At a recent event on W̱SÁNEĆ territory, various speakers insisted that despite what you may have heard, reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples is not dead, that it can’t be, that it’s just getting started.

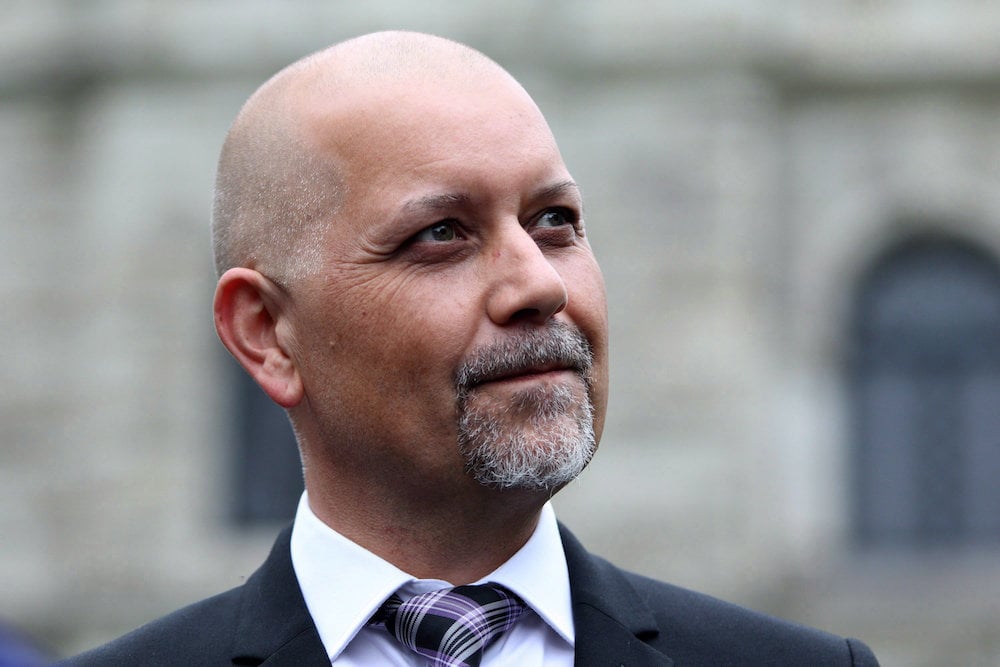

First on that tack was Adam Olsen, the MLA for Saanich North and the Islands and a member of the Tsartlip First Nation.

“The last few weeks have been difficult,” he acknowledged. “I think they’ve been difficult for a lot of people in this country and a lot of people in this province.”

As Olsen spoke, federal and provincial ministers were arriving in Smithers to meet with Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs opposed to a natural gas pipeline that Coastal GasLink is building on their traditional territory with provincial and federal government approval.

The project has been a flashpoint for Wet’suwet’en supporters whose actions across the country have included blockading rail lines, shutting major roads, closing government offices and preventing entry to the B.C. legislature.

The conflict had in many cases brought out the worst in people, exposing racist attitudes, from white supremacists threatening to use force to clear blockades to some mainstream politicians supporting vigilante threats.

That weekend, Anishinaabe author Tanya Talaga wrote in the Globe and Mail, “The fact is, reconciliation never truly existed. It’s always been a slogan uttered by politicians who... were trying to seem progressive, show that they care, make things right.”

And Pam Palmater, a Mi’kmaq lawyer and Ryerson University professor and chair in Indigenous governance, wrote that ‘reconciliation’ is a new name for the same old Canadian policy. “The goal is still the same: to clear the lands of Indigenous peoples in order to bolster settlement and extraction of resources.”

On Twitter, #ReconciliationIsDead has become a frequently used hashtag along with #ShutDownCanada and #WetsuwetenSolidarity.

Olsen described recent events as “some very substantial stumbling, maybe fumbling,” but was unwilling to agree with people pronouncing reconciliation dead on arrival.

“I must push back on that every time I see it, because reconciliation must continue in this country,” he said, adding that in these difficult times, it’s important to embrace reconciliation even more strongly.

Olsen spoke as part of the Victoria Urban Reconciliation Dialogue, a by-invitation event hosted through the Victoria Native Friendship Centre with support from federal, provincial, regional and municipal governments.

Around 150 people attended the gathering on the Saanich Fairgrounds, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members, representatives of local First Nations, Métis groups, various levels of government, community social service providers, police departments, and arts organizations.

As part of a panel discussion, Ry Moran, the director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation and a member of the Red River Métis, picked up Olsen’s theme, saying that as long as there’s at least one person working to further reconciliation, it can’t be dead.

“There are millions of people who are committed to reconciliation fundamentally,” he said.

Moran said it’s important to keep sharing stories of injustice and to do it in a way that connects emotionally so that people can feel the injustice. “When you lay the atrocities of this country bare, and do it in a good way, the truth is irrefutable.”

Author Monique Gray Smith, who is of Cree, Lakota and Scottish descent, said the actions across the country are taking an issue that was long invisible to many people and making it visible.

“It feels like something is different this time,” she said, noting that the frustration young people have with elected leaders is understandable and that it’s okay to have conflict and work it through. “Love is medicine, and this country needs a whole lot of medicine right now.”

Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps talked about the need for reconciliation to be place-based and said that she sees the role for settlers like herself as listening, learning and acknowledging hard truths. “What does it mean to have moved into somebody’s living room and never left? How do you reconcile that?”

Several speakers through the two days of the event made reference to hard conversations and the need to have them, though for the most part those conversations were left for another day.

Small group discussions were wide ranging and open ended.

In a group on Defining the Road Ahead, everyone had a turn to introduce themselves and give their opening thoughts. Some talked about the exclusion, discrimination and racism they’d experienced and about the continued legacies of residential schools, the Sixties Scoop and the theft of land. Self-described settlers and Indigenous people from other territories expressed gratitude to be uninvited guests on beautiful W̱SÁNEĆ or Lekwungen territory.

In a discussion on Measuring Reconciliation, questions came up about what to measure and how. Is it about the resources that governments put in, what public opinion polls say about shifting attitudes, or progress on the social determinants of health? How do we avoid reconciliation becoming a box-ticking exercise, an empty process?

The decolonization and Indigenization session included talk about the need to rectify power imbalances and to allow for more control over the resources that impact people, particularly keeping in mind that nearly 80 per cent of Indigenous people don’t live on reserves. As one person put it, you can’t “reconcile” when a power relationship continues.

In none of the groups did we arrive at answers, and that was fine, the main point being to start a conversation and build relationships.

As Gray Smith had put it, when people ask her what they can do, “Sometimes I say, ‘How could you be?’ In the listening, you help to put things right.”

Swil Kanim, a musician, storyteller and member of the Lummi Nation, was similarly reassuring that sometimes showing up and coming to the conversation with love is enough. “It doesn’t take much to change the world.”

Or as Stuart Gale from the provincial Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation ministry put it, “Is reconciliation dead? No. Reconciliation is about people coming together and having conversations.”

To reconcile can mean to “make friendly again after an estrangement” or to “make compatible,” but it can also mean to “make acquiescent or contentedly submissive to something disagreeable or unwelcome.”

The goals need to be ambitious. Progress will include paying close attention to measures of social and health equity, which are closely tied to self-determination, and finding just ways to settle land and title issues. As long as Indigenous people are less likely to graduate high school and more likely to be in jail or government foster care than others, for example, we’re not where we need to go.

In his remarks to open the dialogue, Olsen had called for patience. The current situation was generations in the making and healing will take time, he said. “If we are going to truly heal the past we can’t be set back, we must continue to move forward. We’re just starting on this process.”

Having grown up on the Tsartlip reserve, Olsen said, he’s well aware the problems are systemic and so he’s supportive of systemic solutions, like the legislation the province passed to work towards bringing B.C.’s laws in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“It starts to change the systems,” he said. “It starts to change the way we view the conversation that we’re going to be having going forward in the future, it starts to reframe it in the way that Indigenous people have a place at the table rather than being told how they’re going to be [represented].”

A couple nights later, at a separate event, the City of Victoria hosted some 400 people who turned up at the conference centre to talk about reconciliation, the fourth discussion in a series that’s been ongoing since last fall.

Many took the turn-out as an indication of the appetite that exists to continue the conversation and move forward together to get reconciliation through its infancy. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: