The head of an organization backing a court challenge that could reshape health care in Canada says it has become too expensive for regular people to be able to argue their cases in front of a judge.

“The cost is prohibitive for any individual Canadian to launch a case like this,” said Howard Anglin, the executive director of the Canadian Constitution Foundation. “It’s certainly not ideal. I do think it’s a problem an individual Canadian would find it beyond their means to litigate a constitutional case.”

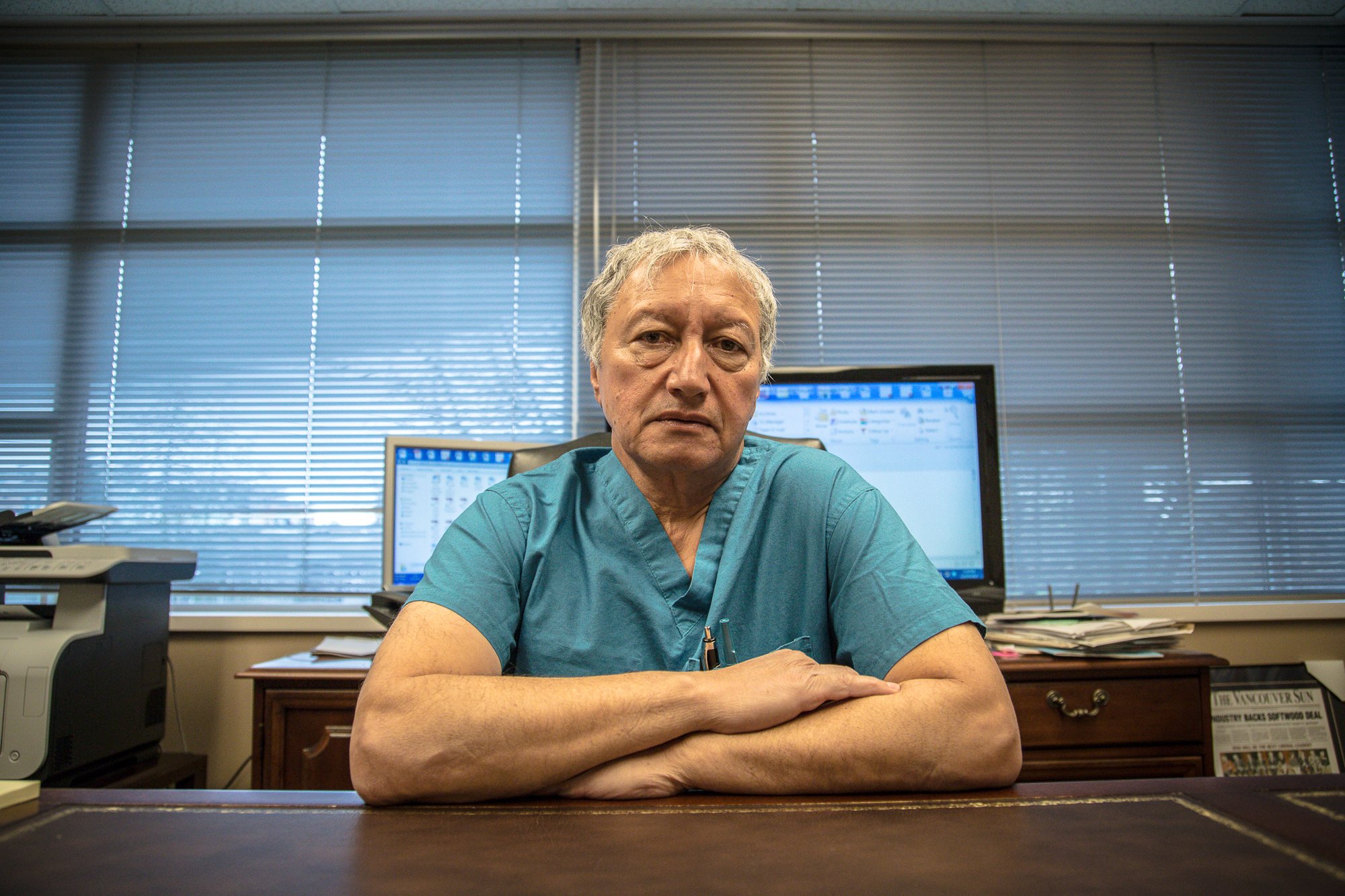

Vancouver doctor Brian Day has been the public face of the Cambie Surgeries Corporation’s challenge to sections of the Medicare Protection Act being heard in the B.C. Supreme Court. The trial began in September and is expected to continue until April.

The corporation is arguing that laws preventing patients from paying extra for speedier treatment violate their constitutional rights.

Day has been quoted saying he’s taken a $1-million mortgage out on the Cambie clinic to pay legal bills for the challenge. But when The Tyee asked him about the figure in September, he said fundraising was happening through the CCF’s Charter Health website.

Anglin said various contributors had initially supported Day’s battle, but the Canadian Constitution Foundation is now the main funder for the challenge, which has taken about six years to get to court.

“We raised quite a bit of money before the case started,” he said. “There’ve been a lot of delay tactics that have eaten up a lot of funding.”

Anglin said he was unsure what the CCF has spent. If it weren’t for lawyers working for reduced fees, it would have cost millions, he said. That would be out of reach for most individuals, and that’s not good for access to the justice system, he said.

Fighting the government

Defending against the challenge are three parts of the B.C. government: the Medical Services Commission, the health ministry and the Attorney General.

With a few exceptions, the Medicare Protection Act prohibits doctors from charging patients directly for services that are insured through the public system. The law says people should have “reasonable access” to care that is universal and unimpeded by user fees or extra billing.

In 2012, a B.C. Medical Services Commission audit stemming from a 2008 complaint found Cambie Surgeries Corporation and the closely related Specialist Referral Clinic (Vancouver) Inc. were guilty of extra billing on a “recurring basis” and had broken the act.

A health ministry spokesperson said Wednesday she couldn’t provide a figure Wednesday for the government’s anticipated spending on the case. In September, a ministry spokesperson said the government is committed to defending the Medicare Protection Act “and the benefits it safeguards for patients in this province” and would see the case through to its resolution.

Anglin said the province appears to have as many 20 lawyers working on the case. “Whatever it costs us in the end, it’s going to cost taxpayers a lot more on the government side,” he said.

The B.C. Health Coalition, part of a group participating as an intervener in the case to defend public health care, has previously said it was raising $550,000 to cover its legal costs.

Connections to Kochs, Harper

The CCF’s involvement has received little public attention, though the website Press Progress in September detailed some of the organization’s connections.

Linking to a CBC story, Press Progress said “The CCF has... received funding from and is a member of the Atlas Network, an international network of libertarian and Tea Party groups sharing information, resources and distributing funds.” It noted that donors to the network include the American oil tycoons Charles and David Koch.

Press Progress also highlighted Anglin’s background as the chief of staff to former Conservative cabinet minister Jason Kenney and as a staff member in the Prime Minister’s office under Stephen Harper.

Anglin, who was deputy chief of staff to Harper, has written about the experience for Policy Options, in a book review where he argues aides should be in the background lest they distract from the elected officials and the government’s policies.

Anglin became executive director of the CCF, which is headquartered in Alberta, this past July. He said his time in politics is not secret and helped him develop a thick skin and in some ways it led him to his current position.

“I took this position because politics spoils you,” he said. After being involved in interesting issues that have the potential to be transformative, he was less interested in returning to a private legal practice, he said. “I feel very fortunate to be doing what I’m doing.”

Other cases the organization has worked on involved civil forfeiture laws, freedom of speech and barriers to inter-provincial trade, he said. He acknowledges the CCF takes positions on cases that many libertarians would support, but he balks at being labelled. “Everybody hates labels and I’m no different.”

The Cambie case is a good fit for the organization, Anglin said. “It falls within our mandate to defend constitutional rights of Canadians,” he said.

The organization takes on a limited number of cases, not more than four or five at a time. “We try to choose ones with the broadest possible impact. This is that kind of case potentially, we think.”

The challenge builds on the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the 2005 Chaoulli case that overturned Quebec’s ban on selling private insurance to cover medically necessary care, a ruling that only applied in Quebec, Anglin said. “We think it’s a case not only whose time has come but is probably overdue given the Supreme Court ruling in Chaoulli was more than a decade ago.”

Outside of Quebec, there have been no significant changes to provincial health care systems in the wake of that ruling and it’s unfair to prevent patients on long waiting lists from taking steps to find the medical care they need, he said.

“There’s a growing recognition there are problems in the system,” he said. The government could eliminate wait lists through public health care, he said. “If that were happening, we wouldn’t be in court. We wouldn’t have a case.”

In B.C., private clinics have operated under NDP and BC Liberal governments since the late 1990s, Anglin said.

“There’s been a de facto private option in B.C. that doesn’t exist in other parts of Canada,” he said. “What we’re fighting for is to maintain the status quo, which is the operation of these clinics.”

The foundation wants doctors to be able to work in both the public and private systems, he said. Patients or their private insurance companies should not be blocked from paying for treatments that are covered under the public system, he said.

Like other participants in the challenge, Anglin expects the case will end up in the Supreme Court of Canada. “In some ways, this is just the rehearsal,” he said.

At this stage the goal is to get as much evidence on the record as possible, which can be influential as the case progresses to higher levels. “That’s why we’re not cutting corners,” Anglin said. “We’re going through the full exercise and the Crown is as well.” ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: