- Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism

- Cambridge University Press (2023)

"Marxist” has become an all-purpose pejorative. Antisemites, alt-right conspiracy theorists and their ilk among right-wing culture warriors disparage social justice advocates as Cultural Marxists. And now federal Conservative party leader Pierre Poilievre is describing both Pierre Elliott Trudeau and his son Justin as plain unmodified Marxists.

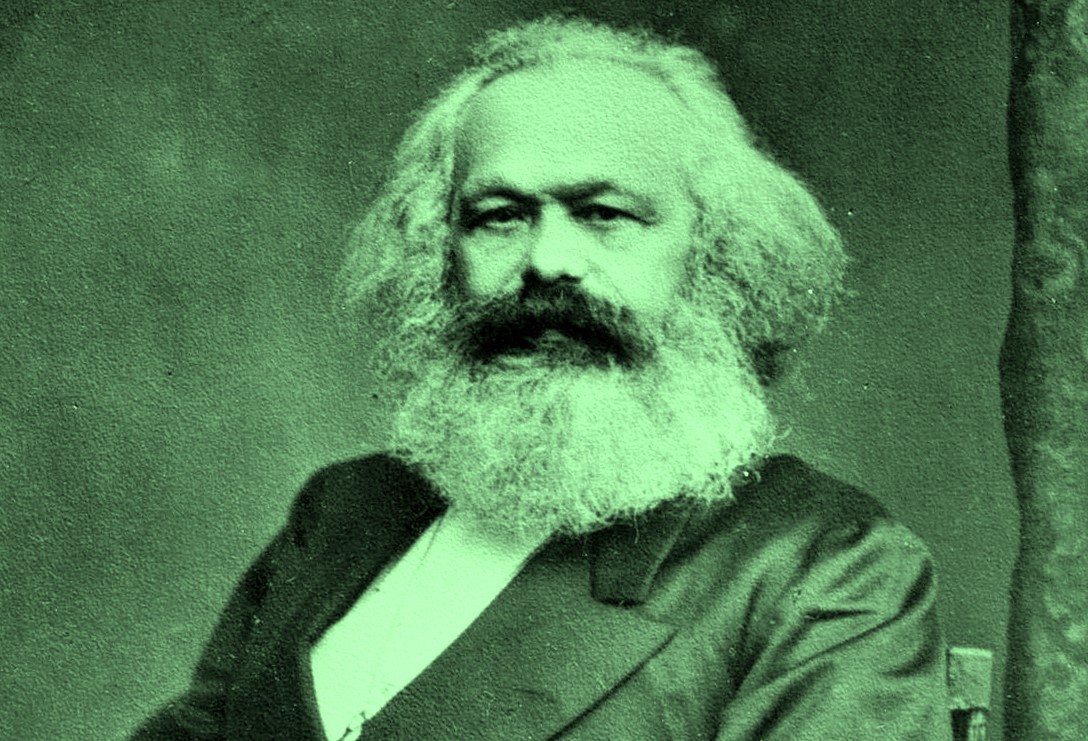

This is really giving Karl Marx too much credit. Granted, he was a brilliant thinker and analyst in the 19th century. But some of his followers hijacked his brand and launched the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, with generally regrettable results. In this century, however, he’s mostly forgotten — except by a handful of real Marxists. And to make him relevant again, his followers are redefining him as a 21st-century thinker.

A few years ago, a young Japanese Marxist scholar named Kohei Saito published Capital in the Anthropocene, a book arguing that Karl Marx was the first eco-socialist. To everyone’s surprise (including Saito’s), the book has sold half a million copies. It was popular among young people in Japan and made the author an unusual celebrity.

That book remains untranslated, but Saito has now given us a more rigorous and academic argument in Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism, written as much for his fellow Marxists as for general readers. It leads us into some debates that non-Marxists will find baffling, involving authorities unknown outside a small circle of the faithful. But it does give us an intriguing new perspective on our present crisis.

Using Marx’s long-unpublished notebooks from the 1860s and ’70s, Saito makes a persuasive case that Karl Marx was a work in progress, becoming a genuine environmentalist long before his death. From a Marxian perspective, Saito argues, many of our present climate and economic problems look solvable.

Not your grandfather’s Marxism

Before I get into the greening of Karl Marx, I should explain that this is not the Marxism that taught capitalism inevitably evolves into communism, and that capitalism’s enormous wealth should be redistributed to the workers who generated it. Under the new order, production of goods would increase forever. Technology would solve all problems.

That was the Marxism of the young Marx of the 1840s and ’50s, who was a great admirer of bourgeois capitalist productivity, especially in western Europe and the U.S. That made capitalism “progressive,” even as it expanded into its own self-destruction. Young Marx was a “productivist,” wanting every worker to enjoy the consumer benefits normally going only to the rich.

It was also the Marxism and "Amerikanizm" of the Bolsheviks, who under Stalin imported hundreds of American experts to build modern factories to enhance productivity and economic growth. All the Soviets really achieved was Chernobyl and the destruction of the Aral Sea, and a parody of western capitalism in which Communist party officials enjoyed a good standard of living and everyone else did not. Marx himself would have predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union from its own internal contradictions.

But as he continued his research into the 1860s, Marx began to reconsider productivity. He had thought that all value came from labour. Now he began to consider the natural world that the worker engaged with — and from which the industrial worker was increasingly alienated.

Nature as common wealth

The natural world, Marx now saw, was a kind of public wealth, shared and enjoyed by all. But he knew that public wealth could be seized by private individuals, as in the enclosures of the 18th century that turned common land into private property, and then robbed that land of its real value.

Deprived of their livings, those who had used the commons migrated to the cities and became the proletariat, toiling in the new mills and factories. The wealth they created was added to the private wealth of the rich, and the public wealth diminished accordingly.

Saito tells us Marx’s term for the relationship between humanity and the planet was “metabolism.” Capitalism had created three metabolic rifts in that relationship: first, the technological rift that enables capitalism to rob the land until farmers must rely on artificial nutrients to create profitable food; second is the spatial and cultural rift between rural and urban populations; third is the extension of the spatial rift to a global scale, with workers in the Global North enjoying an improved standard of living at the expense of workers in the Global South.

If Marx could see such rifts in the 19th century, we can certainly see them in the 21st. Farming is now agribusiness, and farmers like James Rebanks are seen as rebels for adopting “regenerative” farming practices. Consumers in cities have only the vaguest idea of where their food comes from, how it’s produced, and what’s in it. And Canadian workers certainly do better than their fellow workers overseas who may work for the same Canadian employers.

Marx reached many of his ecological conclusions after publishing the first volume of Capital. His colleague Friedrich Engels revised and edited the second and third volumes after Marx’s death in 1881, but he kept the emphasis on young Marx’s productivism. Even so, the later volumes have lines that might have come out of a news release from any B.C. environmental organization. For example:

“The development of civilization and industry in general has always shown itself so active in the destruction of forests that everything that has been done for their conservation and production is completely insignificant in comparison.”

Back to the future

In dropping productivism, Marx also dropped his Eurocentrism, which had made him think the whole world would follow the course of western Europe’s industrial revolution. Now he looked at ancient German and Russian communes, as well as Iroquois society, for clues to a future communist society. This research was lost on 20th-century Marxists, who were embarrassed that backward Russia was becoming communist before the more advanced industrial nations like Britain and the U.S.

Marx actually began to think Russia might escape capitalism altogether by adopting its old communal society enhanced by some modern technology. Saito calls it “communism in living,” like the communism of the family extended to the larger community. Soviet Russia was a ghastly travesty of such communism.

But a society that practiced communism in living would not be a high-tech, high-growth society, Saito tells us: “Through the communal regulation of lands and property, communism in living basically repeated the same cycle of production every year. That is, its long-lasting traditional way of production realized a stationary and circular economy without economic growth, which Marx once dismissed as the regressive steadiness of primitive societies without history. This principle of steady-state economy in agrarian communes is radically different from capitalism that pursues endless capital accumulation and economic growth.”

Common wealth, not private wealth

Saito argues that such communities would not be “ecosocialist.” “Ecosocialism,” he says, “like green capitalism, can be growth driven, but it will not be sustainable. Degrowth communism as a variant of ecosocialism aims for a post-scarcity society without economic growth. It aims to rehabilitate the abundance of common wealth against the artificial scarcity created by capital.”

Common wealth is not just old-growth forests and streams filled with salmon. It’s also what we share with our community, whether it’s food from our garden or the work needed to raise a barn. And it would be enough, Saito says: “[Marx] was convinced that once capitalism is overcome there would be sufficient to feed everyone. In other words, abundance is not a technological threshold, but a social relationship.”

From the viewpoint of 21st-century capitalism, degrowth communism might seem impoverished. You could never make enough money to take the family on a getaway to Cancún or Athens (and the Mexicans and Greeks wouldn’t welcome you anyway). But your minimal consumption of goods and services would put far less demand on the environment.

“Degrowth communism,” Saito writes, “produces less not only to increase free time but also to simultaneously lessen the burden on the natural environment. Certainly, the shortening of the working day is a precondition for the expansion of the realm of freedom, but the fairer (re)distribution of income and resources can also shorten the working day without the increase of productive forces. In addition, by cutting down unnecessary production in branches such as advertisement, marketing, consulting and finance, it would also be possible to eliminate unnecessary labour and reduce excessive production as well as consumption. Emancipated from the constant exposure to advertisement, planned obsolescence and ceaseless market competition, there would emerge more room to autonomously ‘self-limit’ production and consumption.”

Dangerously subversive

This may sound pretty radical, especially to those who think our present standard of living is sustainable if only we convert to renewable electricity. Saito’s green Marx sounds as dangerously subversive as the old red one did a century ago.

And really, does it matter if some 19th-century thinker turns out to be eco-friendly?

Saito thinks it does. He offers his green Marx as part of a “Front Populaire” of groups determined to reduce emissions and overthrow the system that is burning the world down. He may have a point. Marx’s analysis of capitalism has dated very little, especially as Saito presents that analysis. It’s all very well to complain about the fossil-fuel industry, but Marx helps explain why capitalism could not survive without fossil fuels.

That’s why we subsidize oil and gas to the tune of $7 trillion a year — because if we didn’t, gas would be $50 a litre and a loaf of bread would cost a hundred bucks.

Understanding capitalism from a Marxist point of view could help give us a clearer sense of the system we find ourselves trapped in, and some clues on how to dismantle the system without bringing it down on our own heads.

And if we also start looking at societies that changed their systems when they no longer served their purpose, we might actually find a way out of this mess. ![]()

Read more: Books, Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: