In many ways, B.C.’s Gulf Islands are the tranquil, mossy oases mainlanders often imagine them to be. But they’re not immune to the kinds of debates that can divide societies — in fact, their self-contained natures can sometimes make disagreements more intense.

On Lasqueti Island, for example, you’re either a pro-sheeper or an anti-sheeper.

In mid-August, after speaking with over a dozen residents — and spotting several small herds of feral sheep from a distance — I find myself on the north end of the island feeding Rosemary, a previously feral sheep, a mix of grains from the palm of my hand.

It’s hot and smoky, and the tide is high in nearby Mud Bay. If I move too quickly, Rosemary shuffles backwards in the dry grass, her midsection hefting from side to side. This skittishness is understandable: marine biologist Anna Smith rescued Rosemary in mid-March after she was abandoned by her mother, one of the island’s feral sheep, at three days old.

In April, after rescuing Rosemary, Smith received a call about another ewe on the south end of the island that was shot with a crossbow. The crossbow bolt was still embedded in the sheep, which had recently given birth. Its lamb was small, weighing just four pounds, and it had no wool.

Smith extracted the bolt and rehabbed the ewe, whom she named Thyme. The lamb, Sage, seemed to thrive for a few months, before dying of what Smith suspects was a selenium deficiency resulting from being born prematurely.

Depending on who you talk to, the feral sheep population is either the gem of Lasqueti Island or a problem to be solved. Or perhaps that’s oversimplifying it.

Many islanders harbour both an affinity for the sheep and a desire to ensure that their herbivory — consumption of both wild and cultivated plants and grasses — doesn’t have too deleterious an impact on local wildflowers, food gardens and the forest’s understory.

Right now, as the island updates its official community plan, the sheep are also a lightning rod for controversy.

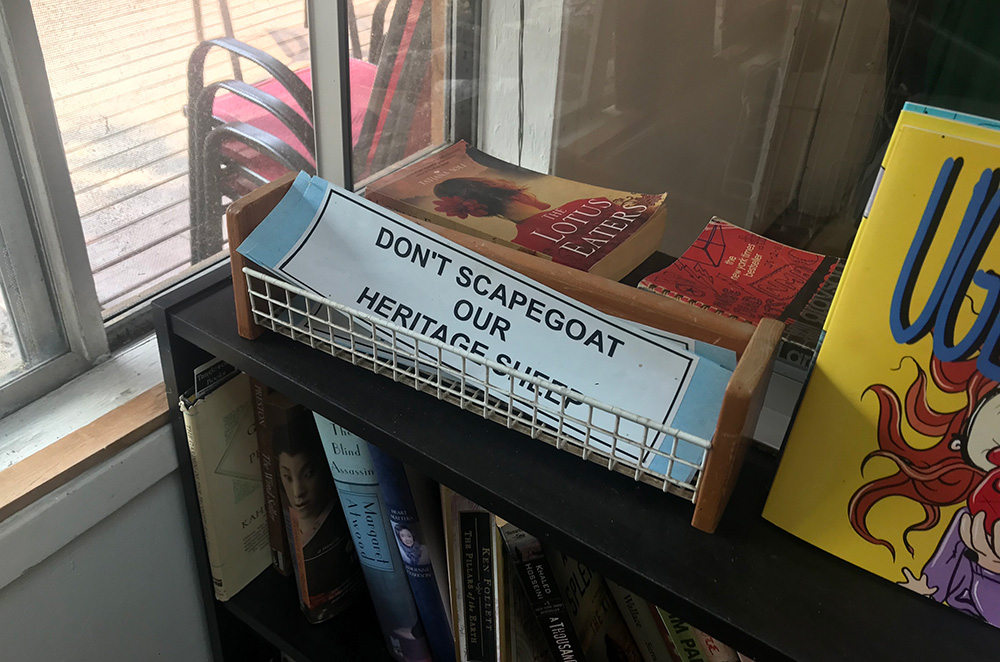

The pro-sheepers, as they refer to themselves, would prefer to maintain an existing objective of the plan: “to preserve and support balanced control of the local feral/heritage sheep which are a valued part of the community and its history.”

Their opposition — colloquially referred to, maybe unfairly, as “anti-sheepers” — have argued that this wording needs to be updated to reflect that “heritage” has specific, defined meanings and that preserving the sheep as is may mean sacrificing other flora and fauna.

In January 2020, after 27 meetings and seven public forums, the island’s Official Community Plan Review Steering Committee made a series of recommendations for updates. Among them was to edit the existing wording about sheep, so that it referred to them as an “exotic species” rather than a “feral/heritage” one, and to “minimize the impacts of invasive exotic species on native fauna and flora.”

For some anti-sheepers, this language offered a functioning compromise. But to most of the pro-sheepers, it signalled a desire to eliminate their beloved feral flocks from the island.

Functionally, the wording change would not have altered much. The island comprises mostly private land, and residents are free to do more or less as they wish with sheep that wander onto their property. Symbolically, though — even though most anti-sheepers say they wish to reduce the sheep population, not eradicate it — pro-sheepers felt the change would be the beginning of a slippery slope that could lead to more fences, less fondness, and, ultimately, fewer and fewer sheep.

‘They’re so happy to be alive’

The first sheep probably arrived on Lasqueti, a small island nestled in the Strait of Georgia, in the late 1800s. According to Elda Copley Mason’s book, Lasqueti Island: History and Memory, Albion George Tranfield arrived with sheep in tow in the early 1860s. Tranfield, Mason writes, “made regular trips to dispose of the mutton in his Nanaimo meat markets.”

A land surveyor visited in 1875 and found two settlers on the island — Tranfield, and another man named Captain Pearse. Both men owned about 200 sheep each.

Pro-sheepers tend to believe that the feral sheep are related to these sheep. An unsubstantiated rumour contends they arrived with the first Spanish explorers, those who renamed the island Lasqueti in the late 18th century. Others believe they were let loose later, maybe in the 1930s.

Another point of disagreement relates to how many feral sheep live on the island — anywhere from 300 to 1,000, according to the Lasquetians I interviewed.

In February 2015, teachers, students and volunteers from False Bay Elementary School on the island did a sheep count. Andrew Fall, a qathet regional director who’s also an adjunct professor in the School of Resource and Environmental Management at Simon Fraser University, helped design the study. It wasn’t a proper survey, Fall says, but it allowed them to come up with a low estimate of 259 adults and 81 lambs.

Fall keeps his own sheep: a rare heritage breed called Soay, originally from the St. Kilda archipelago in Scotland. (His work to preserve this breed colours his perception about whether Lasqueti’s feral sheep should be called “heritage,” as it’s impossible to know if they are a heritage breed without doing a full DNA analysis.)

Fall estimates Lasqueti to be home to about 400 feral sheep. This means that the island, with just under 400 year-round residents, is home to more sheep than humans on any given rainy November day.

“Have you ever watched lambs?” Tom Weinerth, a pro-sheeper who moved to Lasqueti in 1970, asks me over the phone. “I call it popcorn. All of a sudden, one of them will just pop into the air, and then all the other ones around, they’ll just start popping up. They’re so happy to be alive.”

In the winter, Weinerth supplements the sheep’s diets with grain. This past winter, he and a neighbour nursed a sheep who’d injured her leg. He enjoys seeing them gambolling by on his property.

Weinerth, a spokesperson for a pro-sheep delegation to a Local Trust Committee meeting in April, says the wording in the current community plan is already a compromise — one the community arrived at 20 years ago, the last time everyone debated the worth and place of sheep on the island.

If people want to move to an island with pristine old growth, Weinerth says, they should choose another island. Why move to one with sheep if you don’t like sheep?

An exotic species, and a source of sustenance

Lasqueti, which is located on the traditional territories of the Tla’amin Nation, as well as several other Coast Salish nations, might be the gulfiest of the Gulf Islands. It is, as the CBC puts it, a "counter-culture enclave."

Or, as one accurate if overly bewildered Global News documentary begins: “Imagine an island so secluded there’s no power, no paved roads and no plumbing in most cases either.”

Residents of the island, many of whom arrived in the 1970s (or who come looking for what settlers were seeking in the 1970s), have worked to ensure that the island’s ferry is passenger-only, that the roads remain gravel and that land can’t be subdivided smaller than 10 acres.

To the Global filmmakers, these rules enshrine a hippie-ish, throwback style of life. And maybe they do, in part. But they also exist, as someone ventured at a recent Local Trust Committee meeting, to keep “rich people” — people who might turn up their noses at outhouses and a lack of steady electricity and choose to spend their vacation house money somewhere else — away.

While the 2016 census doesn’t share information about residents’ income levels, a recent community well-being survey found that around 45 per cent of respondents from Lasqueti, compared with 20 per cent from the region as a whole, had household incomes between $10,000 and $29,999 per year.

These modest means point to feral flocks having added value. This is something the suggested wording for the new community plan recognized, saying the “exotic species” “may have value to the community as a source of local food.”

Gail Fleming, who moved to Lasqueti 42 years ago, chose the island in part because food sources were plentiful.

“There was salmon, there was rockfish, clams, oysters, wild berries, mushrooms, abandoned orchards and sheep — and even free-range cows at one point,” she says.

Forty years later, much has changed. The Salish Sea is becoming too acidic for oysters, salmon are endangered, and many of the orchards she used to access have been abandoned or taken over by people who have not kept them up. But the sheep are still there.

“Seldom a long period of time goes by somebody doesn’t show up at the door and say, ‘I got a sheep today,’ and hands me a package of lamb,” Fleming says.

And she cares more about food security than the wildflowers the sheep are eating. “I’ve never been to a wildflower barbecue,” she says.

Wendy Schneible, vice-president of the Lasqueti Island Nature Conservancy, has been on the island for 47 years. She arrived in her 20s as a back-to-the-lander. At first, she lived in a teepee and wanted to be fully self-sufficient. Soon, reality set in: they all needed supplies, like kerosene for their lamps, that they couldn’t produce themselves.

In addition to feral sheep, there were free-ranging cows and horses on the island in the ’70s. Some of the horses were cared for and others roamed. One day, Schneible returned to find devastation at her teepee — a horse had busted it open, knocked over jars of oats and eaten them.

Schneible, who disagrees with calling the sheep “heritage,” is OK with the other aspects of the old community plan wording that calls for “balanced control” of the sheep population — the way things are handled currently doesn’t actually control the sheep, or balance their needs with those of native plants and trees, however, and the status quo needs to change.

“There is no ‘balance,’” she said. “There is no ‘control.’ They want to maintain the status quo, which isn’t what the actual wording says.”

At Osland Nature Reserve, which covers about 60 acres, Schneible shows me two fenced “exclosures” LINC has set up to keep feral sheep (and native deer) out. Outside the fences, sheep and deer paths crisscross the mossy, rocky outcrops. The bottom branches of the cedars have been stripped of greenery, and some daring sheep or deer have even taken nibbles of stinging nettles and thistles.

Inside the four-year-old exclosures, which abut a marsh, the grass is longer and the plants more abundant and varied. The goal of the exclosures is to track the impacts of herbivory and the process of recovery and restoration.

LINC has no official mandate about the sheep, Schneible tells me later, and the organization has no desire to either eliminate or take responsibility for them. Her opinion about the community plan wording is hers as an individual, rather than a representative of LINC.

Osland’s circumstances are mirrored on the south end of the island, where Ken Lertzman and Dana Lepofsky live. Lertzman, a member of LINC and a professor emeritus of forest ecology and management at Simon Fraser University, and Lepofsky, a professor of archaeology at SFU, have both written letters in support of changing the community plan’s wording around sheep.

They’ve fenced off a small part of the property they’ve shared with several other families since 1989. Outside of the fence, the property has been denuded of most greenery other than moss. Even the swordfern is chewed to its base, which, Lertzman says, is “not good eating."

Inside the fence, Lertzman points out plants that have regained their footing after being kept from sheep and deer: starflower, salal, huckleberries, salmon berries, elderberries, maple trees and deer fern.

As a forest ecologist, Lertzman’s educated guess is that tree species such as western red cedar have not regenerated effectively after land clearing on some parts of the island in part because of artificially high levels of “browsing” — in other words, because sheep and deer have eaten young shoots and trees.

To really understand the impacts of sheep on the forests, and the flora and fauna they support, Lertzman says the island needs to gather solid data.

The exclosures LINC has created at Osland, and some new exclosures they have planned for the Mount Trematon Nature Reserve, will allow them to gather information about the impacts of herbivory. Other important data to gather could include DNA analyses of the sheep population, a more accurate sheep count, and a survey of their health.

Many people I spoke with who appreciated the sheep but were worried about their ecological impacts also tended to worry that the sheep probably had parasites, went hungry in the winter, and needed shearing. Gathering data could provide information about these issues.

Anna Smith, the biologist who took in Rosemary, Thyme and Sage, also thinks it’s a good idea to properly assess the island’s sheep population, their genetic variation and their herd ranges.

She agrees, too, with investigating the impact of grazing and browsing on the island’s ecosystems, but she cautions that some differences people see on the north end of the island, where there are fewer sheep, and the south end of the island, where there are more sheep, may be due to differences in micro-climates rather than simply being a result of their presence.

Most pro-sheepers also wouldn’t mind gathering data about the sheep’s numbers, their ranges and their genetics. In fact, many believe that DNA testing could support the idea that Lasqueti’s sheep — which are not susceptible, for example, to scrapie, a fatal disease similar to mad cow — are a hardy, heritage sort of stock. The sheep wouldn’t have survived a century on the island if they were not relatively well and thriving, pro-sheepers say.

But they don’t necessarily trust LINC — a group that contains members many of them perceive as “anti-sheep” — to facilitate research.

When I first stumbled across Lasqueti’s feral sheep, I’d wondered why I, like many settlers, found something about them inherently fascinating. I’d set my assumptions aside when I found out about lamb barbecues — but revisiting the question, the fact the sheep are a food source doesn’t cover all the bases.

For a lot of pro-sheep Lasquetians, it might be something about their previous domestication that provides a draw. This domestication signals a symbolic proximity to humans, or maybe, much like the aims and goals of the back-to-the-land movement, the sheep used to lead penned-in, circumscribed lives and now are free.

(My hunch about Tom Weinerth is different. Though he’s eaten lamb barbecue in the past, he’s now a vegetarian, and I get the sense from talking to him that the sheep are his treasured friends.)

“They’re almost like the Lasqueti mascot,” Schneible offers.

“It is in many ways much more of a social issue than a biological issue,” Lertzman says, mulling over why the issue of sheep is dividing the community — and why they hold such a strong draw for some Lasquetians. “The biological aspect is straightforward, but the social aspect of it is much more complex.”

To Lepofsky, who joins our conversation midway through, a major problem with the current community plan wording is that it communicates a short-sighted view of heritage. In B.C., she says, much of the heritage protection has to do with colonial heritage.

“I have a deeper interest in longer-term heritage and connections to place,” she says. “When I think of heritage, I think instead about Indigenous heritage and that of the heritage ecosystems that Indigenous peoples were and are a part of.”

A ewe-turn?

On Aug. 13, the island’s trustees, the chair of the Islands Trust Council, some Islands Trust staff, Andrew Fall and about 12 community members met outside Lasqueti Island’s Judith Fisher Centre in the growing heat of one of coastal B.C.’s increasingly frequent heat waves.

The previous day, a LINC member had told me they expected that most of the people in attendance would be pro-sheepers. As the meeting progressed, it became clear they’d guessed right.

The process leading to the decision to change the community plan language about sheep was called Orwellian (both 1984 and Animal Farm were referenced), there was heckling, and there was someone calling, “hear! hear!” after another person — who first criticized a bylaw prohibiting yacht clubs from installing floats and other amenities — said the sheep are important to food security and he’d been eating them for 70 years.

Trustee Tim Peterson suggested that council rescind the second reading of the community plan in order to revert to the original language about sheep. The chair of the Islands Trust Council, Peter Luckham, weighed the pros and cons of Peterson’s suggestion.

In the end, they voted to rescind the second reading, revert the wording and pass the second reading again.

The community members in attendance seemed relieved. For now, at least as far as the community plan is concerned, the sheep will remain “heritage” sheep, a “valued part of the community and its history.”

As the meeting ended, Weinerth, who’d been one of the more vocal attendees, chatted happily with other community members. “There’s still some touching up to do,” he told me later, on the phone. “But I’m satisfied.”

Smith believes the trustees made the right decision. “It’s a good thing,” she said. “It’s really about the perception.”

The day after the meeting, I bike to Fall’s farm. As we feed the female Soay sheep a mix of a little grain pellet, which they like, and barley, which they dislike, I recall a conversation I had with Fall before I came to the island.

The feral sheep, he told me, come under the jurisdiction of the province, so any policy contained in the community plan about them will be an advocacy policy — in other words, like Smith noted, a policy that affects perception, rather than one that comes with any power to enforce anything.

Regardless of what happens with the community plan wording, Fall says, people will still be able to harvest the sheep for food or take them in to provide care if they get sick or injured.

Though the wording feels important to many islanders, whatever wording is settled on will not address the underlying dispute. Only an interest-based community process — where Lasquetians could come together to share their values and concerns — has any chance of resolving this issue, Fall says.

“The fabric that holds a community together is more easily torn than woven,” he says. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: