Inside Griffin Art Projects’ North Vancouver gallery space, a study in convergence is underway. Intersecting Orbits is, in many ways, an illustration of how commonality and difference can happily coincide in artmaking.

Orbits is a new exhibition of posthumous work by the late Joan Balzar and Michael Morris, two West Coast artists born a generation apart whose creative outpouring explores the confluence of art and science, a quality that Balzar referred to in her work as “something of the power of the cosmos and the power of paint.”

Co-curated by Lisa Baldissera and David MacWilliam, the show explores the two artists’ commonalities and divergences in the form of conceptual art, abstraction and experimentation, as well as the continuing impact and legacy of their work.

Both Balzar and Morris called Vancouver Island home. In addition to their West Coast roots, both studied at the Vancouver School of Art (now Emily Carr University of Art + Design) with many of the same teachers.

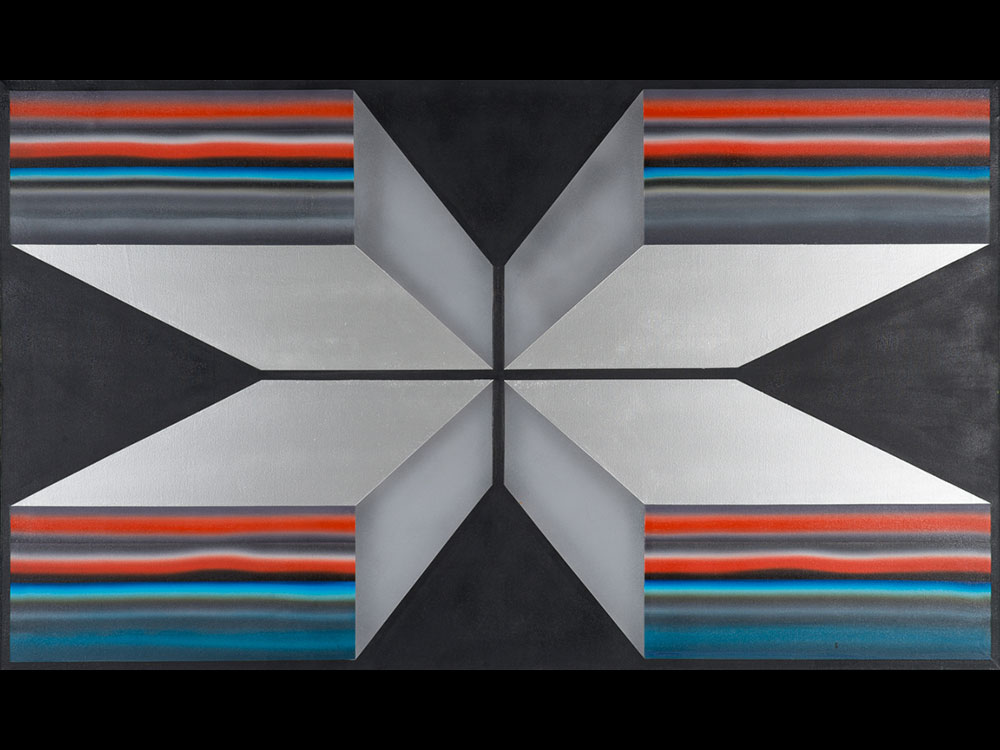

Born in 1928, Balzar grew up in Victoria but lived large portions of her creative life in Mexico and Guatemala. Unlike a great many painters from her region, landscape held little interest for Balzar — instead, the jetpack atomic era of hard-edged technology fascinated her. This is well in evidence in her work, with its clean precise lines, neon tubing, Plexiglas and silver metallic colour.

Working in the relatively new-for-its-time medium of acrylic paint, the care and exactitude necessary to create the gradient colour and hard edges in Balzar’s paintings required an almost superhuman level of attention to detail. The works are large, meticulously planned and constructed, so that they almost appear to be machine-made.

But if you look carefully, there are indications of the artist’s hand at work: tiny pinpricks of paint on an otherwise pristine colour field. Whether these were purposeful or not is hard to say, but for an artist with such a ferocious dedication to precision, it’s hard not to think that they’re there for a reason. So, too, is the line that occasionally wobbles — perhaps an indication of human fragility in a machine age. Or is it something to do with our fallible, imperfect humanity sneaking in sideways? These intentional interjections give the painting a vulnerable kind of poignancy.

On the other side of Balzar’s hard-edged clarity is Michael Morris’s work. Born 14 years after Balzar in 1942, Morris moved with his mother, Rita, to Vancouver Island in 1946 at age four, eventually settling in Brentwood Bay. Mother and son shared a mutual passion for artmaking. In the photographs that introduce the show, they’re captured painting together.

This relationship was a pivotal part of Morris becoming an artist. His impact on the cultural community is extraordinary. In addition to co-founding Image Bank and Western Front, Morris was a curator for the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Best known for his large-scale abstract paintings, Morris worked in media ranging from photography to performance art to printmaking. But as a young gay man growing up in a relatively staid part of Canada, Morris’s sexuality came out in oblique ways in his work. After periods of study in Vancouver and the Slade School of Fine Art in London, England, Morris moved to Berlin to participate in a period of residency supported by the German Foreign Artists Program.

A large painting, purported to be of the Berlin Zoo, a spot for gay cruising in the 1980s, is a particularly striking piece of work from this period. The painting Within a Dark Wood (1985) was created during a time when AIDS was decimating a generation of gay men. In an interview with the Victoria Times Colonist, Morris recalled the terror of the AIDS crisis.

“It hit Berlin like a tsunami, the art scene particularly.... It was a dark time.” With this context, the green foliage depicted in the work starts to seem less like tropical lushness and more akin to tangled darkness.

The pure pleasure of so many different ideas, expressions and investigations is in abundance in this exhibition. Some serious, some silly and some austere — it’s a pleasure to luxuriate in all of it.

In 1998, Morris returned to Brentwood Bay to care for his mother. After her death in 2005, he inherited her art collection. The collected works from Morris and his mother make up a good chunk of Intersecting Orbits, running the gamut from Andy Warhol’s silkscreened cow to ceramics from prominent West Coast potters like Wayne Ngan, Glenn Lewis and Michael Henry.

Some of the most charming work in the collection is a pair of watercolours from painter Maxwell Bates, an early mentor of Morris. In one image, an elderly woman, believed to be Rita Morris, poses saucily for the artist, hand on hip in a strange gargoyle mask, while another woman at the edge of the frame is seemingly lost in a fit of giggles.

It is so immediate, odd and ridiculously funny that I wanted to know more about the artist. Another of Bates’ watercolours depicts Michael Morris's first commercial exhibition at the Douglas Gallery in 1967 in Vancouver. The accumulated crowd is so preoccupied in drinking and gossiping that they barely seem to register much else. The art hanging behind the crowd’s head merits not a glance, but the gaiety and conversation appear to be free-flowing and riotous.

In writing about a given piece of work, one is tempted to say, “Just go and look at it,” and then we can talk. But do words sometimes get in the way of art’s pure enjoyment, clouding the visual experience?

On a Sunday afternoon in the Griffin, a sizable crowd gathered for a walk through the show with the two co-curators. It was fascinating stuff, but the experience can feel akin to falling down the rabbit hole: one thing leads to another, and before long one is knees-deep in the history of the Western Front or reading about the early days of the Vancouver art scene.

The sheer amount of written material to take in can sometimes feel a bit overwhelming, and in some ways, it takes you down a different path from the art itself. Do you really need to know the history, exhibition record, awards and influences that a given artist has accrued to appreciate and enjoy their work? Not really. Certainly, words can deepen the experience of the visual, knowing when and why and how something was created, and whose work informed whose.

But at the very heart of it is an ineffable mystery: there was nothing and then there was something. It’s the making that is the most important. In the case of Morris and Balzar, the depth of their respective impact is clear in the work itself, as well as the connections that spring up in the collected work of other artists who had an impact on them.

There is a certain lingering mournfulness in Intersecting Orbits, perhaps because both artists have passed on. The show also speaks to a burgeoning moment in the cultural communities of Victoria and Vancouver, when things like conceptualism still felt brand new and a wee bit wild. The sheer pleasure of the art itself, in all its manifestations, is so great that it doesn’t really matter if you don’t know all the details about its creation. It still speaks.

‘Intersecting Orbits: Michael Morris and Joan Balzar’ runs at Griffin Art Projects in North Vancouver to May 5. ![]()

Read more: Art, Gender + Sexuality, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: