In Robert Thurman's book, Infinite Life: Awakening to the Bliss Within, he describes an incident that happened when he was a young monk, just beginning his Buddhist studies (in New Jersey of all places). On his way to buy milk for tea one day, Thurman writes, "I experienced a disorienting sensation that I can only describe as the feeling of push-pressure on my tailbone suddenly dislodging itself. The pressure gone, I immediately saw that I had always been feeling as if I were being pushed along from behind toward my destination...The change in sensation gave me a pronounced feeling of relief, a sense of release."

Something similar could happen to you while watching Louis Malle's documentary Phantom India (L'Inde fantôme). The documentary screens as part of a major Malle retrospective at the Pacific Cinematheque in Vancouver, "The Fire Within: Louis Malle The French (and Indian) Films," beginning January 13 and running through to January 30th. Originally made for French TV, Phantom India is made up of seven episodes with a total running time of 378 minutes. The Cinematheque is screening all seven of the films in one single day (Sunday January 29th). If you thought Peter Jackson's King Kong was long, you ain't seen nothing yet. Pack a lunch.

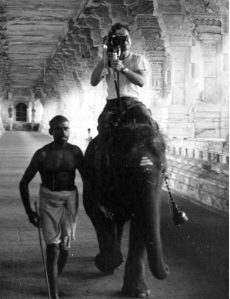

The retrospective was initiated by the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York, and in their program notes, the genesis of the documentary is explained. In 1967, Malle was hired by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to make a series of films about India. The original project was supposed to last eight weeks, but stretched into months. After his initial experience, Malle raised the money to return to India and keep filming. Along with cinematographer Etienne Becker and soundman Jean-Claude Laureux, the director traveled the length of the country, trying to capture a series of moments.

'The impossible camera'

The process was, in his words, "No plans, no script, no lighting equipment, no distribution commitments of any kind...It was enormously important for me, and I'm still trying to make sense of it today." Given that Louis Malle has been dead for over a decade, it behooves you, gentle viewer, to try to do the same in his absence.

Keep in mind the word, "retrospective," because that's exactly what you will experience. But at the same time, many of the ideas that Malle was exploring about the subjective nature of art are relevant right now.

The first episode, entitled The Impossible Camera, sets out the methodology. Malle states that his intent is not to impose a narrative but merely to let images and events occur. Whatever the camera captures, on a moment-to-moment basis, is what the film will become. The process isn't unlike dragging a net along the bottom of the ocean floor; what it pulls up -- a startling array of life, in shades of radiant pink, vermillion and dusty brown -- will then be combed through, reassembled and constructed into something else. It is here where the director keeps encountering a vexatious problem: the inability to escape himself. (Which is what Robert Thurman and indeed, much other Buddhist thought, is also about.)

For Malle, for whom film HAD previously been an escape, this becomes a terrible struggle. Watching fishermen pulling in their catch, he is catapulted back into his own memory of a French beach 15 years earlier. Even on a distant beach, he can never be entirely in the moment. It is a Marcel Proust-like dilemma: always forsaking the real for the imagined, the actual for the image.

Crowded paradise

But the brutal economic realities of India also disrupt this process. The idyllic scene on the beach dissolves into an extended haggle over the price of the fish. Malle often simply turns his camera on and lets it run, recording images and events initially without commentary. In the narration itself, added later, when Malle states his own distance from the images filmed, his perspective has shifted and moved on somewhere else.

The realities of India both confound and bewitch Malle (nowhere on Earth seems quite as photogenic) but the reality behind the images is so complex that the scenes captured give lie to reality. What looks like a tropical paradise -- a place of limpid pools and deep green jungle -- is overpopulated, desperately poor and riddled with colonial leftovers. The camera is both a means and a burden in this place. As the director states, it "marks them as doubly foreign": white westerners, with their technology. Filming a pair of women gleaning bits of grain in a field, he feels like a thief, stealing something ineffable from these nameless, faceless figures. He is right to feel this way, but is a voyeur who is aware of what he's doing any better than one who isn't?

The camera's inability to differentiate between surfaces, or offer any deeper depiction of reality is the central concern of the film. The camera, after all, merely records; it is a great unseeing eye. It is the function of the director, as narrator and guide, to situate the images in the film within a larger context. But Malle doesn't trust himself; he is as much a creature of his time and place as the people he is filming. Moments of connection are few and far between. He wants purity, a level of the real that is not folklore or tourism, but of course, he is as bound to his own cultural notions as he is to his skin.

This idea is made startlingly clear when he interviews two young Parisians who are also traveling in India. Initially, they are full of admiration for a country that they think is somehow more pure than their own, more in touch with the land and the elemental pull of life at its most basic. Interviewed a few weeks later, everything has changed; one of the young men, previously so impassioned and fervent, is now sick and emaciated and just wants to go to home to his parents.

'Every ornery fibre'

Watching the documentary in 2006 is a strange experience and current audiences may find many of Malle's political ideas quaintly anachronistic. It was, after all, 1969, a time that seems almost as distant now as rural India was then to Malle's modernist French sensibilities.

You can't help but view the film with this in mind, but still, the film has an immediacy, a life, that can only be captured in such discursive, sprawling length, where moments emerge and then melt back into the larger fabric. This quality is shared by another far different text. Film critic David Denby, writing about James Agee's enormous tome, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, in the New Yorker, covers similar turf.

A young man sets out to visit a foreign place, although in Agee's case, he was visiting the rural American south, which was (and perhaps still is) a foreign country. He comes back with words and pictures (Walker Evans' photographs) and a sense of being somehow changed by his experiences. Denby describes Agee's approach to his subjects: "In an age largely concerned with the 'masses,' Agee was impressed by the notion of other human beings idiosyncratically are what they are, in every ornery fibre." A visitor from another place, there to document the lives of people, different than himself but was he really a "recording angel," as Denby describes him, or merely another angle recorded?

'Giving reality its due'

Like Agee, Malle is also obsessed with the inability to really know the "other." But in Malle's documentary, despite differences in culture and language, the image of film enables us to see and perceive, that behind the blank subjectivity of the camera, there is another eye, and behind that, the mind and subjectivity of the filmmaker.

"Giving reality its due," was one of Agee's obsessions, and it is also the driving force of Malle's film, although the actual realness of things confounds him; the sheer scale of difference becomes overwhelming. He watches a man push a sewing machine down a lonely highway, and states, "If I had seen this in France, it would have seemed surreal." But in India, he merely watches. Over and over, he runs into his own set of cultural preconceptions. Upon seeing a pack of hungry vultures snake their bald and bloody heads into the empty eye sockets of a dead cow, his impulse is to immediately cast the characters, and to make the scene into a tragedy about life, and the inevitability of death and decay. But to his Indian guide, the scene means nothing so grandiose. It merely an everyday occurrence, nothing to get excited about.

Time is another Malle-ian obsession, whether the filmmaker is fighting it, taming it, or capturing it. Throughout the film, Malle makes statements like, "Time has stopped," or "Time has disappeared," or "Time has ceased to exist." He wants off time's ceaseless forward march, and occasionally, he gets it, if only for a moment. A period of days in which the filmmaker and crew film at an Indian dance academy is one such instance. The school, founded by famous atheist-suffragette-theosophist Annie Besant, teaches different forms of Indian dance.

Besant herself, no stranger to adventure, wrote, "Never forget that life can only be nobly inspired and rightly lived if you take it bravely and gallantly, as a splendid adventure in which you are setting out into an unknown country, to meet many a joy, to find many a comrade, to win and lose many a battle." Here the infinite and the ordinary meet and share the same heated air. Dance: immediate, physical and utterly transitory is described by Malle as a bridge between "the present moment and eternity." He and his crew film the dancers, until they are finally kicked out for being too disruptive a presence.

The organism of film

But the director is more than someone who watches, he is also a participant in the process, especially during a local festival where pilgrims pull an enormous towering wagon, full of priests, and colourful effigies through the streets. "I forgot who I was," says the filmmaker, and this experience, of being part of an enormous singing, dancing, sweating human organism, comes close to the infinite bliss that Robert Thurman talks about. The physical moments, whether in dance, religious rites, or the repeated gestures of work or worship have the capacity to take us into a state unself-consciousness, into a place, and time, of grace. The impossibility of staying there, in the present, is paradoxical within the medium of film, since film is itself, a time based medium, or as Malle describes it, "Time's tamer. Time's slave." But somehow, he pulls it off and, if only for a moment, in this film, you are truly there. The fact that this vision of India, along with the director who made it, no longer exists, doesn't matter. It is much more than a figment, or a leftover. It is timeless.

The idea that movies can or should be experiential may be undergoing a resurgence. The Italian film, The Best of Youth, a very full 358 minutes, has made many critics' lists. Satantango, director Bela Tarr's 1994 film, that runs 420 minutes, is currently screening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, but there are plans to bring the film to DVD, where you can watch from the safety and comfort of your own bed, which can also come with its own set of problems. Watching Phantom India from my own bed, I found myself more than once, being lulled gently to sleep by Louis Malle's calm voice.

This is the time of year that major studios let the dogs out, hence the presence of things like Grandma's Boy or The Ringer. No better examples probably exist of what Susan Sontag called film's state of "ignominious, irreversible decline." But if you'd like to ponder the infinite universe instead of watching Johnny Knoxville behave even more mentally challenged than usual, then Louis Malle to the rescue. You too can be in the moment, even if that moment lasts six hours.

Dorothy Woodend reviews films for The Tyee every Friday. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: