In 1965, a friend asked Neil Young for a ride. Young was a working musician in Fort William, Ontario and his friend had a show in Sudbury, about 650 kilometers away. On a whim, Neil agreed to drive him there in Mort, his 1948 Buick Roadmaster hearse. Somewhere along the way, the transmission fell out of the car. Neil Young was only nineteen.

Young, who had planned to return to Fort William, took Mort's death as an omen, a sign that he couldn't turn back to either Fort William or Winnipeg, where his mother lived. Heading, instead, to Toronto, his birthplace, he wrote a bunch of gloomy songs about failure and yearning, was dismissed as clichéd in the local paper and skulked around various Yorkville coffeehouses. But even at such an early, feckless age, he would do anything to be a rock star. There were a couple of brushes with success, including an audition in a closet at Elektra Records and a stint with Rick James in the most mind-boggling Motown band-that-never-was, the Mynah Birds. Following on his ambition, he decided that he needed to leave.

In March 1966, after hawking some guitars and ampli?ers that didn't technically belong to him and borrowing a sleeping bag, Young took another hearse across America. This time, with Neil driving the whole trip wired on amphetamines, the hearse carried him to fame. He had set out for Los Angeles, looking for his friend Stephen Stills, whom he'd met in Fort William. During a traffic jam on Sunset Boulevard, Stills spotted a hearse with Ontario license plates and knew it had to be Young. He was only twenty.

From hearse to limousine

Less than a month after landing in L.A., Young and Stills's new band, Buffalo Spring?eld, was opening for the Byrds and entertaining record offers. The hearse was abandoned for a limousine and within a year Young had gone from literally singing for his supper to playing with the Rolling Stones at the Hollywood Bowl.

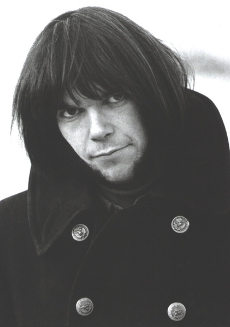

In the decades that followed, Neil Young would become world-famous as the craggy, cavern-browed hippie in the buckskin jacket, his electric guitar chugging along like a steam engine, his acoustic guitar chopping like paddle strokes in a lake.

But for every idea of Neil Young, there is a counter; for every persona or role, a contradiction. He's the Nixon-bashing hippie and the country singer praising Ronald Reagan. The mellow folkie with his acoustic guitar and the dissolute rocker throttling his out-of-tune 1953 Gold Top, Old Black. The rock 'n' roll Luddite who loathes CDs and the dabbler of electronic music of Trans. The patriotic American and the Canadian passport-holder. From these disparate attitudes and guises has come a body of work that is multifaceted, erratic and original.

Wimpy chubbos

This might sound familiar to you. Some bespectacled chubbo walks into a record store. Or some scrawny spaz breaks into his older brother's room. Or some slob sneaks into a party. (Any one of these scenarios can work.)

This guy's life, up to that point, has been a series of unremitting indignities. He can't get his hair right. He can't get with women. His jokes aren't laughed at. He spends his weekends watching videos with his grandmother, who makes him stop movies whenever she hears a curse. He's too tall. He's too short. (Details may vary.)

This is where the album or tape or CD comes in. The music he's heard up until then is too crass, too wimpy, too calculating. It might do for other people and he has to remind himself that not everyone listens to music the way he does. Not everyone is looking for consolation.

But today he plays this record and it leaves him with his hair standing on end, like in a science-fair disaster. It makes him feel cool; it feels like secret information. He realizes not only that he's a fan of this rock star, but that he's always been his fan. Even before he heard of him, he was a fan. He was a fan from the womb; he just didn't know it at the time.

'Neil Young saved my life'

Maybe this was you. It certainly was me; it certainly is me. Neil Young saved my life.

I was thirteen or fourteen, and the video for "This Note's for You" had just come out. Neil Young was about to emerge, like a Granola Rock phoenix, from the shithole of critical derision and commercial irrelevance. Although music television has never been a haven for normal-looking people, at least in those days people over the age of twenty-two could still occasionally appear onscreen. I knew there had been a stink around the "This Note's for You" video, something to do with Michael Jackson with his hair on fire. Mtv had banned the video, which somehow led to it being played endlessly on Canadian television.

"This Note's for You" was followed closely by "Rockin' in the Free World," one of those songs that have since been so overplayed that no one bothers listening to it. A song that assails complacent consumerism and hypocrisy; it has become an anthem for sanctimonious, meathead rage among those who take at face value its mocking anti-slogan of a title. The song gets played at Hard Rock Cafes; boomer politicians belt it out, in shirts and ties, at political fundraisers. Again, there was a memorable video, its humor was more subtle, more self-mocking than that of the video for "This Note's for You." Young played a homeless tv-wielding seer, then a glam rocker with lipstick and hairspray. I was extremely impressed. I found the song on the album Freedom and wore down my cassette copy listening to it again and again.

'Ragged Glory'

So I bought his next album, Ragged Glory. I had become a fan as Young was experiencing a critical renaissance. He shared a stage with Sonic Youth and recorded with Pearl Jam. His songs were covered by the Pixies and Dinosaur Jr. At that age, I wasn't quite cool enough not to enjoy Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix, just as I liked punk and indie rock.

I was taking guitar lessons and I formed a band. The bassist (who is still a musician) brought a copy of "Cinnamon Girl" into my parents' basement. This was my first acquaintance with Young's earlier music, and I loved the opening guitar riff and clapping, the one-note guitar solo, the joyful howls, the minor key-sinister fuzz-guitar lick near the end. Over the next few years, in a number of bands, many hours would be spent noodling through Crazy Horse standards like "Cortez the Killer," "Like a Hurricane," and "Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)." All of these songs were easy to play-and easy to play very loud.

Sometime after my thousandth basement rendition of "Hey Hey, My My," I lost my mind. I started buying Young's older albums: Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, then Harvest and After the Gold Rush, then Tonight's the Night and Zuma. I read Neil and Me by Neil's father, Scott Young and John Einarson's Don't Be Denied, the essential book on Neil's Winnipeg years. (Young's semi-authorized biography, Shakey, by Jimmy McDonough, would appear in 2002. Another major biography, Zero to Sixty, by Johnny Rogan, was published in the U.K.) I joined the Neil Young Appreciation Society, and my very first publication was a song-by-song review for the nyas fanzine, Broken Arrow, when I was eighteen. In it, I likened Neil's guitar face to that of someone who's been kicked in the groin.

Fan psychology

Why was I such a fan? Let me count the reasons. There was that voice, so unusual -- many would say so screechy or alley-cat-that you knew he wasn't skating by on gloss. I remember watching television as a child and seeing a man in a flannel shirt and sunglasses singing on the 1985 all-star famine-relief song "Tears Are Not Enough," Canadian music's answer to "We Are the World." He looked like a lumberjack-pirate among the zipper-clad and poodle-headed Canadian talent, which included Corey Hart, Geddy Lee from Rush and Paul Shaffer. There was something even stranger about his voice. How did he ever become famous? When the song's producer, David Foster, told him that his singing was flat, Neil replied, with characteristic assurance, "That's my style, man!" And yet it would take me a few more years to realize that this man wasn't Gordon Lightfoot.

Young, whose idyllic childhood was ruptured by a near-fatal polio attack and his parents' divorce, sang like the child who is the father of the man, in the voice of innocence singed by experience. His lyrics balanced stoner abstraction ("Is it hard to make arrangements with yourself / When you're old enough to repay but young enough to sell?" in "Tell Me Why") with compelling, fragmented imagery ("Big birds flying across the sky" in "Helpless"). Young's trippy songwriting style-which bowled over distinctions between you and me, you and her, now and then, before and after, here and there-was unified by his melancholic vision, his tenuous tenor, his unerring sense of melody.

It was the peculiar, sometimes begrudging way he confessed feelings that made them inevitable, rather than simply a formal requirement of rock songwriting. And yet the off-the-cuff manner in which Young produced his music-songs quickly written while he was laid flat by illness or injury, then recorded with a minimum of rehearsal and studio gimmickry-revealed not only a desire for rawness and immediacy but a fear of equivocation, a fear of his own fear to commit. Even when Young was ambivalent, he wavered fiercely and noisily.

Exaulting melancholy

Without idealizing it, he exalted melancholy, which, novelist Thomas Pynchon once mused, "is a far richer and more complex ailment than simple depression. There is a generous amplitude of possibility, chances for productive behavior, even what may be identified as a sense of humor."

Then there was his guitar: the way it shrieked and whinnied sounded outside of music, less about melody or hot licks, and more about punishment, more like a stream of anguish.

By the time I finished high school, Young had become something of a role model for me. Looking back, I could have done worse. Young was the embodiment, in his appearance, his singing, his music, of a type of anti-beauty. To an awkward kid, this was appealing. Young sought beauty in frayed edges and worn-out patches. He reveled in bum notes, in buzzing guitar strings. Even his album covers had a rough, unfinished quality. The solarized photo of Young on the cover of After the Gold Rush would cost a Fotomat operator his job. Jim Mazzeo's far-out line drawings for Zuma of a naked woman, a "danger bird," and some pyramids look at first to be found art from a discarded Denny's placemat.

Neil Young pilgrimage

In August 2004, I decided to follow the same route Young took from Winnipeg to Fort William (now Thunder Bay), and then from Toronto to Los Angeles. With three pot-smoking buddies and a hatbox's worth of space cakes, I crossed North America in one triangular swoop, traveling 14,000 kilometers and 7,500 miles, through five provinces and fourteen states, in twenty-two days. I visited places that were important to Neil and a few people associated (albeit tangentially) with Neil, and stopped in Auburn, Washington, to see Young play at Farm Aid 2004. It was a trip: in the here-to-there dictionary sense, in the foggy mind-journeying granola sense, in the pratfall sense.

My Wild Neil Chase was cooked up on the fly and with little premeditation. I had just turned twenty-nine and, like a lot of people approaching thirty, felt as if each birthday was a door being slammed loudly and angrily. Even my twenty-eighth birthday had been a stinging rebuke. For me, it meant I could no longer be a dead rock star who had died at twenty-seven. My chance to choke-gloriously-on my own vomit had come and passed. Now I was a year away from thirty, life's first big speed bump.

Most of my friends were grown-ups. I didn't count myself among them. Grown-ups were those with spouses, mortgages and car payments, and produce in their refrigerator. Not someone like me, a novelist who stole toilet paper from his parents. People I knew were not so much trying to have children as they were not not trying to have them. They'd reached a certain age and succumbed to the inevitable gravity of reproduction. Not me. My mother had so much grandchild-envy that she'd recently encouraged me to find a special anyone to knock up.

Septuagenarian party animal?

This is not to say I was some adolescent party-animal, getting loaded on shots of Jägermeister. If anything, I had the lifestyle and income of a septuagenarian pensioner. I played in monthly poker games with my married friends, drank beer at the Legion Hall on Thursday nights and took my dog to the beach.

And this is not to say that I was discontent in my unattached, semi-squalid developmental limbo. The novelist Mordecai Richler once remarked to the effect that no one grows up dreaming of catering the Great American Bar Mitzvah. I've taken his point to mean that some part of a writer, however small, refuses to accept reality. There remained a patina of danger about being a novelist. At least it went over great at parties.

Only a few years earlier, I'd felt ahead of the game. Without ever having had a steady income, I had gone directly from life as an underfunded graduate student to being a working writer. I had published my first novel when I was twenty-five. The book came out and was a very modest non-failure. I would look myself up on Google and find out that a university student in Georgia thought my book sucked compared to The Nanny Diaries. Hey, who was I to disagree? I'd bump into someone who'd given me a bad review at a party and fantasize for weeks about taking one of this reviewer's books, smearing it with dog shit and mailing it to his doorstep. I was now officially a writer. I'd become the person I wanted to be.

Neil Young medicine

Things started going wrong with my second novel. The first thing I noticed was how unbearably hard it had become to write. I was no longer working in a vacuum and my ambitions had grown larger. It took much longer than my first, years longer. I spent much of 2003 covered in hives; I'd wake up with welts along my arms, my legs, sometimes an eyelid. A blood test showed no food or fabric allergies. I was allergic to my novel.

But I persisted, and after three years cobbling away, I had a manuscript that pleased me. And yet it didn't please those big-hearted people who turn piles of manuscript pages into books and give writers money and author tours. It would seem that I'd turned out something like the prose equivalent of anchovies. This wasn't what I'd expected. I decided to put my novel "in the refrigerator." I stopped writing fiction and tried not to think about it. I needed a break. I needed Neil Young, or at least his music, to save me again.

This is strange but true: everything I know about being young I learned from Neil Young, a jowly man approximately twice my age and now hurtling toward senior citizenship. "Well, I keep gettin' younger," he sings in "Crime in the City," "My life's been funny that way." He bristles against expectations; he chooses spontaneity over precision, passion over perfection. This was exactly what I wanted in my life, in my art. What Young called reckless abandon. The expressions go kid at heart or old soul, but these are mere consolations for most people. For Young, old is a choice, a train you can elect not to board. Being young is an awareness of possibility, an unwillingness to stick with what one already knows and lead with one's strengths. And, in my opinion, this frame of mind is much harder to achieve than the physical agelessness exemplified by news readers or yoga instructors.

One can be a rock star at sixty, just as there are teenagers who are already planning to sell life insurance. As a novelist turning thirty, working through the night, searching for the right word to describe a one-note guitar solo, then sleeping into the afternoon, I felt like someone looking for a place in between.

From the book Neil Young Nation, © 2005, by Kevin Chong, published by Greystone Books. Reprinted by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. Click here to purchase the book. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: