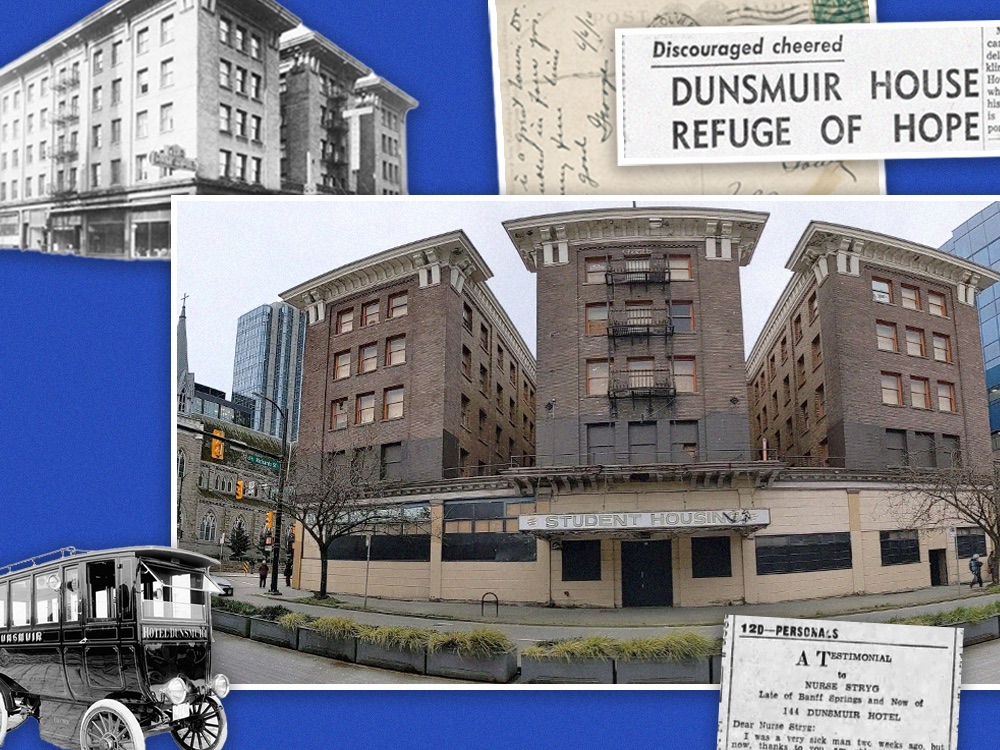

The imposing brick building at Dunsmuir and Richards has been many things: a hotel, a muster point for merchant seamen, housing for returning veterans, a refuge for low-income men, a gathering place for the thrifty and the down-and-out, a student hostel and a homeless shelter.

But for the past decade, this prominent Vancouver heritage building at 500 Dunsmuir St. has sat vacant as its current owner and the city go back and forth over how the block can be redeveloped.

“For this project, we are hopeful for a mixed-use development that will revitalize downtown Vancouver,” Holborn Group of Cos. told The Tyee in an email. “However, we are unable to provide specific information at this time as we are still undergoing studies to determine the right mix for the project.”

The developer is well known in Vancouver for completing the controversial Trump tower, a moniker that earned the ire of local politicians when it opened in 2017. Today, the building, which is located at 1161 W. Georgia St., no longer carries the Trump name.

Holborn is also known as the owner of the Little Mountain site, where over 200 units of social housing were torn down in 2009. Today — 15 years after the provincially owned land was sold to Holborn — the six-hectare site is still mostly empty, and the social housing units have not yet been fully replaced.

Like Little Mountain, Dunsmuir House is a large, prominent piece of land that was previously owned by the government and has a long history of being used to house poor people. In both cases, Holborn has shared grand plans to redevelop the property into a new neighbourhood — only to let the land sit empty for years.

The Dunsmuir Hotel was an important hub in Vancouver’s commercial growth in the first four decades of the 20th century. Later, as Dunsmuir House, it became a key part of the city’s social safety net for over 50 years.

Let’s take a closer look.

‘A grand place’

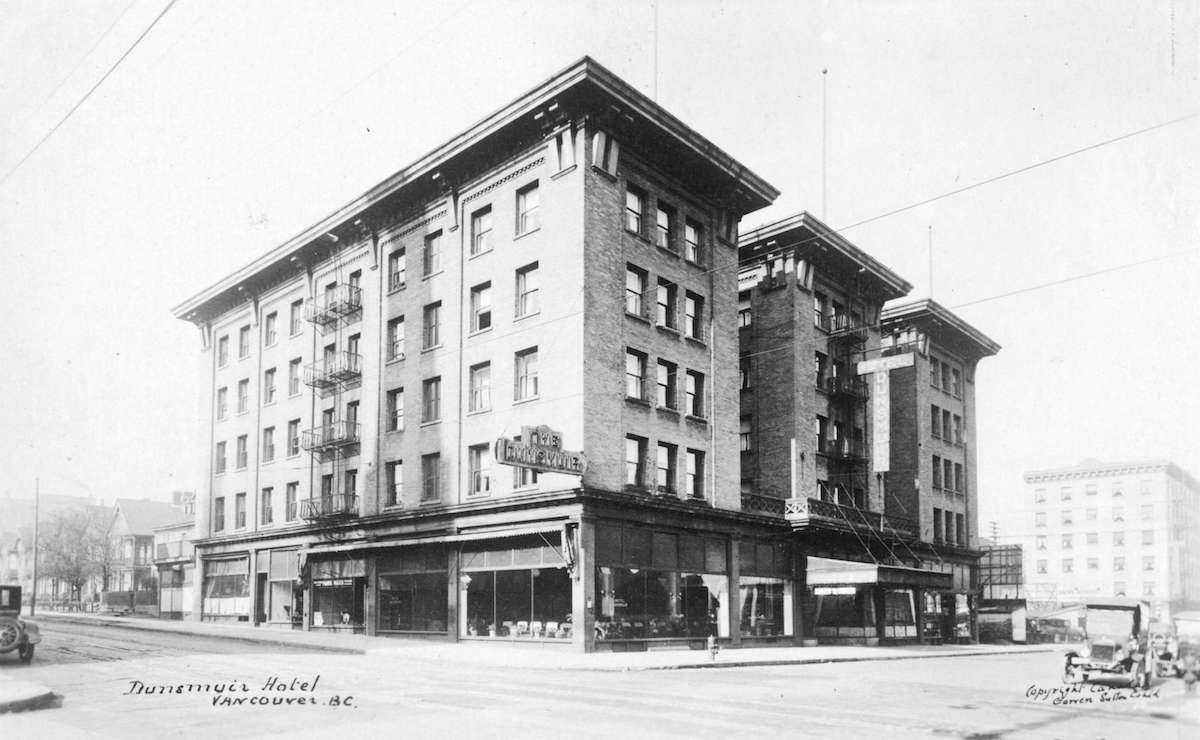

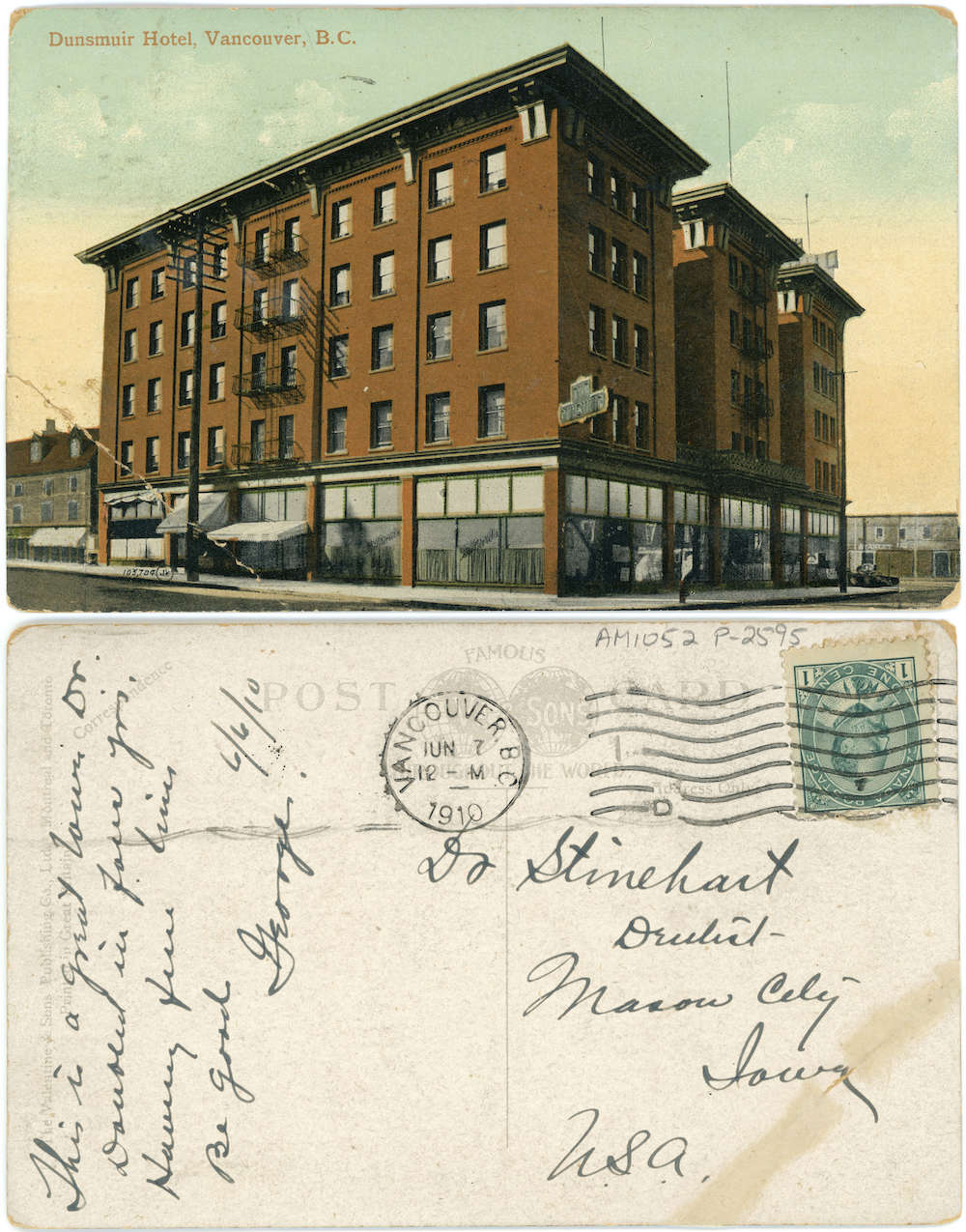

When the Dunsmuir was first built in 1907 it was the second-largest hotel in the city, rivalled only by the original Hotel Vancouver a few blocks away at Georgia and Granville streets, according to civic historian John Atkin.

According to Atkin’s research, the 168-room hotel was built on land owned by the Dunsmuir family, Victorian-era industrialists who owned the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and coal mines near Nanaimo as well as other businesses. The Dunsmuirs also built Craigdarroch Castle, an opulent home in Victoria that is now a popular tourist attraction.

Looking through newspapers of the day, it’s clear the Dunsmuir Hotel served many purposes, Atkin says. Gatherings were regularly held in the opulent dining room, and some of the hotel rooms were used as offices for real estate or other businesses.

“It held all the big celebrations,” Atkin said. “And it was noted for its interior: it had a large rotunda, a huge lobby, and the dining room was always called out as something quite special. So it was a grand place when it was built.”

Atkin is also intrigued by a 1930s-era newspaper advertisement featuring a testimonial from H. Rasmusen, who said he was a “very sick man” who was helped by a woman called “Nurse Stryg” at the Dunsmuir Hotel. “Massage is a wonderful thing,” Rasmusen wrote, “and I would like people to know it helped me.”

The war years

By 1942, the building had been purchased by the Canadian government and was being used as a “manning pool” for the merchant mariners who were responsible for running perilous shipping journeys across the Atlantic and Pacific to keep Britain and its wartime allies supplied with fuel, ammunition and other vital goods.

“It was accommodation largely for British captains and seamen,” Atkin said. “They would come out to Vancouver and then they would wait for merchant ships as part of the war effort.”

It was a similar story for the Hotel Vancouver, which was also used by the Canadian military during the war years.

When the war ended, Vancouver faced a housing crisis as soldiers returned, often with young families in tow, to find that housing was scarce and expensive. Veterans occupied the Hotel Vancouver to protest the lack of housing, and their efforts led to the building being operated as a hostel for returning soldiers for two years, according to a 2016 story by Vancouver Sun reporter John Mackie.

By 1949, the government had sold the Dunsmuir Hotel to the Salvation Army. The hotel now entered a long period of providing housing to low-income people.

A small room, a simple life

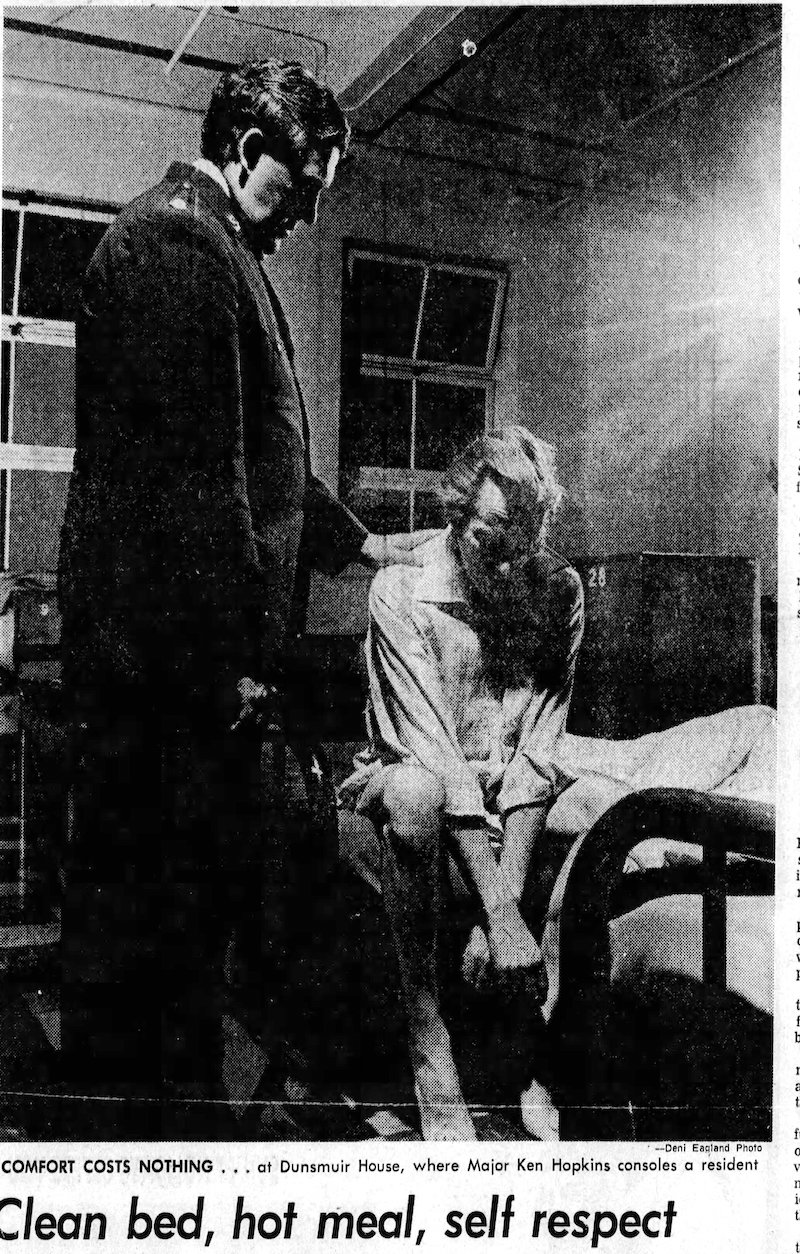

With its fancy dining room converted to a cafeteria, Dunsmuir House provided a gathering space for single, low-income men, many of whom lived permanently in the 168-room hotel, where drugs and alcohol were forbidden.

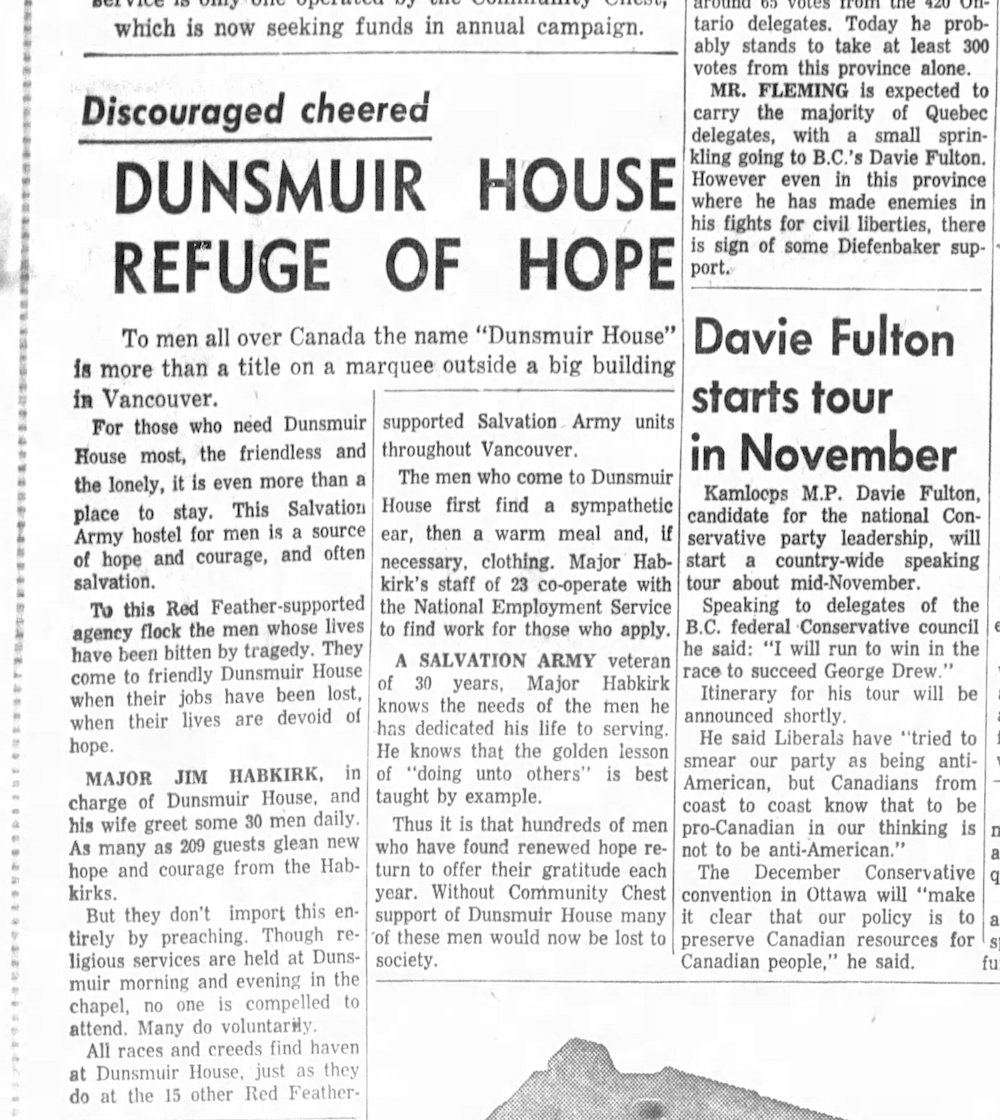

In a 1956 Province article, the building was described as a “refuge of hope” for “men whose lives have been bitten by tragedy. They come to friendly Dunsmuir House when their jobs have been lost, when their lives are devoid of hope.” Religious services, regular meals and assistance getting back into the workforce were some of the services provided by the 25 Salvation Army staff who ran the building. In the 1950s, many of the residents were new immigrants, according to the recollections of a longtime bookkeeper in a 1975 Province article.

It was also a handy place for a reporter to find a colourful “down-and-out” character for a story about urban life.

“For the last 22 years of his life ‘Johnny Boy’ — as he likes to be called — has been engrossed in the study of man’s life to the universe. An involved topic for a gent of 93, but one on which he can speak for hours to anyone who would listen,” a story from the Nov. 22, 1976, edition of the Vancouver Sun begins, for example.

By the 1970s, Dunsmuir House was providing cheap housing for students on the top floor and a 30-bed dormitory, in addition to 168 rooms mostly occupied by single men.

In the 1970s, Atkin says, he and his fellow art students would often head to the Dunsmuir’s cafeteria for a meal. The building still retained traces of its former glory; Atkin remembers taking photographs of the beautiful tiled floor. “It was the best cheap lunch going and you had that interesting social interaction, which you don’t get as much today,” he said.

In 1981, a brief mention of Dunsmuir House appears in a Province story about Christmastime charity — a story that starts by mentioning that welfare payments have been cut that year, so poor families are expected to have a hard time. Another Province story in 1982 describes an increase in young homeless people who have come west looking for work during the economic recession.

Through the decades, Dunsmuir House also came in handy to provide emergency and temporary housing. For years it acted as a halfway house for prisoners released on parole. In 1965, when guests of another downtown hotel were displaced by a fire, they found refuge in the lounge of Dunsmuir House. In 1993, the Vancouver Sun reported that Dunsmuir House provided shelter for 36 Chinese migrants found in “a dilapidated boat” off the coast of B.C. Thirty beds were also earmarked for homeless people, according to a Jan. 7, 1993, story in the Vancouver Sun.

Throughout the temporary uses, Dunsmuir House continued to permanently house older single men. In 1990, Vancouver Sun journalist Bob Stall called the building “the upscale end of Skid Row” and recorded the prices of rooms and beds: $260 a month for a room, $8 a night for a dormitory bed.

“Nobody is turned away for lack of money,” Stall wrote. “You can always get a free ‘welfare bed,’ even after government offices are closed. They’ll do the paperwork tomorrow.”

A final story about this era of 500 Dunsmuir: In 1997, a lawyer from West Vancouver took up permanent residence at the old hotel. Dugald Christie had lived a comfortable middle-class life, but he had been a longtime member of the Salvation Army and had spent his career representing marginalized people.

According to a 2006 obituary in the Business Examiner, Christie resigned from the Law Society of British Columbia and moved to the Dunsmuir when he became “disillusioned” after losing “a case that involved a brain-damaged dock worker.”

“He had a small room and lived very simply with few possessions,” Christie’s colleague John Pavey told the newspaper.

Buying and selling 500 Dunsmuir

By 2001, the Salvation Army had plans to sell the aging Dunsmuir House and build a new building called Belkin House at 555 Homer St. The Salvation Army leased the building back from private landlords Geoff and Tanya Hughes for several years after it made its $4.5-million sale, until all its residents had been relocated, according to news articles from the early 2000s. The Dunsmuir House’s 50-year run of providing permanent housing to low-income people ended in 2003. According to court documents filed in 2021, the property had by that time “fallen into extensive disrepair.”

According to a 2004 Vancouver Sun article, the Hugheses then owned two other single-room occupancy hotels: the Hotel Canada at 518 Richards and the St. Helen’s at 1161 Granville St. Both of those buildings are now owned by the province and operated as supportive housing.

For a few years, the Dunsmuir was operated as a student hostel, mostly housing English-language learners from outside of Canada, according to a 2006 city council report. Then, in 2006, Holborn bought the property.

In 2006, developer Simon Lim proposed redeveloping a parcel of land that included Dunsmuir House. City staff were prepared to offer Lim extra density for a mixed residential and commercial development, in return for restoring Dunsmuir House and including more commercial space in the finished redevelopment than originally proposed.

But that redevelopment never proceeded, and in 2009 Dunsmuir House was still sitting empty as the 2010 Olympics approached. The city had another problem: Mayor Gregor Robertson had campaigned on a promise to end street homelessness, but downtown residents had been bitterly complaining about two new homeless shelters. Those shelters, at 1442 Howe St. and 1435 Granville St., closed in the summer of 2009, leaving many of the young people who had lived in them homeless, according to articles in the Vancouver Courier.

With money from the city and BC Housing, Dunsmuir House was leased from Holborn and fixed up anew to again provide housing for the city’s down-and-out, opening in the fall of 2009. Dunsmuir House was operated as a homeless shelter by two non-profit housing providers. Atira Property Management provided day-to-day operations, while RainCity offered a range of social services.

According to 2021 court documents, “over the course of the BC Housing lease, the building became increasingly deteriorated and many of the rooms were left uninhabited.” The building was finally closed for good in 2013.

In 2016, Holborn’s CEO, Joo Kim Tiah, gave an interview to the Province about his redevelopment plans for the Little Mountain site and the Dunsmuir block. He said he was working on rezoning both properties and hoped to break ground in 2018 for a mixed-use development on the Dunsmuir Street site that would “include retail, office, hotel and residential units.”

Holborn currently owns most of the block bounded by Dunsmuir, Richards, West Georgia and Seymour, with the exception of 570 Dunsmuir St. and 555 W. Georgia St.

In 2018, the city attempted to charge Holborn the empty homes tax for 500 Dunsmuir, but the developer successfully fought the tax in court after the city twice rejected the company’s attempt to appeal the $144,740 fee.

In court filings, Holborn claimed that in 2009 the city changed the zoning of the downtown area that includes Dunsmuir House to allow only commercial developments, not residential. Therefore, the company argued, “any use of the property for residential became impermissible.”

The city had previously argued that the zoning still permits the existing building, Dunsmuir House, to be occupied. But Holborn claimed that under the city’s own rules, that use was no longer permitted after Dunsmuir House became a vacant building in 2013.

Court filings show the city agreed to set aside the empty homes tax.

‘People did speculate on poor people's homes’

Over the past two decades, advocates like Wendy Pedersen, who keeps a close watch on the city’s stock of single-room occupancy hotels, have tried to raise the alarm about the disappearance of this kind of housing.

These century-old hotels, which dot Vancouver’s downtown and Downtown Eastside neighbourhoods, feature small rooms with shared bathrooms. Often called the housing of last resort, SROs provide housing to many of the city’s poorest and most marginalized people.

As these buildings have been bought and sold, rooms have been renovated to rent for much higher than people on welfare can afford, and tenants have been evicted.

While many SRO buildings have been bought by the city or province, Pedersen believes more needs to be done. She estimates that 500 to 800 SRO rooms are currently sitting empty in Vancouver, and she thinks the city could be much more aggressive in using its powers of expropriation.

The city has used those powers only twice, in 2017 and then again in 2018, to expropriate the two most notorious SROs in the city, the Balmoral and the Regent.

“All of the closed SROs should be expropriated like they did the Regent and the Balmoral, and they should be added to the list of future redevelopment for social housing,” Pedersen said. “Because those were people's homes, and people did speculate on poor people's homes.”

Atkin warns that the longer a building is left empty, the more vulnerable it is to damage. If the redevelopment of the block ever actually happens, Atkin believes Dunsmuir House should be earmarked for some form of affordable housing.

“Given its previous history, the internal arrangements of that building could really work well with the housing and the social services combined,” he said.

Holborn insists it is still moving ahead with the redevelopment plans. “We submitted a Letter of Enquiry on December 20, 2019, followed by a Policy Enquiry Process submission on November 10, 2022, to the City of Vancouver,” the developer told The Tyee in an email.

“Unfortunately, both those submissions were not supported by the City’s staff. However, we are engaged with city staff once again and with City Council’s goals to expedite development approvals, we are optimistic about the potential rezoning of the site in the near term.”

City staff say they cannot comment on developer inquiries because they contain confidential information. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Municipal Politics, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: