It was already a race against time.

Government contractors have been working since early this year to clear a huge Fraser River rockslide north of Lillooet which continues to bar passage to migrating Fraser salmon. The work must also be completed before the spring freshet comes, which means that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had mandated the work to be done by the end of March.

That was then.

When COVID-19 became an issue, the new question became whether a workforce would continue to work at the site at all. If the rock cannot be blasted and cleared adequately, experts fear endangered stocks like early Stuart sockeye, brutally depressed for years, could disappear altogether.

The pandemic has not yet halted efforts, The Tyee has learned. But on March 25, a week before river work was supposed to be wrapped up, FOC confirmed that the natural fish passage will not be restored in time for the 2020 Fraser salmon migration.

That means that many Fraser salmon returning to the river this year will have to rely on a series of “contingency” measures including a repeat of the heroic but ineffectual 2019 efforts that saw salmon netted and transported to the other side of the obstruction. Many of these fish did not survive to spawn.

“People were hoping we’d have a late freshet, and we’d be able to remove so much rock that we will get the natural [fish] passage again, but I think that was wishful thinking,” Gwil Roberts FOC’s director of Big Bar Landslide Response told the Tyee. “We can remove some percentage of the [rock], but there will still be too much material in the water to let fish to pass on their own.”

Roberts added that COVID-19 has not caused significant delays at the work site and that government remains committed to restoring natural fish passage on the Fraser River — a goal that will likely take years to achieve.

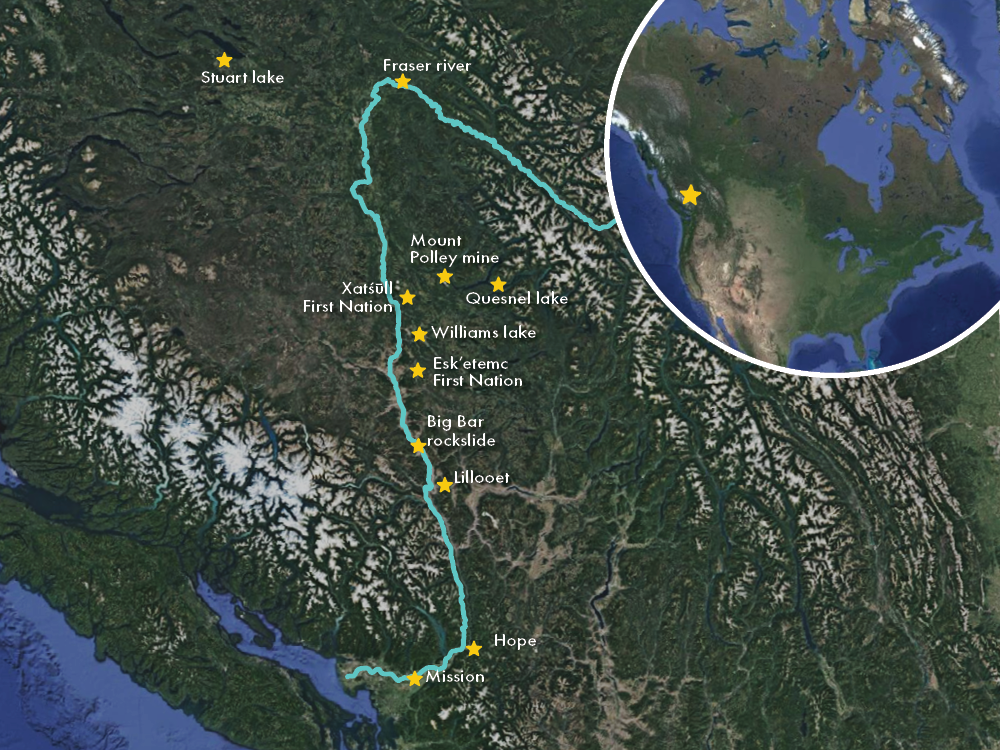

Big Bar first came to national attention in late June 2019, right around the time Esk'etemc First Nation Chief Fred Robbins stood on a fishing platform above the Fraser River, poised to harvest chinook salmon that would never arrive.

“We fished from 7 p.m. to 2 a.m. without hitting anything for four nights in a row, and that’s when I clued in that there must be something going on,” says Robbins, a second-term chief of this remote First Nation, located about 40 kilometres south of Williams Lake, and numbering about 1,000 members.

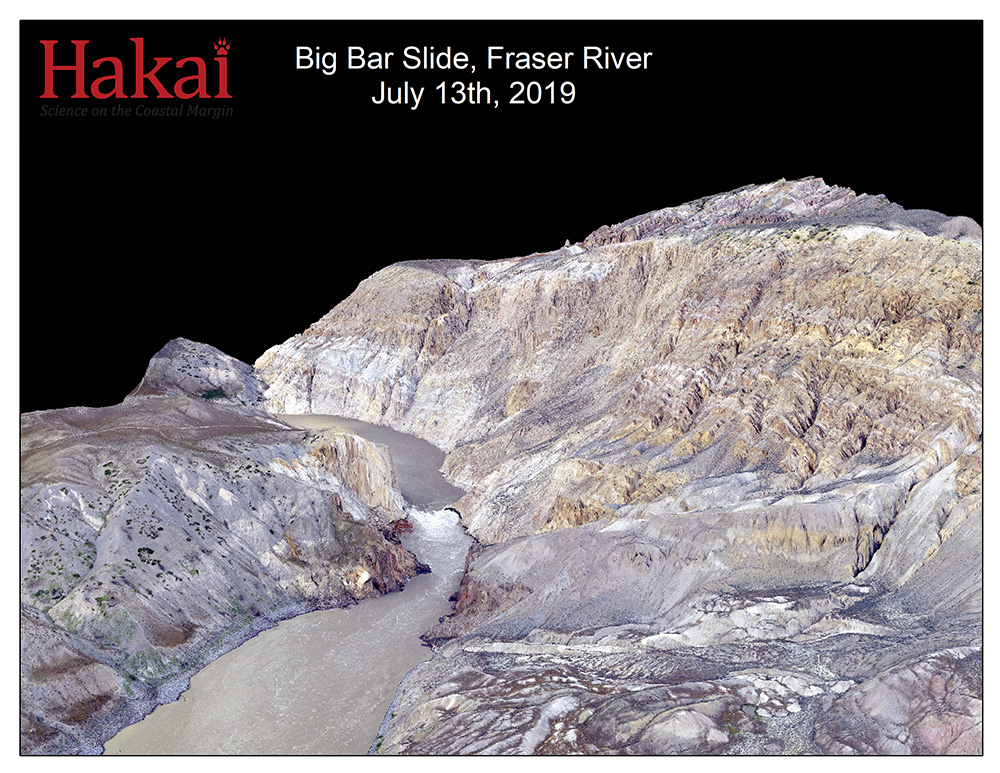

Little did he know at the time, a rockslide at Big Bar about 65 kilometres north of Lillooet had deposited 1,800 metric tons of rock into a narrow canyon about 15 kilometres below his family fishing spot, creating a long stretch of rapids and a five-metre high waterfall, barring the passage of salmon migrating to the central and upper Fraser watershed.

For the more than 20 First Nations living above Big Bar, the disaster exacerbated an already desperate situation. In recent years, all six species of Fraser salmon have been clobbered by pollution, habitat destruction, poor marine survival, the close proximity of salmon farms, overfishing, climate change impacts and much more. And now a wall of rock suddenly slammed into place just as millions of highly-stressed fish were coming home.

Casualties were high. Out of a projected return of about 4.8 million sockeye salmon returning to the Fraser, Fisheries and Oceans Canada now estimates just over 300,000 survived to spawn. Multiple runs of endangered and threatened Fraser chinook, a primary food source for southern resident killer whales, have not fared much better.

The sole upside of the disaster is that it’s shining a new light on the gauntlet Fraser salmon must run to get back to their natal streams to spawn — the subject of an accompanying piece published today on The Tyee. The rockslide was an act of nature that with engineering expertise can eventually be fixed. What will prove much harder is to save Fraser salmon from the trajectory of decline they were already on before the rockslide even happened.

Bev Sellars, the former long-time chief of the Xat’sull (Soda Creek) First Nation based in Williams Lake, says that she and many others have been warning FOC since the 1970s that Fraser salmon are in trouble. She’s frustrated that the warnings of Indigenous people, particularly on the upper Fraser, have not been translated into FOC action.

“If there’s any hope for [Fraser] salmon, the fish have to be put front and forward, and everything they need to survive needs to be looked at,” she says. “If things don’t change, salmon are already in trouble, and in a few years, they are going to be gone completely.”

More than eight months after FOC first learned of the slide, the impasse at Big Bar remains. It’s now a race against time to remove as much of the rock as possible before the freshet and the late spring return of salmon. One theory is the rockslide was caused by heavy rains during the fall of 2018, followed by a deep freeze and rapid thawing, which destabilized the Big Bar canyon walls.

Jeremy Venditti, a professor at Simon Fraser University’s School of Environmental Science and department of geography, who has studied the Big Bar area in detail, thinks it’s more likely that seismic activity toppled a huge body of weakened, vertically-standing rock.

He says the slide was plain bad luck: it happened at the worst possible place during a low-water year, landing on a pre-existing mass of bedrock, which held the rockfall in place. Normally the rocks would have been flushed by the force of the river at the peak of a freshet flow, but the 2019 freshet was also much smaller than average.

Based on satellite photos analysis, Venditti has estimated that the rock slide occurred around Nov. 1, 2018 — more than seven months before FOC knew about the slide. Even then, it was a local rancher that first detected the slide. By the time FOC was informed, the date was June 23 and less than a month before endangered Stuart Lake sockeye would nose up to rocks at Big Bar.

“I think everyone involved is realizing the river needs to be monitored for rockslide risk, so everyone does not get surprised again,” says Venditti.

Once alerted, FOC sprang into action. “We investigated the site 48 hours later [after June 23] and a Big Bar incident command post was set up in under a week,” says an FOC spokesperson. Drawing on the expertise of both the province and local First Nations, efforts were made to create passageways through for the fish. By July 20, stranded salmon were being caught in beach seine nets and ferried to the other side by helicopter.

In late 2019, FOC contracted the global firm Peter Kiewit to lead the engineering work to blast and remove the huge amounts of rock at Big Bar, a $17 million project. Kiewit blasted the “East Toe” of the rockslide on Feb. 18, which shattered rock in the riverbed and widened the channel. A second blast was planned for early March, but has not happened as of this writing.

FOC’s Roberts who manages work at the site, says that contractor Kiewit was not hired to restore fish passage per se, but to remove as much rock from the riverbed as possible before the freshet. He says this included the time-consuming construction of a new river access road over treacherous terrain. FOC planned for work at Big Bar to be wrapped up by the end of last month, but crews are working into April, in a race to get as much rock out of the river as possible before freshet.

Chief Fred Robbins is critical of the 2019 response. For one thing, he says FOC could have installed a novel salmon recovery system called a Whooshh Fish Transport System, also known as a "salmon cannon” — a giant suction hose that can suck the salmon right past an obstruction and out the other side with minimal harm or stress. It would have taken time and money, including the need for road access so the system could be set up, but he thinks it could, and should have been done. (Watch how such a cannon works in the video below.)

Instead salmon were caught by beach seine nets and moved by helicopter to the other side. Of the 26,000 early Stuart sockeye that entered the Fraser River early last summer, 89 survived to spawn. “They were annihilated,” says Robbins of the run.

Early Stuarts are one of many Fraser River salmon populations that were in trouble before the slide. At least seven sockeye populations that return each year to points above Big Bar have been designated either endangered or of special concern — and many coho and chinook runs that now return to the Fraser are endangered or threatened.

Greg Taylor, fisheries advisor with Watershed Watch Salmon Society, says migrating sockeye and chinook salmon took the disproportionate brunt of the river blockage: 100 per cent of the early Stuarts, and about 60 per cent of the early summer and summer sockeye returning to the Fraser last year were trying to migrate past this rockslide. The future viability of early Stuart sockeye, Taylor says, will depend on whether there is still a significant obstruction at Big Bar by the time mid-July rolls along.

Robbins is worried about the chinook his family intercepts each year as they ascend the Fraser on their way to the Quesnel River system. These same fish must also pass through the same waters affected by the 2014 Mount Polley mine disaster, which dumped 25 million cubic metres of mine tailings into Quesnel Lake, which drains into the Fraser. To this day, no one knows for sure what the impact of this great toxic plume has been on the Quesnel system and the downstream Fraser.

Unable to catch chinook at all last year, Robbins drove almost four hours from Williams Lake to Lillooet to pick up 17 fish, which he distributed to community elders; he later picked up about 70 fish from another First Nation near Adams Lake, but that was it.

“It’s been a real struggle,” he says of the loss of food fish. “Normally when you drive into my community in the summer, coming [southwards] from Williams Lake you drive into a valley where smoke is rising from all these little smokehouses. This past year, none of those little sheds were used at all.”

The survival of this year’s salmon returning to the Fraser will rely on at least three “contingency” plans.

FOC’s Roberts says contractors have been creating a channel on the west side of the river by placing rocks and boulders that they hope will help fish to battle the strong flows of the river.

They will also employ a similar “trap and transport” scheme as last year, netting fish and transporting them to a point above the rockslide site, for release.

And finally, FOC is already planning to employ a “pneumonic fish pump” — something similar in principle to the “fish cannon” recommended by Chief Robbins. “This year we’re doing everything we can to try to make sure that the vast majority of fish are able to pass,” said Roberts.

No matter what happens moving forward, Aaron Hill has a single warning in the wake of the rockslide. With the huge decline of stocks, and now last year’s disaster, the Executive Director of Watershed Watch Salmon Society says there is growing pressure to ramp up hatchery production to make up for lost natural production. “It’s a terrible idea,” he says.

Hatchery fish, Hill explains, will flood the ocean with more young salmon which compete with wild fish for limited food, drawing more fishing pressure, resulting in the incidental catch of endangered wild fish as they swim amid big numbers of hatchery fish. And it will cost a lot of money. “Hatcheries are very expensive and it’s money that could be put into habitat restoration and monitoring."

Former federal NDP fisheries critic Fin Donnelly concurs. He is now rallying government, First Nations, NGOs, labour and the private sector to raise $500 million to restore salmon habitat and “climate proof” the entire 21 million-hectare Fraser watershed (more than a quarter of B.C.) over the coming decades.

For Donnelly, it’s a generational project. Long before he was ever elected, Donnelly made a name for himself as an advocate for salmon and the many interconnected watersheds of the Fraser River. On two separate occasions, he imitated a giant ocean-bound Fraser salmon and swam the entire 1,300 kilometre river from the Rocky Mountains to Musqueam territory on the tip of Vancouver.

Recently retired from politics, Donnelly says the most immediate priority is to restore passage at Big Bar. Then there’s all the “low-hanging fruit” of protecting the most productive salmon habitat — including the salmon and sturgeon nursery islands between Hope and Mission. Commercial fishing must shift to selective methods, he says, including replacing gillnets on the lower river with pound nets, fish wheels and traps.

Over the next five to 15 years, hundreds of side channels and sloughs in the Fraser valley cut off by old irrigation works could be reconnected to the river. Fraser-flowing wastewater treatment plants could be moved to cleaner technology, salmon habitat restored in all regions of the Fraser, and salmon farms transitioned to closed containment or land-based aquaculture.

There was hope for the latter during last year’s election, when the federal Liberals (as well as the NDP and Greens) campaigned on a promise to phase out open net-pen salmon farming by 2025. The Liberals have since backpedaled, confirming now that 2025 is the deadline for a plan only, not the actual transition.

Sports and commercial fishing is also an issue. Since last October, British Columbia salmon fisheries no longer carry Marine Stewardship Council certification (the MSC is an international, independent non-profit organization that sets a standard for sustainable fishing) — a major international embarrassment for a fishing industry that projects an image of sustainability to the world. Alaskan salmon fisheries, by contrast, retain this MSC certification.

MSC concerns with B.C. included deficiencies in monitoring (e.g., knowing how many fish return to their natal streams), unclear hatchery-wild fish interactions, and insufficient information about the fish being caught accidentally when specific salmon are targeted. “This was all really basic, fish management 101 stuff,” says Taylor. “And they couldn’t do it."

Asked if the rockslide will prompt new sports and commercial fishing closures in the 2020/21 fishing year, FOC confirmed it is “currently consulting on possible management measures” for this coming year, but would not provide specifics.

Richard Holmes, a fisheries biologist who lives near Quesnel Lake and has worked with many First Nations that rely on Fraser salmon, adds that any future FOC salmon management overhaul — which he deems necessary — must include working closer with Indigenous Peoples on the central and upper watershed.

"FOC needs to work with upper Fraser River First Nations in co-designing, co-planning and co-implementing a response to low [spawning success] and the Big Bar slide, to not only conserve but to enhance upper Fraser salmon stocks. These great runs have been decimated by FOC neglect for far too long."

Last summer, Bev Sellars’ home community near Williams Lake caught no salmon at all, other than three fish provided to each household by Chilliwack-area fishermen. She admits to being cynical that a salmon management overhaul will happen any time soon. In her view, this would mean a big change in priorities for two levels of government. “They would need to put the environment ahead of money, and the natural economy ahead of the monetary economy.”

Unpacking this management obstacle to a sustainable fishery may prove far more difficult than blasting away fallen rocks. In the meantime, the Fraser River remains a deadly gauntlet for salmon who once teemed in its waters.

See each threat in that deadly gauntlet for Fraser River salmon in this accompanying story today.

This story was produced in partnership with the Hakai Institute’s Storylab initiative. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Food, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: