The names of the roads, laneways and plazas in south False Creek harken back to the area’s industrial past. Greenchain, Sawcut, Millyard, Sawyer, Moberly, Bucketwheel and Millbank, to name a few, reference the sawmills, railway or surveyors that preceded this mixed commercial-residential neighbourhood.

But Leg-in-Boot Square? The namesake for that one, as a reporter for the Province quipped in 1977, is “a mite ‘controversial.’”

A search of local newspapers for mention of the square, designed to be a shopping and dining centre for the 1970s development, reveals a bit of confusion around the inciting incident, mainly whether it happened in 1886 or ’87. Majority consensus says that in July 1886, just a month after the great fire that destroyed much of Vancouver, a knee-high boot was found on the then-marshy shores of south False Creek. In that boot was a human leg from the knee down, complete with foot. But the rest of the body was missing.

The then brand-new Vancouver Police Department allegedly mounted the boot and its accompanying appendage on a pole outside their headquarters. Thanks to the fire, the police department was operating out of a tent at the foot of Carrall Street at the time.

And there the leg-in-a-boot stayed for two weeks, waiting for a one-legged person to claim it. But nobody ever did, and the boot and its leg were lost to time.

In 2013, the Vancouver Sun’s “This Day in History” column dug up a July 29, 1886, clipping claiming the leg and boot were found by a man named Wood in a small stream off the creek.

The foot and leg were in “an advanced stage of decomposition,” the Sun notes, adding the police chief at the time estimated the leg had become detached from its owner two or three months prior.

While many sources claim the mystery was never solved, the Sun article says local historian John Atkin cited a long lost book, The Queen’s Highway, claimed a body missing its lower leg had in fact later been discovered in the nearby woods.

The account of the boot being put on display by the police seems a bit “far-fetched,” Atkin told The Tyee, adding the story did not appear in either the British Colonist paper in Victoria or the British Columbian paper in New Westminster, both considered papers of record at the time.

The Vancouver News was “the equivalent of the community newspaper for that day,” he said. “Again, in the language of the period, it’s probably exaggerated a bit.”

The Queen’s Highway, on the other hand, reported that more of the body had been discovered than just the leg, Atkin said, and also implied that it was “possibly a bear or cougar that had taken the fellow.” It was likely the man had been camping on the shoreline at the time of his demise, Atkin added.

Vancouver, incorporated as a city in 1886, was an “incredibly small, very crude settlement,” Atkin said. At the time, it ran from Waterfront, to west of where Carrall Street is and up to where Hastings Street is today.

With very little housing available, informal settlements outside the official city limits were not uncommon. “Sometimes they might have put some money down and got a chunk of property, and they would set up tents and camp,” said Atkin.

But if it was Crown land, like False Creek had been declared — despite the area’s importance as a key settlement and harvesting site for Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) and Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) — squatting on land for three years, making improvements to the plot and paying the title fee made the property yours.

Not the last foot in a shoe on our shores

Vancouver had a population of around 1,000 people in 1886, with a higher population of trees than buildings or people.

Leg-in-Boot Square’s entry in Namely Vancouver: a Hidden History of Vancouver Place Names by Tom Snyders and Jennifer O’Rourke, notes the macabre discovery of the leg in the boot was not unusual: two other rotting corpses had been found in the area around the same time.

It’s not so unusual today, either. But no one is publicly displaying any of the floating feet-in-shoes that have washed up on our shores more recently.

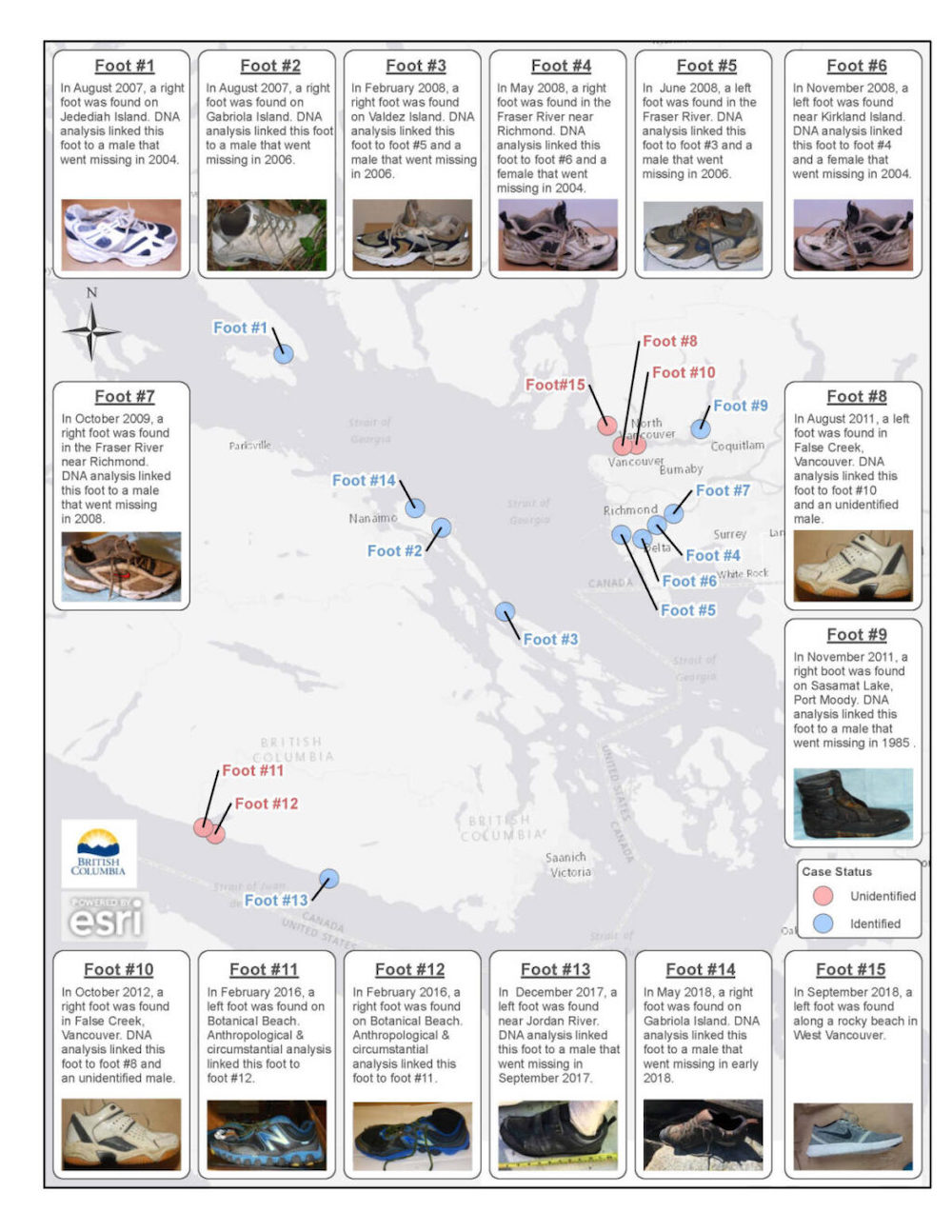

Maclean's reported in 2008 that at least 45 disembodied feet in shoes have come ashore in the Salish Sea since 1990.

It’s a phenomenon that happens on shorelines worldwide. But because of both Leg-in-Boot Square’s namesake and the spate of 14 unattached feet in shoes that came ashore in British Columbia and Washington state between 2007 and 2012, even American media have referenced Vancouver and its leg in a boot when trying to make sense of their own grisly beach discoveries.

Another six feet in shoes have floated to the surface since then, the most recent one discovered just outside Victoria earlier this year.

As the Maclean’s article notes, so many feet floating up in such a short period was alarming. Especially for a province already agog over the recent murder trial of Robert Pickton, a serial killer who preyed on sex workers and other women made vulnerable in the city’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood.

But the explanation turned out to be less scary: since shoes, especially sneakers, float, these feet were likely once attached to people who died at sea, becoming detached from their bodies naturally via decay or being eaten by other sea creatures. Thanks to sea currents, the people whose feet landed on B.C.'s shores likely met their ends well before and possibly away from the eventual sites of discovery.

Making a home in the leg in a boot

By the late 1950s, what would become Leg-in-Boot Square was home to a dwindling number of sawmills, creosote and asphalt plants, and shipbuilding businesses.

“False Creek was really biologically dead. It was just a mess and polluted beyond belief,” Atkin said.

But much of the south side of False Creek was still Crown land and therefore out of the municipality’s jurisdiction.

Fortune smiled upon Vancouver city council, however, when the provincial government showed interest in expanding Simon Fraser University on top of Burnaby Mountain, on land that then-belonged to the City of Vancouver.

“The inducement to give it up was that the city was given all of the Crown water leases along the south shore of False Creek,” said Atkin.

The land exchange took place in 1968. A few years earlier, in July 1960, the BC Forest Products sawmill on False Creek South had burned down, taking approximately four city blocks of the industrial neighbourhood with it.

The fire and the land exchange “set in motion then this whole re-examination of False Creek, the south shore. Ultimately there was a council committee struck that started looking at things, and then there was some UBC planning-types brought in,” Atkin said.

“That’s where this idea of the transformation to housing takes seed.”

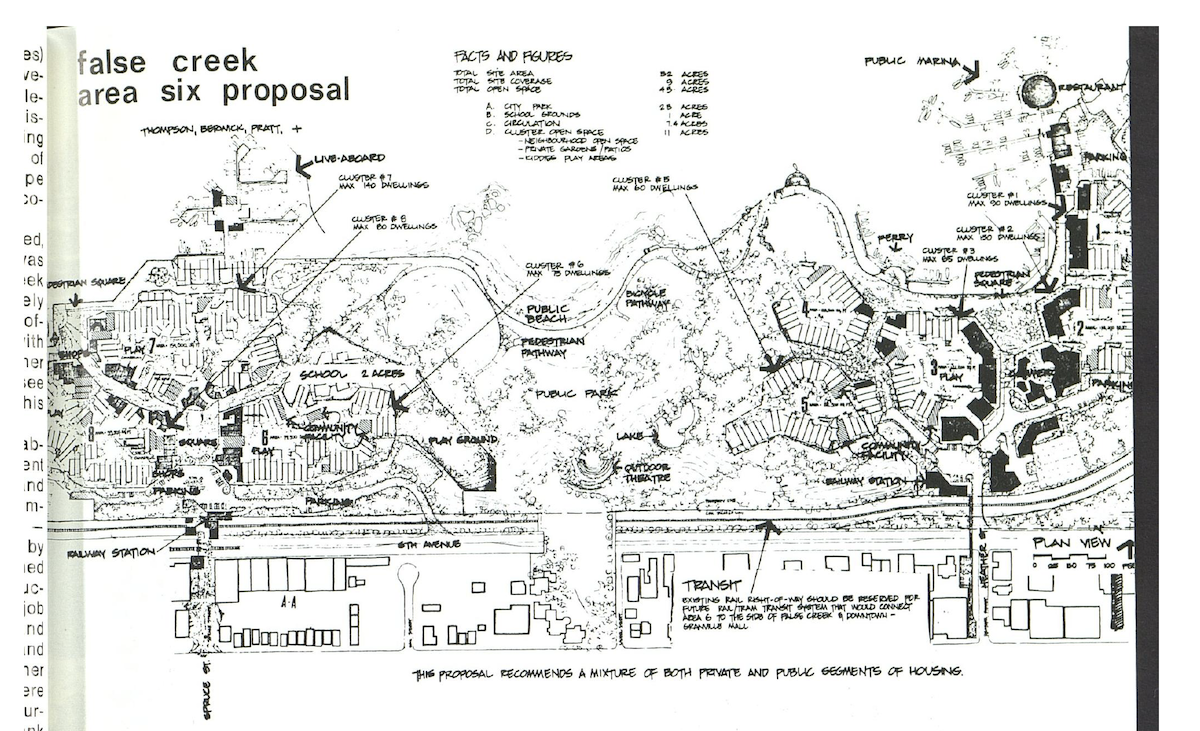

Leg-in-Boot Square and its mixed residential and commercial buildings were part of the first phase of redevelopment of 400 acres of south False Creek from 1972 to 1975, headed by then-TEAMS party members mayor Art Phillips and councillor Walter Hardwick.

Phillips wanted to see people living, as well as working, in and around downtown Vancouver, Atkin noted, which is why the city went for a mix of residential and commercial spaces on False Creek, a kind of proto-Vancouverism.

Hardwick, who was an urban planning student in the late 1950s when he dove into False Creek’s land economics as part of his master's thesis, would go on to chair the steering committee for the redevelopment of False Creek South, including Granville Island, and turn the once industrial waterfront into a mixed-income, almost car-free neighbourhood.

In addition to having commercial spaces on the main floors of the buildings in the square, a June 1980 article in Canadian Architect noted leg-in-boot also stands apart from other buildings on the creek for having solid concrete exteriors rather than stucco. The square’s paving stone courtyard features lines that point to various natural and built scenic vistas, complete with a fountain porthole to peer at them through.

It is unclear why the city’s planning department chose to name the square after the mysterious leg in a boot, says Atkin, noting there was no official naming committee for False Creek’s roads.

“To their credit, they decided to take a look at what was there on site and tried to do site-specific naming,” Atkin said. “And I suspect somebody came across the leg-in-boot story and thought it was funny enough.”

Phillips himself went on to buy a townhouse in Leg-in-Boot Square with his wife, former journalist and then-future finance minister Carole Taylor. The Vancouver Sun credited this move for boosting the neighbourhood’s popularity.

In 2021, the City of Vancouver rejected a staff proposal that would have seen a tripling of density in the neighbourhood, which is currently home to just under 6,000 people, by adding more market rental and strata units. The city’s co-op housing in the area would also have been demolished and relocated from their current waterfront locations to Sixth Avenue.

While Phillips passed away 10 years ago this year, there is still opportunity to live in his old stomping grounds.

For just $2.5 million you can own a three-bedroom condo at 666 Leg-in-Boot Square. Yes, really: the square that houses less than a half dozen buildings somehow managed to claim the Mark of the Beast for one of its addresses.

But at $917 per square foot, the scariest part of this story remains the asking price. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: