In North America, we are facing a looming agricultural crisis. Or, rather, an intersecting series of them. Soil degradation, antimicrobial resistance due to industrialized farming practices, drought and a fossil fuel crunch are just a few of the brick walls we find ourselves heading towards at full speed.

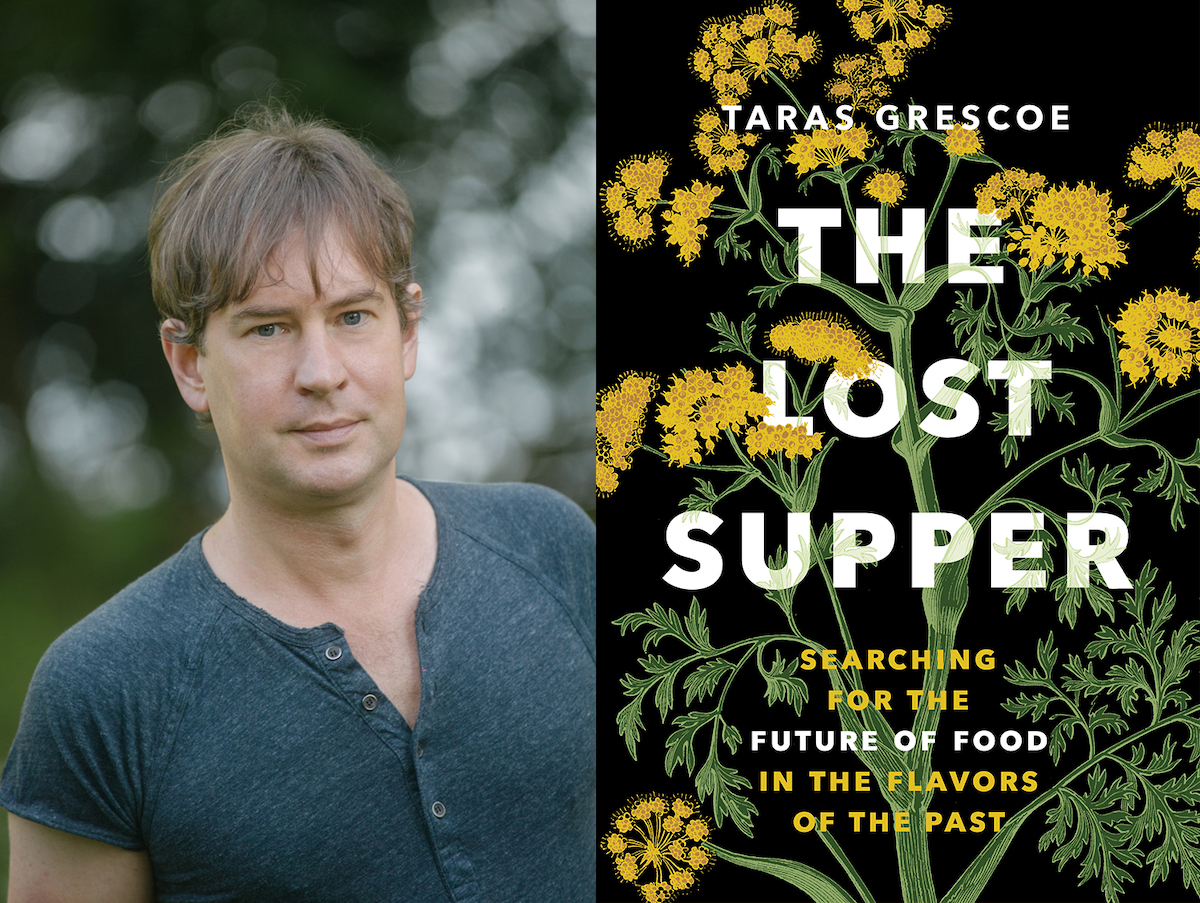

Enter Taras Grescoe’s The Lost Supper: Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past, published by Greystone Books in partnership with the David Suzuki Institute. Grescoe has previously written books about public transit and eating small, readily available fish.

In The Lost Supper, he makes the case that rather than turning to technological innovation to save us — that’s what got us into this mess in the first place — we should be looking to the past for a better understanding of how to eat well while mitigating catastrophe.

We caught up with him to talk about cheese, long-lost plants and botulism. We also dished about environmental writer George Monbiot. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: One thing you have in common with innovation-focused agricultural writers (and investors) is a belief that conventional western agriculture isn’t working, and needs — rapidly — to become more sustainable. But rather than looking towards vertical farming or indoor aquaculture or lab-grown meat, you advocate for looking to our collective pasts to find a way forward. Why is your way the best way?

Taras Grescoe: There has been a long trajectory towards the industrialization of food, and the techno futures that are being advocated right now are leading us to even more industrialization — blander food, less flavour, more consolidation, more corporate control. I don’t think that’s the place we want to be heading.

For example, people like George Monbiot, the Guardian journalist who does a lot of great analysis of the industrialization of food and the environmental impact of our current farming practices, ends up advocating for an even more industrial future when he advocates for things like lab-grown protein.

I’m of the opinion that we should be going in a different direction: that we should be looking to sustainable foodways, traditional ecological knowledge and the wisdom of the past. I think that the industrialization of food is leading us to a very bleak place. And people kind of do the math and say, "There’s eight billion people on the planet now; how do we support 10 billion people?" The environment is not going to support our current food system.

They’re correct when they say that. But I don’t think the answer is the technocratic solutions that are proposed by some environmentalists and, in general, the global food industry. The current industrial food system just seems to be heading to a place of less and less diversity, more and more scientific intervention, and I think that there is traditional knowledge that can guide us towards the future.

By picking and looking at a variety of foods from around the world, from a variety of epochs, I’ve tried to show that there’s a lot of hope that can come out of these ancient ways, these historic and prehistoric ways.

You write in the book that your diet really doesn’t include much meat. So I was wondering if you could talk a bit about why you gravitated towards writing about animal products like insects, fish sauce and cheese and pork in the book?

I’m not really a vegetarian. In fact, I’m not a vegetarian at all. I eat seafood. I wrote a book about fish and seafood called Bottomfeeder arguing that it’s the last wild food on the planet. And making the point that the human appetite is having a huge impact on the oceans, the rivers and lakes, and that we need to change our way of eating. I eat eggs and dairy. Occasionally, I eat ethically raised meat. It’s a very occasional treat. I believe hospitality is really important, so if I’m offered something in goodwill, I will consume meat products.

The problem is that we are consuming too much protein as individuals. In the developed world, in Europe and North America, we’re getting twice the grams of protein we need per day. In the developing economies, especially in China and India, protein consumption is increasing. It’s really unsustainable. They say that we’re going to have to increase the amount of protein we’re producing by 50 per cent by mid-century, which will have an incredible impact on the planet and on our ecosystems.

So I make the case in the book that we should be eating less protein, and we should be willing to value it more. We should be asking questions about where it comes from, and doing our best to seek out sustainably raised, ethically raised protein, whether it’s eggs, dairy or actual meat.

I’m aware that it’s hard to make this case, because it’s hard to say that we should be eating more expensive food. But it’s a question of spending the same amount of money but eating these proteins less often, which is actually better for your health.

I also believe that foods like Wensleydale farmhouse cheese, if they’re produced in a sustainable way — if the livestock are raised properly — it can actually enrich the soil. To say that we should take livestock completely off the land ignores the fact that well-grazed animals can actually help the soil, which is the ultimate source of all the food we eat. I’m thinking of things like the idea of bringing back the Buffalo Commons, of, you know, pasture-fed beef. Not in the Amazon. We shouldn’t be cutting anything down to graze beef. But in places that are already grasslands, it’s actually a good way of bringing fertility back to the soil and increasing biodiversity.

I’m arguing for a return to the diversity of the past. And the diversity of the past, in terms of the plants, the animals that we ate, actually contributes to our own health and it contributes to the health of our planet.

I wanted to ask you about cheese! In your chapter on Yorkshire Dales hard cheese, you suggest something that sounds very appealing to me personally — basically, that we should all be eating more cheese. Why is farmstead cheese in particular — which is made using milk collected from the farm where the cheese is produced — a “very concrete step toward healing our broken agricultural system”?

The farmers I met in the Yorkshire Dales, the Hattons, have their own herd of critically endangered Northern Dairy Shorthorn cows. They’re maintaining a breed that was on the brink of extinction. So by buying and seeking out that particular cheese, you’re supporting a breed of cattle that was on the brink of disappearing.

One of the big problems we’re facing is a severe lack of agro-biodiversity. Most dairy cows around the world, especially in Europe and North America, are Holstein Friesians. Most of them come from just two bulls. There’s a huge lack of diversity in their DNA. And that’s a real risk for food security. So right off the bat, by seeking out and buying this more expensive — I’m the first to say it — cheese from these cheese farmers, you’re adding to the stock of biodiversity in the world, which is very important.

The other thing is that these particular cows, the way that they turn up the meadows, the way that they graze, actually increases local biodiversity. It increases the range of plants, the grasses, the flowers. Their manure supports local species. And I have to say the fields that I saw there were very rich in life. Otherwise they would have been quite marginal, quite bleak. They had been grazed to death by sheep.

The Wensleydale most people are familiar with is the kind of chalky stuff that you get at Christmas and eat with cranberries and Eccles cake. This is a very different cheese made with raw milk. It’s a beautiful hard cheese and the taste of it captures the entire farming system. With every bite, you’re tasting the meadows, you’re tasting the flowers. It’s a living cheese that changes from week to week and month to month.

I’ve heard that it’s hard to find these cheeses. That’s one of the criticisms that could be levelled at this book, that I’ve picked out a bunch of esoteric foods from around the world. And what relevance does that have for people?

So I have to point out that there are equivalents in Canada. I live in Quebec. It’s easy for me to get Pied-de-Vent cheeses here. They’re wonderful, soft cheeses that are made with a breed of cow that was brought over with Jacques Cartier in the 1530s. I have been to the place where it’s produced, but I can get it in cheese shops near to me in Montreal.

You can find equivalent products all around you, in most parts of North America. But you have to seek them out. You have to reconnect with agriculture, which you can often do in your cities just by asking around, by finding the places that sell them. But by making those consumer choices, you are doing a lot of good for the world. You’re supporting small farmers, you’re supporting soil fertility, if we’re talking about animal products. And you’re boosting agro-biodiversity, which is really important for the future of humanity.

Everything that pushes us in the direction of industrialization, of lab-raised foods, I find is sort of 20th-century thinking. “Technology will improve everything”: there are limits to that. The wisdom is in the soil, and the soil is becoming depleted. It’s becoming contaminated. It’s becoming less and less fertile. By seeking out something like a Stonebeck Wensleydale cheese, in a strange way, you’re bringing hope and fertility back to a world that is becoming more and more impoverished.

I did want to ask you about food safety. Is that something you were thinking about as you were writing this book — like when we hearken back to old foodways, melding the wisdom of those times with what we now know about food safety and bacteria? One of the things I’ve seen, as someone who’s also very interested in food and food security, is people talking about drinking raw milk, and water-bath canning things they absolutely should not be water-bath canning. How do we meet the past and the present in that way? What should people who are interested in this food be doing? Are there regulations, or guidelines that the government should be changing, to allow smaller-scale production while ensuring we don’t accidentally get poisoned with botulism or salmonella or E. coli?

Well, that’s something that is not really within the purview of this book. I mean, those are big questions. I have given some thought to them. Let me say this. I think that one of the best things that I’ve done, and an interesting thing other people can do, is to try to deindustrialize their own kitchen, their own diet. Something that I had a lot of time to do during the pandemic. And I suppose it’s risky.

I made my own garum out of Portuguese sardines. I have to admit, the first taste of it was — well, we had poison control on speed dial just in case, but turned out to be okay.

But a lot of the other things I do are really very safe. Lactobacillus fermentation is really very safe. There are thousands of years of experimentation behind making sourdough bread, behind making kefir, behind making yogurt, behind making your own cheese, behind making your own kimchi. If you follow the instructions, you’re gonna be OK.

I’m not advocating experimentation for everyone. But the advantages of doing things like that are that you have more autonomy. Because you’ve stepped away from industrial food, you realize that not everything has to be mediated by going to the supermarket or by some kind of commercial interaction, and you reconnect with older foodways, and you find out who is providing the food in your area.

Wendell Berry said that eating is an agricultural act, but also that we’ve all become industrial eaters. I don’t want to be so much of an industrial eater. I don’t want to just be opening packages and putting things on plates and heating them in the microwave. These industrial food systems actually produce a lot of health problems, food scares, contamination. Because, you know, when food is shipped out, and the contamination happens, all of a sudden it’s all across the country. If my kimchi is bubbling and has gone off, I know right away, because I know exactly how it’s supposed to smell and taste.

In your chapter on silphion, a once-popular food and medicinal plant thought to be extinct, it seems like the same thing that may have unearthed this long-lost plant is also what could make it disappear once again — human appetite. How do we balance our taste for the past with our tendency to love things to death?

Silphion is sort of the holy grail of food history. It’s something I really wanted to tackle. And the opportunity came up when a Turkish scientist, Mahmut Miski, claimed that he’d found it. I really wanted to follow up on that. This one was close to my heart. But when I got to Turkey, it turned out that the presumed silphion plant, Ferula drudeana, was still in a perilous state. There are only possibly 600 plants left in Turkey, 300 of them in a botanical garden and 300 in the wild.

So I’d gone all that way, National Geographic sent me there, and I was, you know, torn. And Miski was very much torn too, because there’s a lot of interest from pharmaceutical companies and this plant could have a lot of medicinal properties. He’s worried that there could be a kind of gold rush, and it’s going to disappear.

As best we could we obscure the location of the plant. Believe me, I’m not advocating that high-end gourmets from around the world try to consume this. We had an experiment in a botanical garden in Istanbul where Sally Grainger, an expert in ancient Roman cookery, came out, and we used a few stalks of the Ferula drudeana and its resin to cook things. It was pretty convincing. It fits the description perfectly, as best we can tell from the images we have on 2,000-year-old coins from North Africa.

The disappearance of this plant was the first recorded example, in written history, of the disappearance of a species, any species, driven by human appetite. And, of course, that’s the risk of writing about it. Will I contribute to its extinction? That was part of the tension of that chapter and part of the tension of the experience.

That’s not the case for many of the breeds and cultivars in the book. In most of these cases, seeking these things out will allow them to thrive, in the way that, say, wheat as a species has thrived because of our tendency to consume it, to make it into bread.

Silphion was the toughest one to include in the book. I’m glad I did, because it’s such an important mystery in food history. But it was a dilemma.

The basic message of this book, though, is that diversity is resiliency, and by adding diversity to your diet, you’re contributing to the resilience of natural ecosystems. ![]()

Read more: Books, Food, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: