Toxic drug poisonings killed 179 people in British Columbia in October as the public health emergency’s fatal toll continues steadily at near-record levels.

That’s almost 6 people per day, and 14 per cent fewer than the 207 people who died in October last year. It’s just four per cent more than the 172 people who died in September.

New data from the BC Coroners Service released Wednesday indicates at least 1,827 people have died so far in 2022, putting 2022 nearly on par with the most fatal year recorded.

In 2021, 1,836 people had died by this time, and 2,267 people died in total.

Since the toxic drug crisis was declared a public health emergency in April 2016, nearly 11,000 people have died in British Columbia.

The per capita death rate has more than doubled to 41.7 people per 100,000. Toxic drug poisoning is the leading cause of preventable death in British Columbia and second only to cancer in the number of years of life lost it causes.

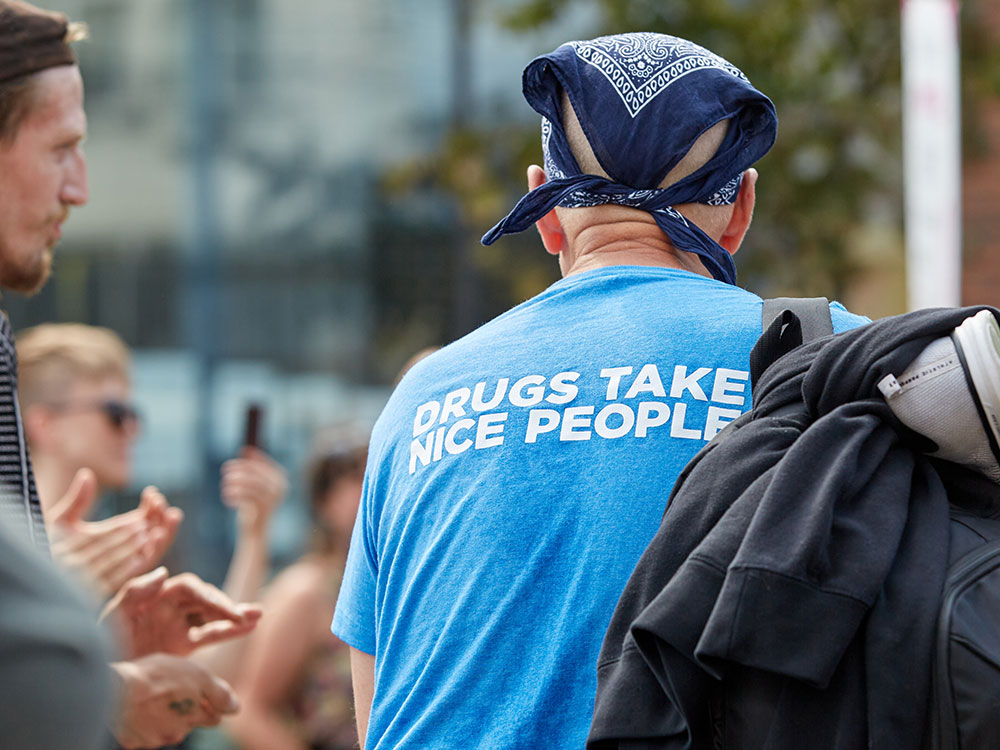

The vast majority of people dying have been men aged 30 to 59. The proportion of people over 50 dying steadily increased to 38 per cent this year. First Nations men and women are up to ten times as likely to die of toxic drug poisonings as their non-Indigenous peers.

The worsening crisis has been driven by the increasing potency and contamination of the illicit supply of drugs in B.C., run by organized crime.

The powerful opioid fentanyl has been identified in more than 80 per cent of people who have died since 2016. Its even more potent sister, carfentanil, killed 190 people in B.C. last year and 100 so far this year.

But experts including the coroner have also linked record fatalities in 2020 and again in 2021 to the increasing presence of benzodiazepines in the drug supply. The sedatives, often used to treat anxiety, do not respond to naloxone and make drug poisonings more complicated and difficult to reverse when mixed with opioids.

Many people are unknowingly taking this “benzo-dope,” which was found in as many as 52 per cent of deaths in January. That rate fell to 22 per cent in August, which contributed to slightly lower numbers of people dying, experts said.

While toxic drugs are killing the greatest numbers of people in Vancouver, Victoria and Surrey, the crisis is affecting every community in B.C.

Vancouver Coastal and Fraser Health regions make up a combined 58 per cent of deaths so far this year. But people die at the greatest per capita rate in the province’s north, where 56 people die for every 100,000 people living there. Smaller communities like Lillooet, Merritt and the Cowichan Valley have the most elevated death rates outside this region.

Wednesday’s report comes two months before personal possession of up to 2.5 grams of some illicit drugs will be decriminalized in an effort to stop the harm and stigma created by the criminalization of drug use.

Despite this Canadian first, a November report on the toxic drug crisis from an all-party legislative committee said the province’s response has lacked urgency to fill gaps in harm reduction services and supports for people who wish to stop or reduce their drug use.

A response letter signed by more than 50 researchers, experts and frontline workers said that the government’s response must focus on replacing and separating people from the toxic illicit supply through safe supply to significantly reduce deaths.

Otherwise, they said, deaths will continue to rise and fall as the drug supply changes, killing both people who use drugs rarely and those who are entrenched substance users.

“No matter how many people go through treatment or are given better support, the drug supply will remain contaminated and until we address it in a real way, the deaths will continue,” said frontline social worker Tyson Singh Kelsall. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: