Manabu Ikeda recalls the moment in 2011 when he turned on his computer and saw headlines and images showing the most devastating earthquake and tsunami in the recorded history of Japan, his homeland. Just two months into an emerging artist fellowship that brought him to Vancouver, he was enjoying life on the peaceful West Coast, and the disconnect between his own situation and the catastrophe unfolding in his faraway homeland unhinged him.

Ikeda remained glued to his computer, anguished and helpless as he watched cars and houses being violently upended and hurled around and swallowed by the forces of nature. “I couldn’t help but feel like I was watching the whole of Japan sinking, and my body just trembled,” he remembers. “It was soul-crushing.”

And then, the pain and terror inspired him to create some of the most heart-stopping artworks now exhibiting at the Audain Art Museum in Whistler. Arranged and curated by Kiriko Watanabe, the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky curator at the museum, Flowers from the Wreckage is Ikeda’s first solo retrospective in North America.

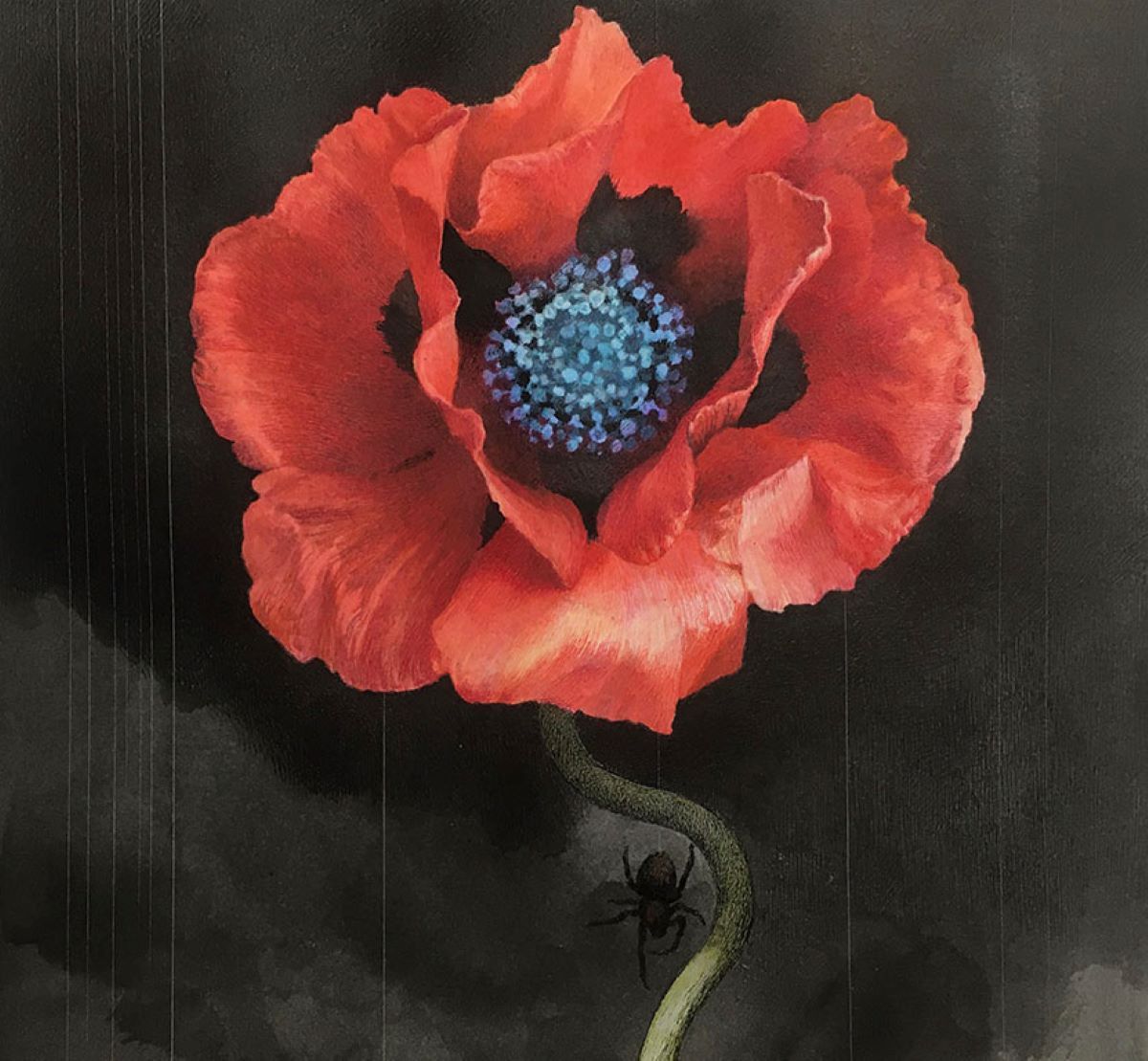

Working in the old-fashioned media of pen and ink on paper, Ikeda creates astonishingly detailed renderings that are enrapturing and terrifying all at once. The exhibition title, Flowers from the Wreckage, hints at that duality: like the works of 15th century Dutch master Hieronymous Bosch, or our own Canadian contemporary, Edward Burtynsky, Ikeda reveals the terror beneath the surface of our placid lives and compels us to watch and, in some strange way, admire it.

His imagery is hyper-realistic, but often strays far from the laws of physics. “I don’t believe in drawing more realistic depictions of disasters, when such images are readily available through the media,” he says in a Zoom interview from the museum, where he is working as an artist in residence until early September. “I would like my depictions to be beautiful, to have an element of humour that captivates people. And with these images, I’d like to convey messages.”

The recurring message in his work is how when we see beauty, we often fail to notice the dark underlying reality. We see flowers blooming, oceans roiling, forests covering the landscape. “And yet when you look more closely at these images, you discover what is really happening: not things of beauty, but activities that are harmful, that hurt people, that hurt the environment,” notes Ikeda. Forest fires, nuclear radiation, even the coronavirus cleverly disguised as the stamen of a vibrant red poppy.

One of his most important works, Meltdown, was conceived while Ikeda was still reeling in shock from the 2011 catastrophe in Japan. The four foot by four foot pen-and-ink drawing is nominally about the Fukushima Daiishi nuclear reactors severely damaged by the tsunami. The rendering depicts what looks like an inverted glacier crowned with a dozen mangled industrial and nuclear plants fused together, sliding down a forested slope. But it could be a visual metaphor of all the past and future catastrophes, natural or environmental or military.

The idea for Meltdown took root in Ikeda’s mind while he was visiting the lakes and glaciers of the Canadian Rockies. “In this work, heat and pollutants are constantly being emitted from the industrial areas that are densely packed around the glacier, and they gradually cause the glacier to melt with polluted water and collapse into a beautiful lake,” he writes, concluding with a quintessentially Canadian detail: “A moose is staring at humans who have no choice but to escape with gliders and parachutes.”

If you inspect the work up close, you can see specific imagery inspired by Vancouver as well: the dozens of boxy little houses hanging ominously from the mass were inspired by the cluster of barnacles around the piers of the Granville Island docks. The blobs of lurid yellow in opposite sides of the glacier are a nod to the North Shore waterfront’s longstanding piles of sulphur, a byproduct of natural gas processing. Even the Grouse Grind gondola makes a cameo appearance. It’s quite the bouillabaisse of hedonism and horror.

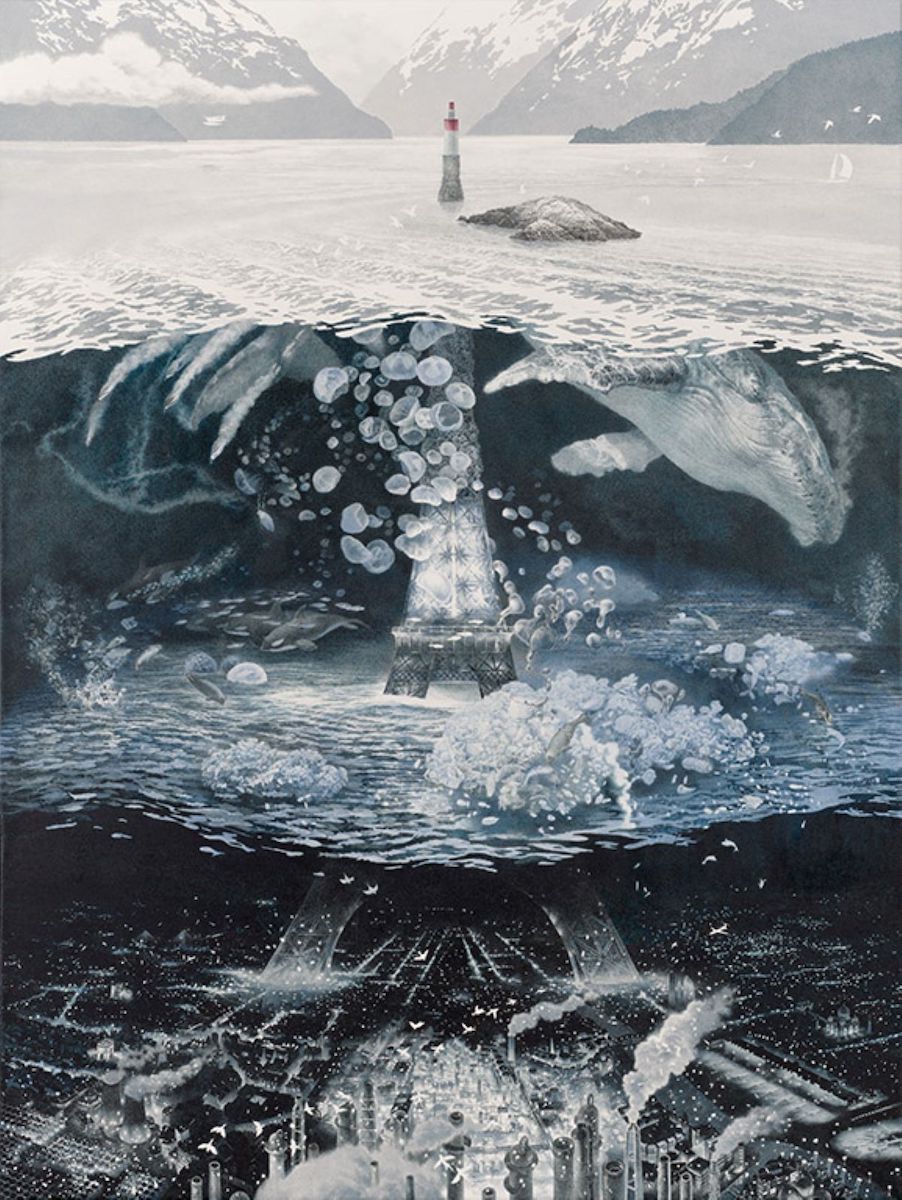

Ikeda’s other renderings include Three Surfaces, inspired by the ocean and mountain view from the West Vancouver home of museum founders Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa. In an unlikely fusion of subject matter, the Eiffel Tower appears to be poking up through the waters of Howe Sound in a clever illustration of our two cities’ legendary iconography.

The lowest surface depicts the feet of the Eiffel Tower in a dark, speckled backdrop that could be the nocturnal City of Lights — or the deep ocean now filling with microplastics. The middle surface shows the tower in a watery backdrop with abstraction of dolphins and amoeba swirling around. The upper surface shows the Eiffel Tower’s spire transformed into a buoy poking through the water beside one of the area’s thousand small islands.

If you’re a bright-eyed optimist, the artwork depicts the shared joie-de-vivre and connection between Vancouver and Paris, where so many of us ache to visit and revisit. If you’re a cynic, or a realist, you can perceive the price we pay for our wanderlust in carbon emissions and environmental degradation.

Even those pieces that aren’t directly depicting this region still seem to be about this region: chalk it up to the fact that his interests and concerns — cultural erosion, COVID, the impending Big One, environment degradation — are also our concerns.

The 2019 drawing Green Expressions is not specifically drawn from a forest in the B.C. Interior, but it easily could be. When I first gazed at it, I saw a robust and endlessly verdant forest. Later, when I returned for the proverbial “closer look,” I saw something startlingly different: a few of the trees look like flailing human bodies. Then I looked even more closely: almost every individual tree is evocative of a human head — some childlike, some smug-looking, some anguished. The entire rendering transformed from a pastoral landscape into a Boschian hellscape, right before my eyes. That makes it all the more captivating.

Then I asked myself: How could I not notice this the first time I looked at it? For the same reason that we cannot directly see the impact of our driving, air travel, plastic bags, online shopping on our forests, rivers, oceans, soil. Because we are too far away from it all, and we cannot or will not look closely enough.

‘Flowers from the Wreckage’ exhibits at the Audain Art Museum in Whistler, Thursdays through Mondays from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. The artist will be in studio at the museum on Thursdays, Friday and Saturdays, from 3 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. until Sept. 4. Museum guests are encouraged to come and witness the artist’s talent and learn more about his techniques. ![]()

Read more: Art, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: