinks the worth of workers at the table, and I don’t think it creates any more stability for shareholders and investors on the employer side,” O’Regan said.

He said back to work legislation was a “traumatic” step that should be an “utterly last resort.”

But the calls for O’Regan to legislate union members back to work only became louder as the dispute dragged on. The Port of Vancouver alone is the third-largest in North America. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of products move through it and other ports in B.C. each day.

O’Regan said the scale of that disruption means it becomes all too easy for the federal government to become a proxy in a labour dispute, removing the incentive to compromise at the table.

“The system can be gamed. You’re not going to get real collective bargaining, real give and take at the table if both parties know the government is going to step in at any given moment and legislate you back to work,” O’Regan said.

Hughes and Rooney’s report argued the situation was untenable. “Leaving them to drift is no longer a viable option when the importance of the shipping and transportation industries to a vibrant Canadian economy are taken into account,” they wrote.

They implored then-labour minister Lisa Raitt to take action.

“Our most earnest plea to you is that you not let the commission’s report languish unresolved and gathering dust on a shelf,” they wrote.

“That’s exactly what happened,” said Tom Dufresne. Dufresne was the president of the ILWU when the report was written, during a lengthy standoff between the union and employers.

Dufresne said progress was slow at the table. In his submission to Hughes and Rooney, he argued the employers engaged in “surface bargaining” as they waited on government to intervene. Dufresne said some BCMEA representatives seemed to not know much about the issues at stake.

“You used to have the direct employers would be at the table, the people who actually employed longshore workers,” Dufresne said. “But since about 2008, the BCMEA changed the strategy and the people that are at the table are the ones who represent the shipping lines. They’re almost like a third party.”

Dufresne said the BCMEA was “adamantly opposed” to exploring any of the problems identified in the Hughes and Rooney report.

What happens now

There’s plenty of blame to go around for what caused the latest battle on B.C.’s docks, and little agreement on how to prevent the next one.

UBC emeritus business professor Mark Thompson said watching the dispute unfold reminded him of the Three Stooges.

The employers, Thompson said, didn’t do enough to address legitimate union worries about automation and outsourcing of their jobs.

For its part, the union miscalculated when its leadership accepted a deal that its caucus and later its members ended up rejecting.

And the federal government, Thompson said, may have pushed too hard when it said all options were on the table — which, for many, suggested legislating people back to work.

“It’s Larry, Curly and Moe here,” Thompson said.

In the end, workers got a 19.2-per-cent compounded wage increase over four years, plus a significant boost to a retirement payment and a signing bonus — but only after weeks of uncertainty.

“I think this dispute was a kind of a lesson on how not to do things for both sides,” Thompson said.

O’Regan said preventing that kind of dispute is the goal of his review. He says he wants to make negotiations smoother and simpler.

“It’s not just the process in the moment. How do you prevent the problem? That’s the trick,” he said.

But observers warn a solution won’t be easy to find. SFU’s Hall says the underlying issues on B.C.’s docks are deeply complicated.

“I don’t think there’s a fix to the way bargaining is done that will really solve the problems,” Hall said.

The idea of bargaining with a group smaller than the BC Maritime Employers Association is appealing, Hall said. But he added it could create problems, too.

The current arrangement means workers enjoy flexibility on where they work; if one type of terminal sees a slowdown, a stevedore can work at another. Splitting the bargaining unit — whether by types of terminals or the locations of specific ports — carries risks, Hall said.

“We know what total integration looks like, and it’s bad,” Hall said. “We know what total fragmentation looks like, and it’s bad.”

O’Regan will also contend with a chorus of business groups who want to limit the right of workers to strike by declaring the ports an essential service.

Robin Guy, vice-president of government relations with the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, said the port is simply too important to shutter.

“It’s 25 per cent of our trade that goes through the West Coast ports… it really affects every part of the economy,” Guy said.

In his interview with The Tyee, O’Regan said that essential service designation wasn’t one of the options he was considering.

But Hall and other labour experts questioned how the federal government might meaningfully reform negotiating in the port without giving either employers or the union more leverage.

Larry Savage, a professor who studies the politics of organized labour at Brock University, said O’Regan was trying to walk a tightrope between allies in the labour movement and the business community.

“Maybe I’m cynical, here. I just think there won’t be much that comes out of it. I think it’s just political cover to kick the can down the road past the next election. It’s a way of telling the business community ‘we’ve heard you’ without promising anything,” Savage said.

O’Regan, though, insists this time is different.

“This will not gather dust. This will not languish,” O’Regan said. “I’m determined to figure out how we make sure this doesn’t happen again.” ![]()

Read more: Federal Politics, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: