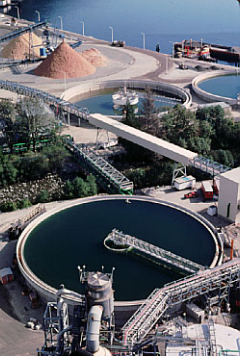

Picture a tanker truck heading away from a pulp mill. It's loaded with a complicated cocktail of toxic wastes, the by-product of mashing trees to produce paper. The sign on the side of the tanker warns of the environmental hazard within and the trucking company has been charged with the responsibility of disposing of it carefully.

Where is the truck going? A hazardous waste facility? A secure landfill? It turns a corner and pulls into another industrial area. The pumps are hooked up and the load is siphoned into the top of a tall silo. Safe and contained, right?

Ah, but what is this?

The trucker heads around his rig and hooks up to the tap at the bottom of the tank, turning it on and filling his truck back up.

Loaded again, the truck pulls out with new cargo, and a new sign stating there is a soil enhancement product within. With a happy toot, the vehicle rolls on down the highway to sell fertilizer to producers in the rich farm lands of a nearby verdant valley.

Far fetched? Maybe not.

Sludge through bureaucracy

It has happened as close as Washington State. In fact, the Seattle Times devoted a special series to investigating the use of industrial waste as fertilizer, which helped spur tougher testing and regulation of the practice.

But now the same thing may soon be happening here, says Delores Broten, senior policy advisor for Reach for Unbleached, a pulp mill watchdog organization based on Cortes Island.

The province of British Columbia is in the process of reviewing policy which could open the doors for toxic industrial waste to be turned into fertilizer and spread on agricultural and other land, with unknown consequences to human and ecosystem health.

The government has given the public 30 days to comment on the impending regulation, but neglected to tell anyone about it, say environmentalists who are scrambling to react before the November 30 deadline.

Ministry of Environment officials sent out an email on November 1 advising several bodies, including the BC Environmental Network, West Coast Environmental Law and others about a public process underway to create and regulate the use of "waste" as soil enhancers. After plowing through seven paragraphs of bureaucratic sludge about regulatory reviews, the reference to a Soil Enhancement Using Waste intention paper can be found.

Idea that won't die

Broten has been working on the issue of pulp mill waste for almost a decade. She got the email, but flagged it as something to go back and read more carefully. Last Thursday, she was alerted to the importance of the message, with less than a week left in the public consultation period. Not only is she shocked at how quiet the ministry has been about their plans, she says the intent of this regulation is the worst she's seen yet.

"The horse keeps breaking out of the barn," she commented wryly.

In 1996, she was part of a government, enviro and industry committee tasked with finding a solution for the mounting problem of waste from pulp mills.

Industry suggested composting and then land-spreading the waste instead of costly landfilling as a solution. Broten and other environmental sector representatives repeatedly demanded industrial wastes undergo testing before being broadcast over the landscape.

"Our position was that we have no problem with this if it is a genuinely beneficial use," says Broten. Draft after draft of a regulation was written, which included limits on certain compounds, testing for around 50 potential contaminants and guidelines on where land-spreading was appropriate.

By 1998, when the Ministry of Environment finally agreed to independent testing to determine the chemical make-up of sludge, the Council of Forest Industries (then-industry umbrella group) withdrew from the committee and the budget for testing was lost.

The issue reared up again in 2000, when Draft Three of the Pulp Mill Sludge Regulation and the Guideline for the Land Application of Pulp and Paper Mill Sludge was introduced.

Broten said the 2000 draft at least demanded testing for more than 50 compounds listed in the Contaminated Sites Act. The new regulation seeks testing for 11.

'Not without controversy'

Not all types of land-spreading need be a concern, but no one knows what the actual environmental impacts of land-spreading sludge are, because for almost 25 years, industry across North America has been denying environmentalists' efforts to get some honest testing done, says Broten.

The proposed regulation seeks to provide a standard to which industry can look if they wish to make use of residuals in a different way, says Graham Kissack, director of the environment at Catalyst Paper (formerly Norske).

He says the regulations are consistent with similar legislation in the United States and elsewhere across Canada. Land-spreading is common in many jurisdictions, he says.

"It's not without controversy," Kissack adds.

Pulp mill companies like Alberta Pacific have done research to determine whether "waste products" can be turned into a valuable addition to local soils. Their website refers to trials done in cooperation with the University of Alberta and the University of Lethbridge, which have demonstrated a significant growth increase in poplar and aspen trees and can yield increases of up to 50 percent in agricultural crops.

Kissack says the proposed regulations will give Catalyst a promising tool for disposing of certain wastes, but at present, the company has their solid waste management situation well in hand. There may be other facilities where this is not the case, he says.

Worries about toxins

Composting and turning waste into a reusable product may sound like a good idea, but Broten warns that much industrial waste contains levels of toxicity that will contaminate the land or the food grown on the land.

She is most familiar with pulp mill waste, but says the components of that sludge are not entirely understood by anyone. Some compounds created by the bacteria in the treatment ponds are unknown to science.

"We do know that it contains a variety of heavy metals, benzenes and phenolics," Broten wrote in 2000 to then NDP Minister of Environment Joan Sawicki. "We also know that other jurisdictions in North America that have experimented with spreading sludge have experienced unexpected problems, and frequently halt the sludge spreading programs in a wave of citizen protest."

Pulp mill sludge is not the only industrial waste to be concerned about. Lest we forget waste from chemical plants, smelters, oil and gas waste and more.

Fly ash, for example, is what comes out of the filters used to catch pollution at the top of industrial smoke stacks. It has been used a lot in many jurisdictions in North America as an additive in cement and as fertilizer on fields.

"You catch it because you don't want it going out into the air and then you spread it on the fields," she says incredulously. In her opinion, it belongs in a secure landfill only.

Fly ash, she reminds us, is the stuff that made workers at the Teck Cominco Plant in Trail sick after they cleaned out the boiler.

"In the proposed regulation, they don't even mention thallium. This is toxic to ruminants at two parts per million and it is found in fly ash," she says.

Public responses

According to Colin Rankin of C. Rankin and Associates, 12 responses have come in through the public process. His firm, which handles many of these types of consultations, typically sees anywhere from 12 to 100 comments depending on how much of a hot button the issue is in the public mind.

"Sounds like this might be one," he says.

The ministry decided not to put out a press release about the public consultation and due to some problems with the website, Rankin says the ministry has agreed to not discard comments that come in after Nov. 30. He is preparing a summary for the middle of December. Ministry of the Environment officials were not available for comment by deadline.

Broten says this isn't good enough. If the public aren't able to get involved now, it will be worse after the code goes through

"The new Code of Practice has no recourse for neighbours of the sludge site, does not require records to be publicly available, and throws the burden on to the medical health officers to object if the application is to agricultural land or within a drinking watershed," she says.

The self-regulating trend

John Werring of the Sierra Legal Defence Fund says this type of amendment process is part of a regulatory trend across the country. The federal and provincial governments are moving toward smart or results-based regulations where standards are streamlined and industry is left to monitor itself.

"From our perspective, the only way to keep industry in line is to have strict regulations," he says. Industry asks to be trusted, but ultimately what all these changes in regulations do is save companies millions of dollars, he says.

Broten, too, finds the finds the process and the proposed regulation lacking, especially from a monitoring perspective. She says the new code seeks to comply with the Organic Matter Recycling Regulation, an existing code of standards for sewage sludge.

"When the Code of Practice is not working for sewage sludge, why expand the same failures to industrial waste like pulp mill sludge?"

Cost savings

Broten says that for some kinds of sludge, composting before spreading might be a way to go. Properly composted waste is a potential soil enhancer for eroded areas and other forestry sites, she says, but that means industry would have to pay more to store the sludge long enough for it to break down.

What firms are pushing for, simple land-spreading, is much cheaper. Selling waste as fertilizer is a far better alternative than paying to haul it away, incinerate or securely store it.

Reach for Unbleached is calling for rigorous and independent testing of pulp mill sludge and prohibiting the land-spreading of pulp mill sludge until these waste materials are known to be safe in the environment.

Heather Ramsay is a contributing editor to The Tyee based in Queen Charlotte City. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: