Rylan Kafara has been on the frontlines of Edmonton’s drug poisoning crisis for a decade.

Now a doctoral ethnography student at the University of Alberta, Kafara said he has been “embedded” in the inner-city community, working as an activist, frontline worker and academic researcher.

With this street-level experience, Kafara did not need to review government statistics to know there was an increase in the number of overdoses and deaths from opioid drugs after the Government of Alberta closed the Boyle Street supervised consumption site in Edmonton’s inner city in the fall of 2020.

“I have seen it on the ground,” he said.

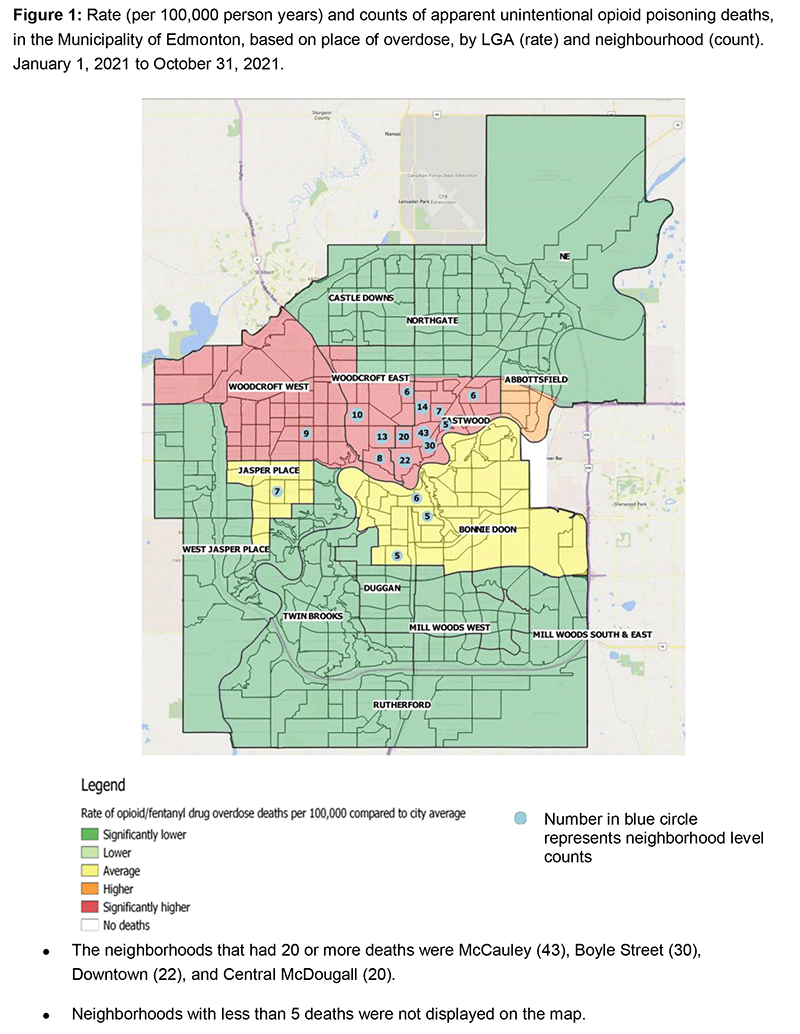

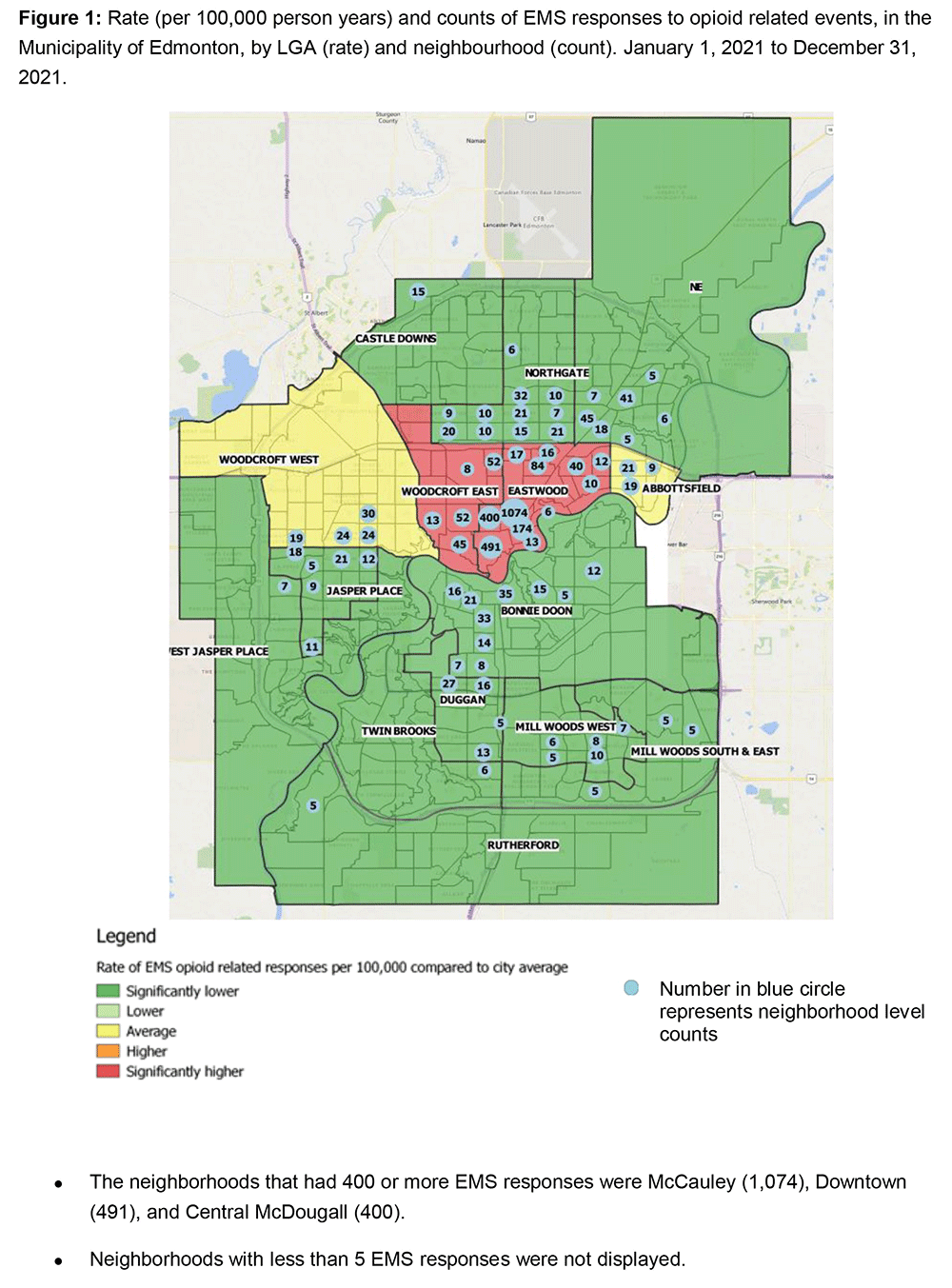

Kafara’s grim assessment is confirmed by internal Alberta Health “heat maps” leaked to The Tyee and displayed at the bottom of this article.

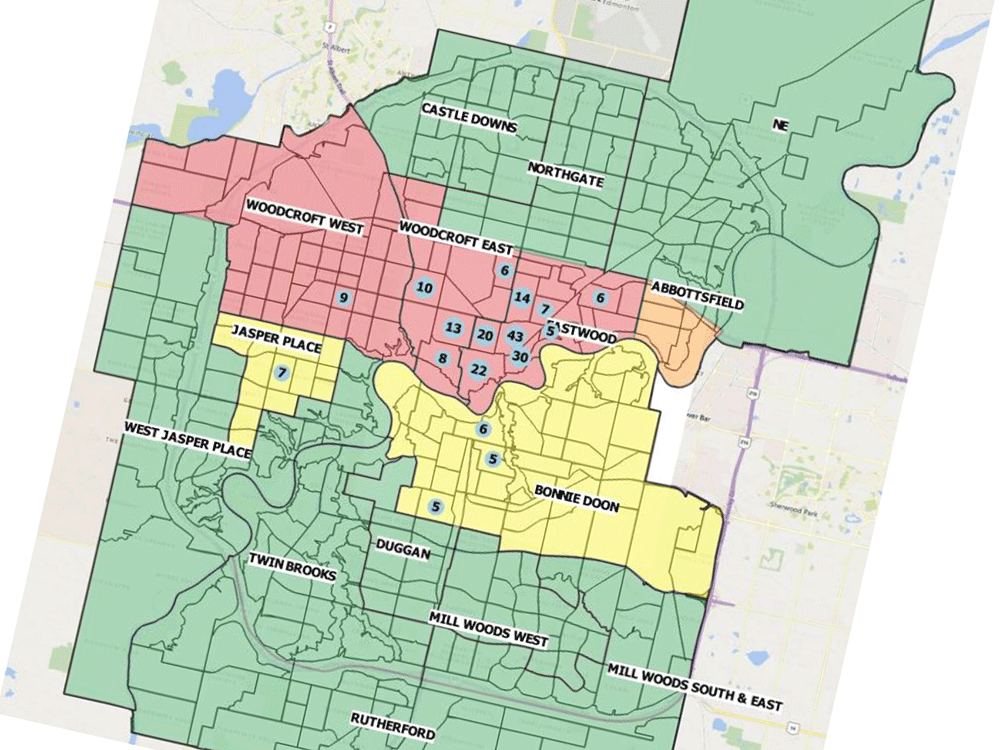

In late 2020, as Boyle Street and other sites in the province were either being closed or not opened as planned, the Alberta government — without explanation — stopped publicly releasing neighbourhood-level maps produced quarterly by Alberta Health.

The maps tracked the number of emergency medical service, or EMS, calls for both non-fatal overdoses and drug-poisoning deaths in Edmonton and Calgary.

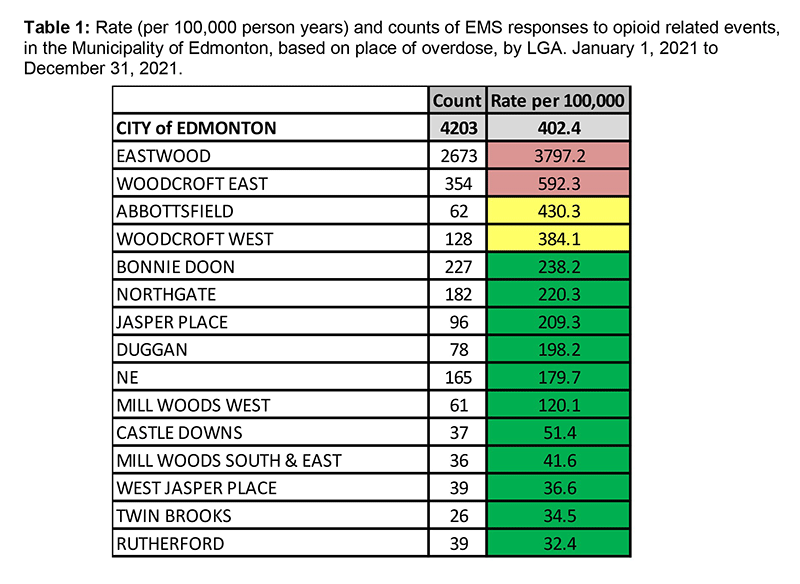

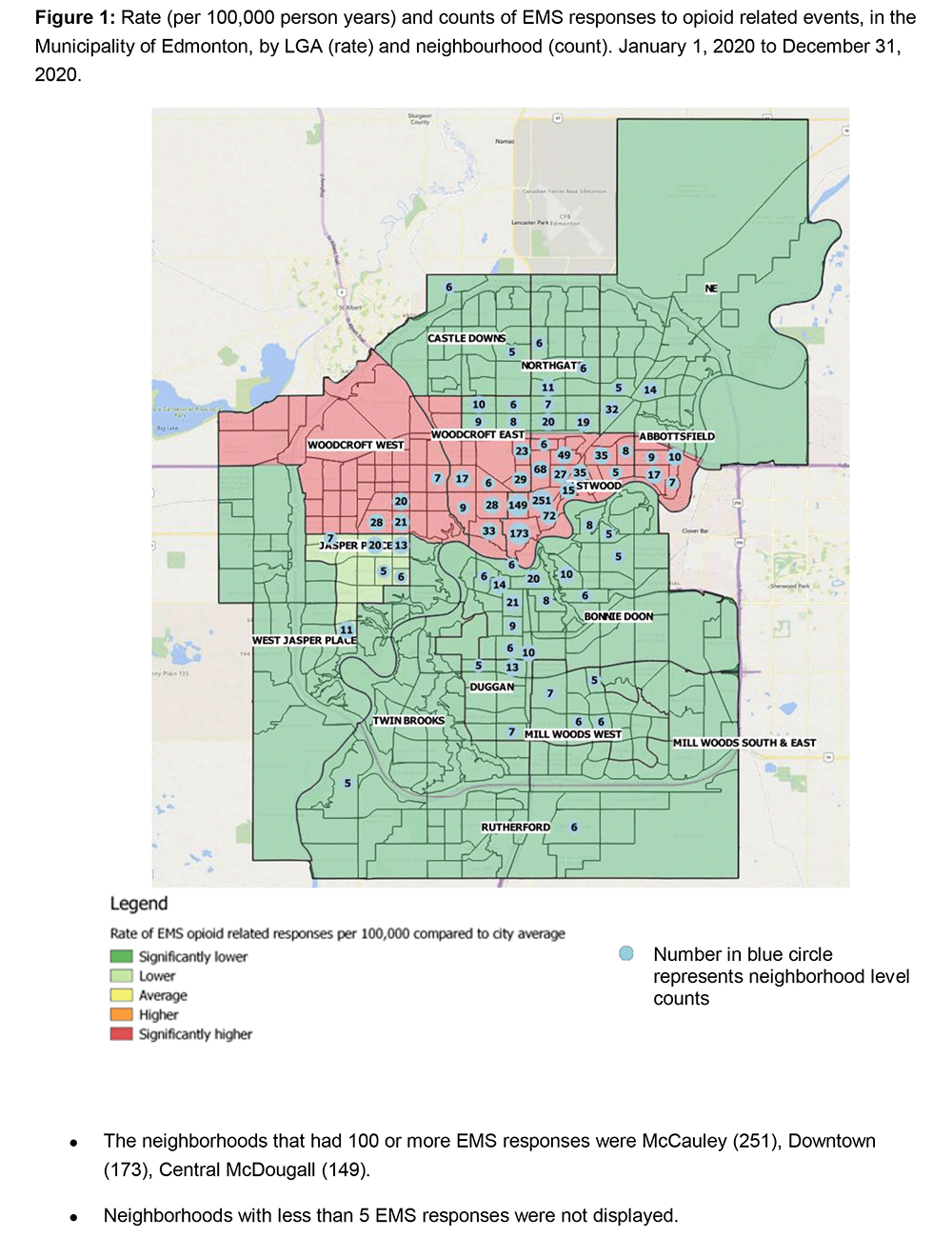

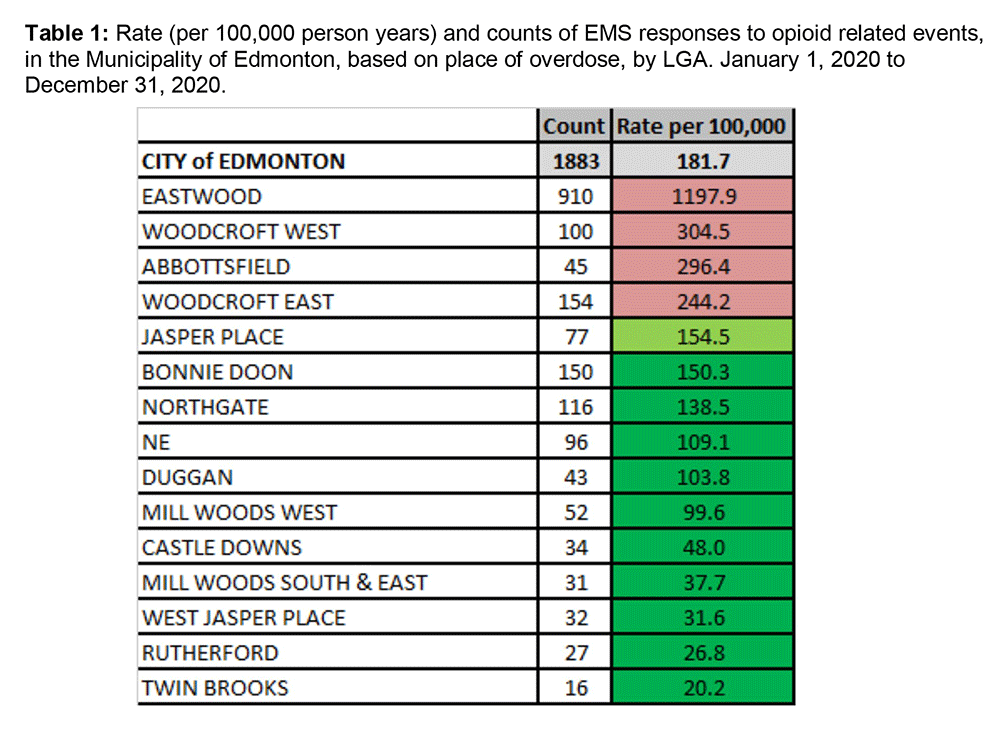

They show the number of EMS responses to overdoses in Edmonton’s main inner-city areas of Eastwood, Woodcroft East and Woodcraft West jumped from 1,164 in 2020 to 3,155 in 2021, a 171 per cent increase.

Kafara suspects the number of overdoses is even higher because the government statistics don’t capture situations in which no ambulance is called after citizens administer naloxone to save someone’s life.

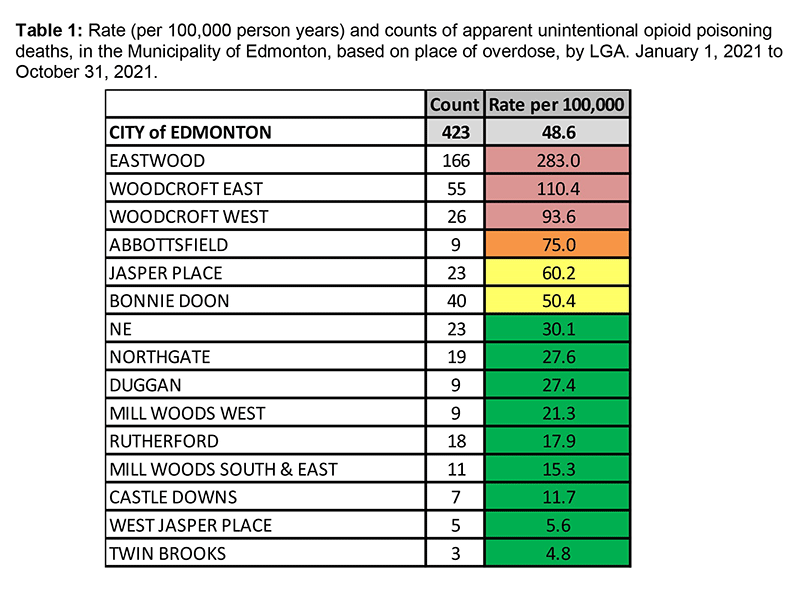

There were 184 drug-poisoning deaths in those three areas from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020. The 2021 map obtained by The Tyee only dates from Jan. 1 to Oct. 31, 2021. Yet the number of deaths rose to 247, a 34 per cent increase in those 10 months.

In 2021, Alberta recorded its deadliest year on record with 1,758 drug poisoning deaths, of which 666 were in Edmonton. In 2020 — another record year for drug-poisoning deaths — 1,351 Albertans died.

Dr. Ginetta Salvalaggio is a family physician and University of Alberta professor who conducts health services research with people who use drugs. She is not surprised the leaked maps show a year-over-year increase in the number of deaths and emergency calls in those Edmonton neighbourhoods.

Nor is she surprised these neighbourhoods bear a “truly concentrated burden of grief and harm right now.”

But Salvalaggio said there is insufficient evidence to categorically state there is a direct causal relationship between the closure of the consumption sites and the increase in EMS calls and drug-poisoning deaths.

“I think we have to speak with community members and service providers and so on to get a better picture of that,” she said in an interview.

“But there is a temporal relationship there. And so is (the closure of consumption sites) the only cause of the increase? Probably not. Was it a contributor? Probably. Do we need more services there, not less? Absolutely.”

The Boyle Street site was closed in the fall of 2020 due to COVID concerns. It never reopened and was officially shut down in April 2021. The government said there were too many supervised consumption sites in one area.

There are still two supervised consumption sites in downtown Edmonton but Kafara has no doubt about the link between the closure of the Boyle Street site and overdoses and deaths.

“Based on this data, they should immediately reopen the closed supervised consumption site, enlarge and enhance it, open more supervised consumption sites, ensure a safe supply of drugs, and end the punitive approach to drug use,” Kafara said.

The Kenney government, however, has made it clear it will not support harm reduction through increased access to supervised consumption sites, and the safe supply of drugs.

The province has instead focused on abstinence-based recovery treatment despite record yearly death rates and ongoing intense criticism from public health experts who have accused the government of putting ideology before science and the lives of drug users.

Experts say the government’s policy ignores the fact that street drugs are incredibly lethal and many victims are not addicted to drugs, but simply recreational users. They also say the government not only refuses to listen to public health experts, it actively attempts to suppress criticism.

In response to the drug poisoning crisis in Edmonton, the Edmonton Zone Medical Staff Association established an Opioid Poisoning Committee to advocate for science-based policies to save lives.

Twice, including most recently in January, the association publicly called on the government to continue releasing the local geographic data on drug-related emergency services calls, overdoses and deaths.

Neither Alberta Health Minister Jason Copping nor Mike Ellis, the associate minister of mental health and addictions, responded to the association’s letters.

In February, the doctors again publicly called on the government to release the information. Again, there was no response from Copping or Ellis.

The doctors said the data should be public so frontline workers and community organizations can reduce preventable deaths.

“This information helps mobilize the resources and efforts in the communities to reduce incidents of harm and death, ensuring that those working on the frontlines of this effort can be where they need to be,” the committee’s February statement said.

The government posts data on its substance use surveillance system online dashboard. But Salvalaggio said the dashboard only provides general information, such as whether an overdose or death occurred in a home or public place and the total number of overdoses and deaths for a specific city.

“They're not telling us at the neighborhood level what is going on,” she said. “And that is really important when you're planning services in a city as large as Edmonton.”

Salvalaggio said the information from the heat maps would also help the government be more transparent in setting policy and could help academics and others to critically evaluate whether those policies are working.

It is now impossible to track whether the government’s abstinence-based recovery policy is working because it doesn’t track how many people enter treatment or how many successfully complete it.

Rebecca Haines-Saah is a public health sociologist at the University of Calgary who specializes in drug use, drug policy and harm reduction. She said when a group of frontline leaders met with Calgary Mayor Jyoti Gondek in January, she asked the mayor to pressure the government to continue providing the heat maps.

“If we are not going to respond to this urgent need by looking at maps, and figuring out how we can get the services to the people who need them, I just don't know what we're doing. It is ridiculous.”

Haines-Saah believes the Kenney government’s refusal to release granular municipal statistics is because it has “clawed back some services, they have closed supervised consumption sites, and they are planning in Calgary to relocate supervised consumption from the (downtown) Sheldon Chumir centre away to other places.

“And so not having that data available kind of keeps all of us in the dark about where the greatest need is, and if their plans are making things worse,” Haines-Saah said.

Ellis, the minister responsible for mental health and addictions, did not acknowledge an interview request from The Tyee for this story or two previous Tyee stories.

The Tyee had difficulty finding experts to comment on the heat maps for this story because some fear the provincial government will cut their grants.

Edmonton Zone Medical Staff Association president Dr. Erika MacIntyre said the number of drug poisoning deaths was so alarming that the association decided a specific committee was needed.

“We threw a whole bunch of our resources, time, personnel, physicians, money into a committee dedicated to this crisis.”

But she said when the government shifted its policy from harm reduction to abstinence-based recovery, at least two physicians who worked in the addictions area and spoke out against the changes “had their funding or their grants threatened.”

MacIntyre said the doctors weren’t even criticizing the government.

“They were just speaking, and really advocating for patients and programs and services.”

“There are always two sides to a story,” MacIntyre said, but when doctors are stopped from publicly advocating, “the public doesn't hear both sides.”

Dr. Salvalaggio, the doctors’ Opioid Poisoning Committee co-chair, was the only doctor who agreed to be interviewed.

Alberta NDP health critic David Shepherd said the Kenney government has a well-documented history of suppressing information.

Shepherd said all the stakeholders — drug users and their families, EMS, police, social service agencies, residents, business owners — with whom he has spoken “have all been very clear that we have seen a spike in drug poisonings.

“This is a government that does not want to be held accountable,” Shepherd said.

“This government has clearly demonstrated they're not interested in collaboration, they're not interested in actually hearing from health professionals, or working with municipal leaders or working with folks in the community.

“This is a government that is obsessed with its own ideology.”

HERE ARE THE MAPS AND TABLES...

The map above created by Alberta Health uses colour coding to show varying rates of opioid poisoning related deaths in Edmonton neighbourhoods for the period of Jan. 1 to Oct. 31, 2021.

The table above compiled by Alberta Health lists opioid poisoning related deaths in Edmonton neighbourhoods from Jan. 1 to Oct. 31, 2021.

The map above created by Alberta Health uses colour coding to show varying rates of emergency responses to opioid related events in Edmonton neighbourhoods for the period of Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2021.

The table above compiled by Alberta Health lists emergency responses to opioid related events in Edmonton neighbourhoods for the period of Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2021.

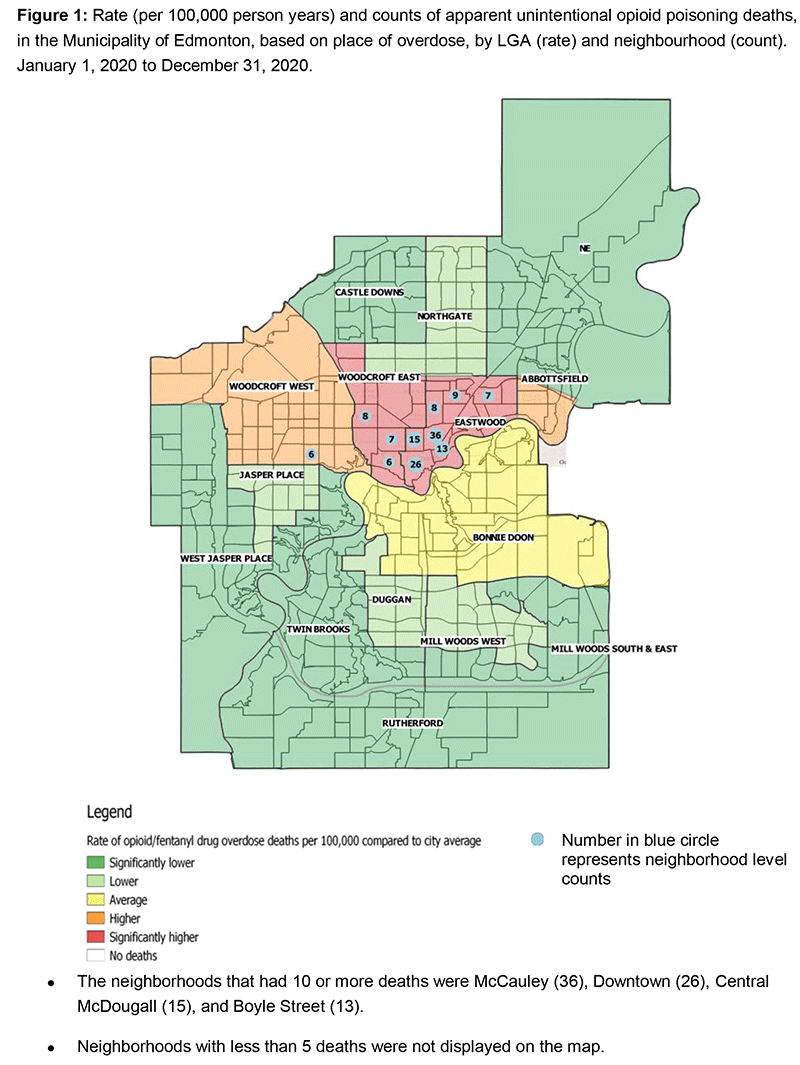

The map above created by Alberta Health uses colour coding to show varying rates of opioid poisoning related deaths in Edmonton neighbourhoods for the period of Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The table above compiled by Alberta Health lists opioid poisoning related deaths in Edmonton neighbourhoods from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020.

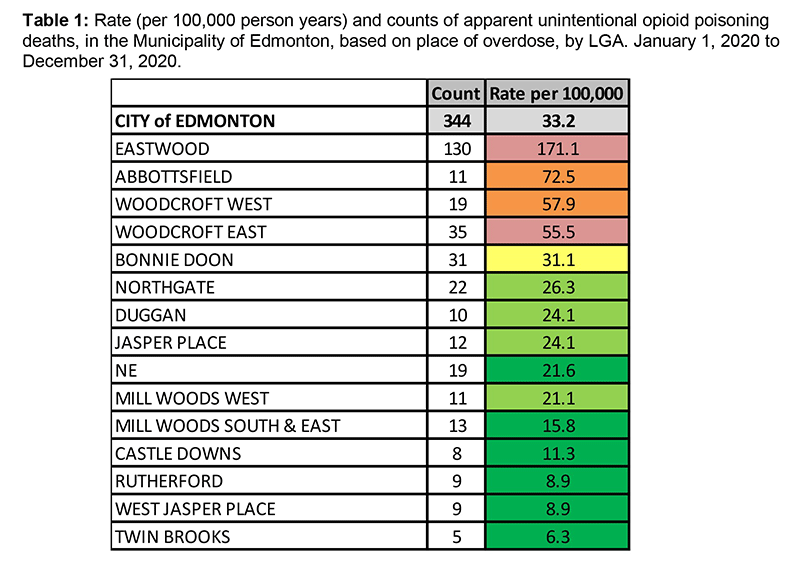

The map above created by Alberta Health uses colour coding to show varying rates of emergency responses to opioid related events in Edmonton neighbourhoods for the period of Jan.1 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The table above compiled by Alberta Health lists emergency responses to opioid related events in Edmonton neighbourhoods for the period of Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The maps and tables compared year over year show a sharp rise in opioid poisoning related deaths and emergency calls in Edmonton’s main inner-city areas of Eastwood, Woodcroft East and Woodcroft West. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: