[Editor’s note: On March 12, 2014 the Canadian flag was lowered in Kabul, marking the end of the longest-running combat mission in Canadian history. More than 40,000 men and women served, 158 died. The number injured depends on how you define the term. This three-part series profiles three veterans seeking, in their own ways, healing from war's invisible wounds.]

All soldiers must die in order to live. It's the way the military functions. Fear is a distraction and distractions lead to death. So, as retired signals operator Tim Garthside explains, "You just have to accept that you're already dead. It seems harsh, but if you're worrying about dying, then you're going to die."

The problem is, once you live as if you are already dead, it's hard to change back. And hard to relate to anyone who hasn't crossed that grimly pragmatic divide.

Tim recalls a ride in an SUV headed for Kandahar Airfield. He and fellow soldiers were escorting non-enlisted support staff who were headed back home. Tim saw the panicked look on the face of one. "He looked like a ghost," Tim says. "I remember laughing in my head like, 'What the fuck is your problem? Why are you so fucking scared?'"

Tim shakes his head. "Then I just sort of started thinking about it a bit later. It's like, 'Why am I not scared? What the fuck? Maybe I should be scared.'"

Months later, when Tim himself returned home, he realized that nobody who was there to greet him at the Toronto airport "fucking understood anything about where I'd been. What I'd done."

He isolated himself from everyone he cared about. He moved to British Columbia and gradually stopped speaking to his parents, siblings and friends. "I spent the majority of my time alone," Tim says. "I didn't experience anything except for my own suffering. And I spent a lot of time contemplating why I was still alive. What the point of me being here was. With no real answers."

'This cage on your head'

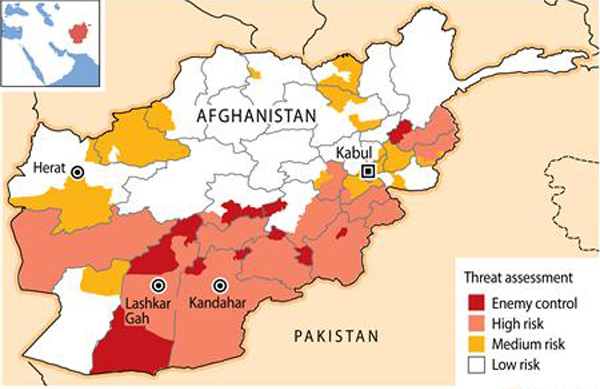

Tim, now 30, was part of the first full Canadian tour in southern Afghanistan. Kandahar is a volatile region. It is the place where the Taliban movement originated. In 2006, when Tim deployed, the area was seeing a resurgence in Taliban activity.

Tim's job description included operating and maintaining communications systems. His location was a small camp in the middle of Kandahar with the Provincial Reconstruction Team. Some days he patrolled with the military police, and he liked that. "I didn't want to be stuck in the headquarters."

In fact, it was at headquarters where "the real traumatic things that really crushed me happened," Tim says. "All my trauma came from sitting in an office chair with headphones on." He was the guy in charge of hearing all the signals going back and forth and letting everyone know what was going on. The headphones were Tim's prison. "It's like you're wearing this trap," he says. "This cage on your head all the time."

Tim was the voice troops relied on if they were in harm's way outside the wire. On Aug. 3, 2006, four Canadian soldiers were killed and 10 wounded when one bomb blew up a convoy and a second targeted the first responders. After the explosions the troops began receiving enemy fire from a nearby compound. Tim was on the line. There was nothing he could do. He couldn't help the injured and those who were dying while they were in the middle of a firefight.

"When you call for a medevac part of the deal is, 'Are they taking fire?' And if they're taking fire then the helicopter is not coming," Tim says. "So I was the one telling them repeatedly that no one's coming. They just kept asking."

Tim has written about that day. In an article published by the B.C. Yukon Command Legion, he wrote, "As their life source poured from their bodies and they slowly and painfully breathed their last breaths, I was the one denying them any hope of survival."

Eight years later, Tim remains agonized from having to repeatedly say, "No one is coming." But while he was there, while he was in it, there was no room for emotions. "When you listen to a radio transmission there's never any emotion," Tim says. "Where does it go? It goes into the guy saying it."

In trying to save his men, Tim spoke with air support, poised to come in and help clear out the enemy. There was no time to waste because once the enemy was gone Tim then could send the medical evacuation so desperately needed. Two attack helicopters were sent up. They were relying on counter-intelligence for information on where and who to target. Counter-intelligence had a source on the ground who could confirm the location of the compound, so through that source Tim was able to tell the pilots where to go and who to kill.

At one point one of pilots saw a man standing on a roof with a rocket-propelled grenade. He asked Tim, "Should we kill him?" Tim's answer was yes -- if the man had an RPG, then yes they should.

So they did. "They cut him in half. Their words not mine," Tim says.

Then counter-intelligence notified Tim they'd lost contact with their source on the ground -- the phone was dead.

It turns out the man on the roof was their source. "I ordered that guy to be killed who was helping us," Tim says. "Who was essentially saving those lives that were standing there needing help. I killed that guy."

At the end of his shift his boss asked if he was okay. His reply, "Of course I am."

'That tipping point'

I'm fine. I'm okay. Those words are like a soldier's mantra. Tim came home barely three weeks after the terrible day of Aug. 3, 2006, and his recurring self-statement was always, "I'm fine." He kept telling himself that since he'd never been shot at or hit by an improvised explosive device (IED), he couldn't be traumatized.

But he was.

He quit the military eight months after returning from Kandahar and ended up in Coquitlam, B.C., where he found work as a crane mechanic. His work became his life. He would get up. Go to work. Come home. Not talk to anyone. Sit alone. Go to bed. Wake up and do it all again. "I wasn't Tim," he says. "I was the job."

But once Tim was past the steep learning curve that becoming a crane mechanic demands, he was left with more time to ruminate. "It progressively just got worse over the seven years," Tim says. "I just turned into this tumultuous ball of emotion. And I was getting really angry all the time and I'm just not an angry person."

Tim had never heard of a trigger before. He thought his panic attacks were because he smoked too much. He thought he was out of breath because the equipment was heavy. The triggers kept getting worse -- he was jumpy, on edge, he wasn't himself -- until one day in September 2012.

"I was just extremely unstable. I could barely keep myself from crying. I just seemed sort of on that tipping point all the time between anger and grief and I was just in pain."

On his coffee break Tim phoned Veterans Affairs. "I just asked for help. I was like, 'Look I've served. I'm a veteran. I served in Afghanistan in 2006. I don't know what to do anymore. I'm at the end of my rope. Nothing I'm doing is working. I'm thinking about killing myself. I don't know what to do. I need help. I don't need help tomorrow. I need help now.'"

The voice on the other end of the line said, "Print out a form and mail it to us then we can help you."

Tim left work, but he didn't own a printer. So he went to the legion and had them print off the form for him. The man printing the form told Tim there was an Afghan veteran there and asked if he'd like to talk to him.

That's how Tim met his friend Aaron, who's a graduate of the Veterans Transition Program at the University of British Columbia. "I didn't have to talk to him about it really. He could just see where I was at," Tim says. Three weeks later he was in the program.

"If it hadn't been for that I probably would have killed myself." Tim stares out the window for a moment. "I would not be here."

'They saw things'

Tim has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Sitting in his apartment, Tim leans over and pets his dog Monty. He looks lost in his memories, lost in his story. It's a story that lives and breathes within him, and one that he's told countless times.

The first time was to Marvin Westwood, a counselling psychologist at the University of British Columbia, and a co-founder of the Veterans Transition Program.

"I'll never forget my interview with Marv," Tim says. "I seriously smoked an entire pack of cigarettes before I went in."

Tim still wasn't sure he belonged. He wasn't sure how he could be traumatized. He felt fearful of opening up. But Westwood "just asked me where I'd served and what I'd done," Tim says. "There was something about him that put me at ease. I felt like I was being understood, and that hadn't happened for me for a really long time."

Westwood says there are wounds not caused by explosions or gunshots. "Some in the military service will let you know that they saw things, and did things they shouldn't have. And the innocence is lost," he says. "The soul injury, the loss of self, they are invisible and yet they are very dominant."

No soldier or veteran is fine, Westwood says. "That's denial. It's part of their military masculine culture. There's a lot of people who do need help and some of them kill themselves, or stay depressed and isolated."

But it doesn't have to be that way. Recovery and restoration is possible. Westwood told Tim he was like an iceberg -- he'd been frozen for a long time and he was just now beginning to thaw.

Lock and key

The Veterans Transition Program is designed for soldiers to help soldiers. "Nobody comes back without wounds. If you go you've been hurt," Tim now sees. "So the basis of that brotherhood is that you've been through hell. And you come out the other side, and you probably have scars -- you do." It was the validation of those scars by fellow soldiers that helped Tim acknowledge his trauma and begin to work through it.

The program is offered over three months. The focus is on storytelling and reenacting those stories to reach a resolution. Westwood says they start by focusing on the positives -- by talking about what they gained and what they learned while overseas.

Then they focus on losses. They call it dropping baggage.

Each person identifies a story or a loss they had during their military experience. They tell the story. They write it out and then they reenact it.

Tim says his therapeutic enactment forced him to go back to the Aug. 3 disaster, and switch back on something that had been turned off that day. "That was really the first time that I'd felt emotion in seven years," Tim says. "A lot of it just involved getting angry and then once I got that anger out of the way there was just grief. A lot of grief."

The metaphor Tim was given was that if you stick your hand in a snow bank it freezes. When you take your hand out the first thing you feel is burning and pain. That's what going back feels like. "Before you can feel any of the good stuff you're going to feel all of the bad stuff," he says. "You are back feeling those same things, and then you can slow it down and deal with the emotions. You do whatever you need to do to release that stuff."

Tim's second enactment was about acknowledging all the pieces of himself he'd lost in Afghanistan. It was about confronting the Tim he was before. The Tim that was drawn to the army before he learned the army would ask him to be already dead in order to stay alive.

During this enactment there was an empty chair across from him. Tim put his soldier self in that chair. And he didn't hold back, "You fucking lied to me," he said. "You told me about the honour and the valour and the truth and all this horse shit, and you didn't tell me about what I'm going to have to fucking carry around for seven years. You didn't tell me any of that stuff. You fucking lied to me."

Tim has done four enactments since starting with the Veterans Transition Program in the fall of 2013. His third enactment brought him back once again to Aug. 3. This time Tim realized he blamed himself for what happened to the man on the roof. All of his self-criticism came rushing back. It was like someone was standing behind him telling him, "You're a monster. You're terrible and you deserve this."

Tim's counsellors asked, "What would you say if it was somebody else standing there? Do you feel bad for him?"

Tim answered, "I'd tell him that it's not his fault, but it is. It is his fault. I'd want him to feel better but... "

Then they asked, "So this person just has to suffer forever because of this?"

Westwood can't offer Tim any kind of memory erasing cure. "You have to remember what you did forever and what you saw," he says to Tim. "But you don't have to suffer from that forever."

Hearing that, Tim says, "just gave me the hope that I can be forgiven even if I can't forgive myself. You can almost hear a lock being turned."

'Who I am now'

What motivates soldiers to share their story? Marvin Westwood believes the want to give back. If they think telling their story can help someone else, they will. And it will help them heal their own wounds. "What they can get back after they drop the baggage, is that they can actually begin to feel hopeful. They begin to imagine that they can have careers. They can have a family. So they can get those things back -- their goals and their aspirations."

With Canada's combat mission in Afghanistan at its close, veterans will increasingly need help transitioning to civilian life. In 2012, the number of suicides in the U.S. military surpassed the number of soldiers killed in combat -- suicides rose to 349, nearly one a day, while combat deaths in Afghanistan numbered 310. In Canada a study released in 2013 says there were 10 military suicides in 2012. But these numbers are deceptive. Only suicides by male regular force personnel are officially recorded -- the statistics don't include suicides by women, veterans who are retired or reservists.

Tim was in the reserves, so if he had killed himself as he says he often contemplated doing, he would not have been counted among those official statistics.

Now Tim is back in school. He's completing an undergraduate degree in psychology at Simon Fraser University. He also works for the Veterans Transition Network, which has expanded to six provinces across Canada and has over 500 graduates. The program, he says, "saved my life."

Tim has been doing everything he can to turn his suffering into something positive. But he expects the trauma will never go away.

"PTSD is a blanket that goes over my brain and it affects everything. It's just reality for me," he says.

In the face of his suffering there is one question Tim gets asked more than others, "Would you do it again?"

His answer is always yes.

When Tim deployed he believed in the mission. He believed that by going he could make a difference. He says he felt ready to do something, change something and be part of something much bigger than himself.

Tim still feels that way. "Things get twisted and turned around and politicized and whatever else, and at the end of the day nothing's perfect," he says. "But we did help people, for whatever small amount of change that may have fostered."

What these soldiers are finding is that there is pain that destroys and pain that transforms. Tim says his scars are a reminder of what it means to be alive. "If I had to go back I wouldn't change a single thing about it because it's made me who I am now," he says. "Regret gets you nowhere."

Tomorrow: On Remembrance Day, the series Soldiers' Tales concludes with a profile of Master Cpl. Byron Crowhurst who was a childhood friend of the writer, and came back from Afghanistan with a diary, and a bracelet, that speak of difficult memories. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: