In its deep forests, freshwater streams, bogs and intertidal zones, an incredible diversity of habitats and wildlife can be found in Stanley Park.

Located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh Nations, the park is a massive 400-hectare urban forest on the edge of Downtown Vancouver, best known around the world for its waterfront perimeter path, the seawall.

But there’s so much more to it than that.

What keeps it all rooted — to be quite literal — is the tree and plant life, although some species found in the park can do more harm than good.

That's where the Stanley Park Ecology Society comes in. The society is a non-profit organization that promotes awareness of and respect for the natural world through collaborative leadership in environmental education, research and conservation.

In a joint operating agreement established with the Vancouver Park Board in 1997, the society became the primary provider of land-based education interpretive services in Stanley Park. The society's role in the stewardship of Stanley Park is undertaken through a combination of education, research and conservation in action.

And while coyotes might grab the headlines, a crucial part of active stewardship involves not just fauna, but flora too.

“What I’m really interested in is how a lot of the ornamental, non-native plants can sometimes escape gardens and become invasive plants,” says Marisa Bischoff, who is a conservation technician with the society.

Her typical workday might include hopping on a bicycle at 5 a.m. to do a bird survey around the park, wading through Lost Lagoon (known as Ch’elxwá7elch in Skwxwú7mesh) to get water temperature readings, or set up a swallow's nest box. She has a passion for restoration and is interested in the natural intersection of decolonization and conservation.

Indigenous plants

The roots of Stanley Park — its greenery — is made up of all kinds of plants. “Native” or “indigenous" is a term to describe plants endemic or naturalized to a given area in geologic time. This includes plants that have developed, occurred naturally, or existed for many years in an area.

Stanley Park (the traditional Indigenous name, X̱wáýx̱way, refers to a village site near what is Lumberman’s Arch today) is home to at least 1,500 native species of fungi and plants, as well as invertebrates, birds and mammals.

Ornamental plants

“Ornamental” plants or “garden” plants are plants that are grown for decorative purposes in gardens and landscape design projects.

Examples of these in Stanley Park would be the Rose Garden (blooming from 3,500 bulbs initially planted in 1920), the Rhododendron Garden, giant weeping willows, tulips and cherry blossoms.

They look pretty, they’re great for Instagram moments, but they’re not indigenous to the park.

However, they don’t really do much harm being there.

“A lot of the ornamental plants are not an issue for escaping,” says Bischoff. “I have not heard of any cases of the roses escaping into the forest for example, but there are some species that are considered invasive by some that are still planted in a lot of gardens.”

Invasive species

An “invasive species” can be any kind of living organism that is not native to an ecosystem and causes harm.

“Basically an invasive species could be a plant, animal or other organism that was introduced into a new ecosystem where it was not originally from, either intentionally or unintentionally and in most cases, if not all cases, by humans,” Bischoff explains.

Many introduced species are present in Stanley Park, including 89 invasive species of plants and animals confirmed in an October 2020 survey.

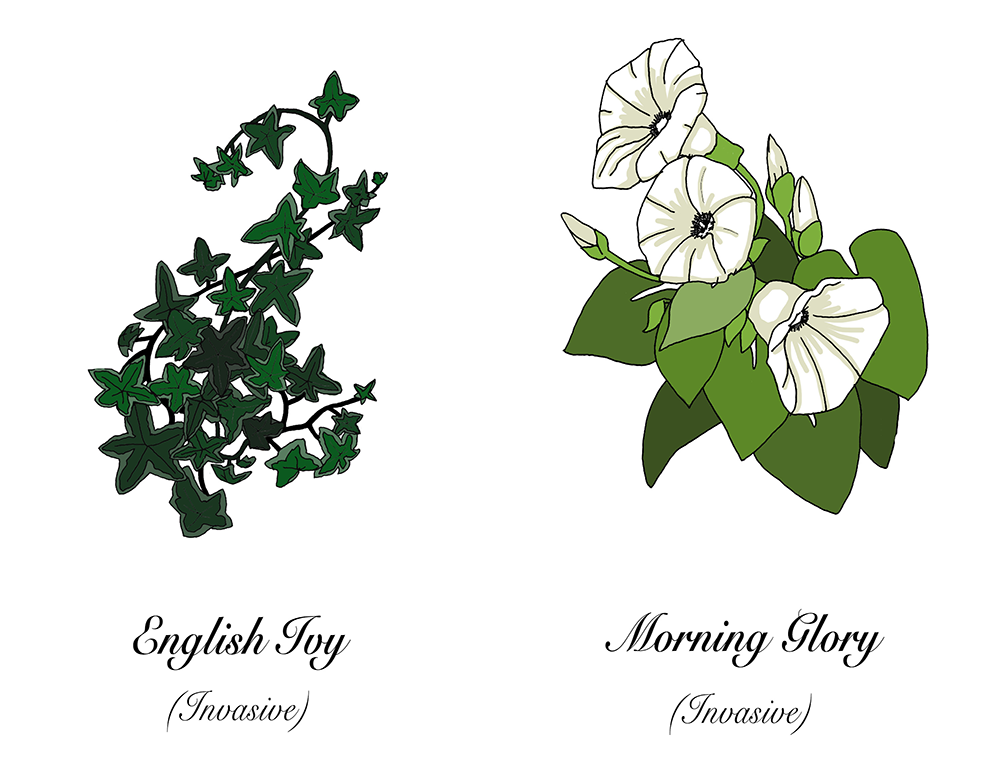

One example Bischoff gives is English ivy, which can still be purchased locally at some garden centres.

Bischoff says that if you’ve spotted it up close in nature, you’ll notice how much it can really take over a patch of ground on the forest floor or climb up trees to create a cathedral of ivy without any control.

“I still like a garden as much as the next person, but it’s about determining where they would be best placed. I think there’s a lot of untapped potential in urban gardens or forests where you can increase biodiversity by planting native plants.”

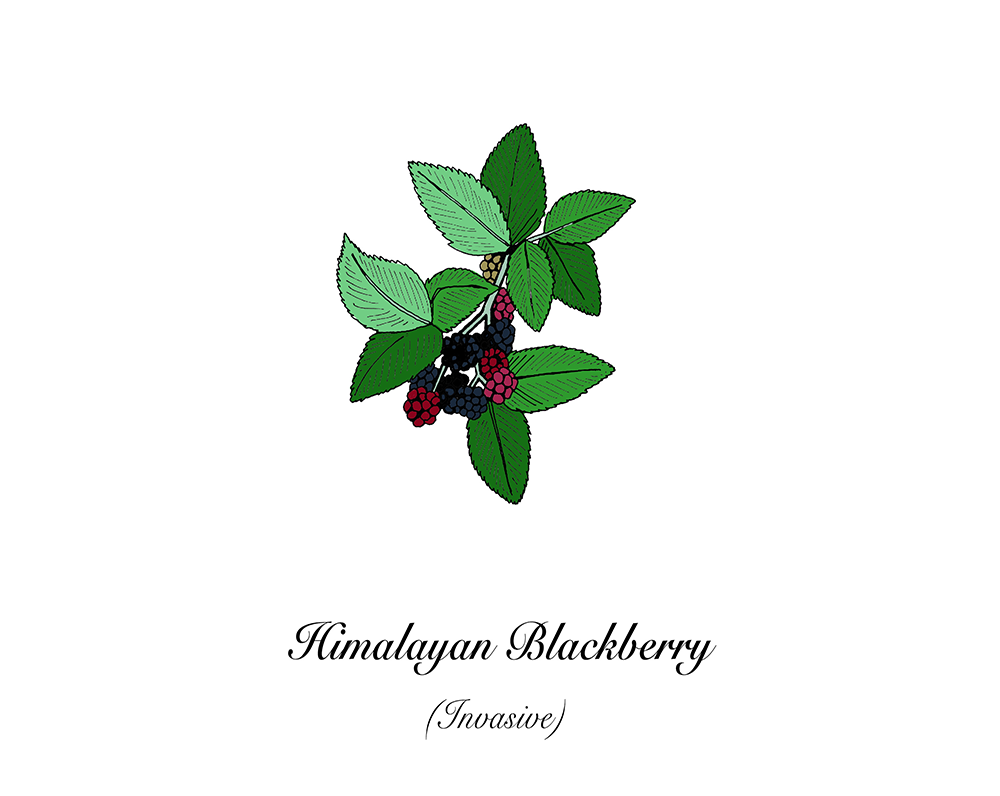

The Stanley Park Ecology Society has a full volunteer squad, aptly named DIRT, or the Dedicated Invasive Removal Team, that meets several times a week to carefully and properly remove invasives such as English ivy or Himalayan blackberry. The volunteers focus on areas of ecological significance and work patch-to-patch in the park.

Bischoff says that what they’re concerned about at the society is how these invasive species out-compete native species for space, nutrients in the soil and sunlight.

“They don't have any natural or native predators or pathogens that they evolved with over time here, so it’s very difficult to control them once they get out of hand or once they establish,” she says. “Some species like Himalayan blackberries or English ivy tend to form monocultures in some areas when conditions are right, which causes a decrease in the biodiversity of different plants that can grow in that area because it just takes up all the space.”

Not only do invasive plants spread like wildfire, they suppress the growth of native tree species. However, the society has found that in some cases, indigenous plants can find their way back, sprouting back up from the soil where invasives were removed.

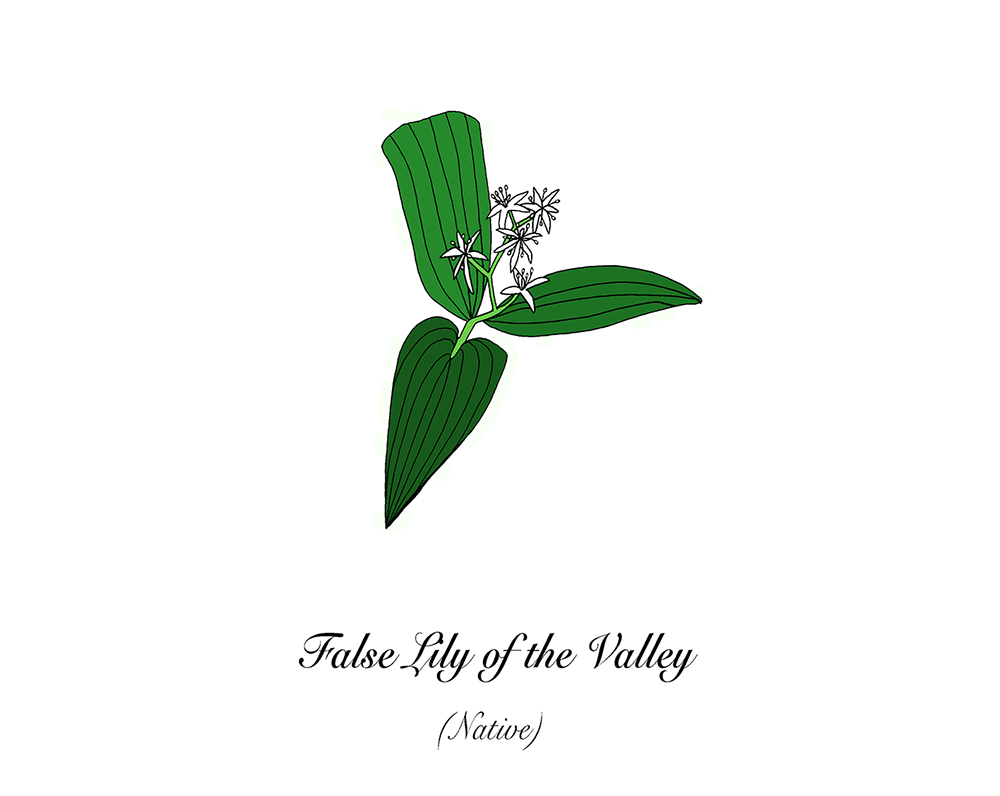

“A lot of times we’ll see native plants come back up from the natural seed bank. Around Beaver Lake, [known as Áx̱achu7 in Skwxwú7mesh], there was false lily of the valley coming back up where they took out English ivy. Same soil conditions, same everything, but they just needed that chance to push up,” Bischoff says.

Once the invasive roots are pulled and cut back, DIRT also came up with a clever way to upcycle this waste. The volunteers make natural fences (instead of using plastic) by bending and twisting Himalayan blackberry stalks to add another level of protection to sensitive areas around the park. Everything else is carted away by the park board.

However, it’s not just the plants that benefit. A study by Caroline Astley in 1997 found that the overall diversity of breeding birds decreased significantly in areas where Himalayan blackberry was the dominant understory shrub. She found that somewhere between five and 14 species of birds — including the spotted towhee, American robin and the Anna’s hummingbird — select blackberry for building their nests, however that number increased to more than 22 species of birds in areas where a more natural composition of native shrubs and trees was present.

First Nations perspective

Candace Campo, from the Shíshálh First Nation, is an anthropologist, educator and knowledge keeper dedicated to preserving the culture of the Shíshálh First Nation and the territory its members occupy.

Along with her partner Larry Campo, from the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh First Nation, they operate Talaysay Tours, which hosts Indigenous plant walks in Stanley Park and on the Sunshine Coast. They’ve partnered with the Stanley Park Ecology Society on occasion to host walks and talks, and their team shares their extensive knowledge with the public about species that have been around for many millennia.

Nature is inherently all about balance and for almost every invasive species, there is a hearty indigenous plant that can take its place in your garden — and the local pollinators will love you for it.

Campo pointed out some differences between invasive species and indigenous plants, and offered up some Earth-friendly options for your own garden.

Invasive: English ivy and morning glory

Ivy is commonly planted to provide ground cover in commercial or residential landscapes. Unfortunately, it quickly forms a dense mat that suppresses native plants. Morning glory is a vine that has pretty flowers, but it will wrap around other plants and is very difficult to get rid of year after year. You have to get it out by the root, as any fragment left will regrow.

Instead try: False lily of the valley

Native to B.C. and very friendly to pollinators, this plant is a much healthier and friendlier groundcover than English ivy. It produces clusters of tiny white flowers mid- to late summer that are replaced by glossy — but poisonous — green-and-purple to red berries in late summer.

Invasive: Himalayan blackberry

In addition to taking over space for native species, Himalayan blackberry also creates a monoculture — an area where only one plant thrives. It has a berry only from June to August, whereas the whole community of different native plant bushes that bear berries will run from early March to early September, so there’s more of a variety of production, for longer.

Instead try: Nootka rose, salmonberry, thimbleberry

Nootka rose has soft pink, edible flowers which Campo says are a source of natural perfume. In the fall, the rose hips were traditionally harvested as they are great for digestion and are an amazing source of vitamin C. It grows in a thicket and can stabilize banks along waterways.

Salmonberries are the first berries to come out in the season, and since they do resemble salmon eggs, you can even use them as fishing bait. Campo is always very excited to spot these.

“Even before we enjoy the berries, we get to enjoy the shoots. They’re very delicious! They’re sweet and you peel them like a banana. They have a thin red skin with pricklies but you can navigate around those.”

Much like the salmonberry, young thimbleberry shoots are a tasty treat in the springtime as well. These berry bushes have white flowers and light red berries with a hollow core, like raspberries, making them easy to fit on the tip of a finger like a thimble. The leaves are very soft, and Campo says if nature calls out in the woods, they’re the best substitute for toilet paper.

“I grew up picking berries and I value them immensely,” Campo says about those who might consider foraging. “But you need to consider the needs of nature. The animals and birds need this food also and rely heavily on them.”

Visitors to Stanley Park are discouraged to pick, harvest, forage or eat any plants — even if you are able to correctly identify them.

Invasive: English holly

While it might be a festive holiday staple, according to the Invasive Species Council of Metro Vancouver, English holly is a “notorious nutrient hog.” It creates deep shade under its canopy and suppresses germination of native species.

Instead try: Oregon grape and salal

If you simply like the look of holly in a garden, opt for Oregon grape instead. It’s a tall evergreen plant with spiny leaves that turn purple and red in the winter, with bright yellow flowers and blue berries. Traditional uses include eating the berries, in a mix with salal for a sweeter taste, or using the roots, stems and bark for dyes or medicine.

Over winter months, according to Campo, salal played a very important role in Indigenous life when it came to ensuring everyone got enough antioxidants and vitamins.

“Salal berry functions as a binder, it’s got natural pectin in it, so when we would dehydrate it and make berry cakes and berry leather, it is the salal that held all the berries together. Some people say it’s a moderate flavour but I find it absolutely delicious!”

Campo says it’s considered a superfood, and it’s even better than organic blueberries when it comes to nutrients.

Let’s talk about trees

Aside from indigenous plants, there are many species of trees found in Stanley Park that are integral to the ecosystem, which has included humans for thousands of years.

Coast Salish communities used broad leaf maple to make tools and paddles, and also exclusively to make spindle whorls for spinning the mountain goat wool and woolly dog wool.

Campo calls the alder the “nurse tree of the forest,” since it can live 60 to 80 years and when it dies, it releases nutrients back into the soil so the next stage of the forest can grow.

“We still use this tree quite extensively for cooking,” she adds. “It’s extremely aromatic. When it burns it creates a lot of smoke, but that smoke is very savoury in that it infuses flavour into your food. When I was younger we would gather the bark of the Douglas fir for the Elders, for their wood stoves. It burns slow and gives off exceptional heat.”

When there’s an incision made in the tree, sap flows to that spot so it would be collected. “It heals the tree, but it also heals humans and animals quite profoundly,” Campo says.

If an incision was made, it was referred to as the pitch pot method and the resin was collected to use for both medicinal and technological needs — including salves for healing cuts, infections and gum disease.

The resin would further function effectively as fire starter and caulking for canoe repair.

The branches of the vine maple would be used for non-permanent shelters, for people hunting or on the move. They would be bent down and latched to the ground, providing cover. When they woke up they would unlatch the branches and be on their way with no harm to the tree.

Weeping willows are not native; they’re planted mostly for aesthetic value, but they help reduce erosion, anchoring the shoreline of Lost Lagoon. When they fall, they provide a rich habitat.

Pacific willows look like tall shrubs and grow along the shores of Lost Lagoon and Beaver Lake. They create shade over the water and provide habitat for wildlife.

When they’re younger, they emit a chemical that beavers find unappetizing, but when they’re more mature it goes away and beavers will use them for building dams.

The Tree of Life

“They say our forest started to emerge after the last ice age, around 6,500 years ago and the first trees that emerged were the birch and the Douglas fir,” says Campo, whose Elders encouraged her to go into archaeology for her community. “Around 5,000 years ago, the cedar tree started to exist in this region.

Nonetheless there were areas called refugia where there were openings and breaks in the ice age and one of them, believe it or not, was in Saltery Bay.”

It was there she did a study at one of the Sechelt Nation’s sites which dated back 9,500 years.

“I give that context because it’s how we teach about nature,” she says. “The cedar tree absolutely provided us everything: transportation with our cedar dugout canoes, with our larger elaborate winter longhouses for potlatching — as big as a soccer field and sometimes three, and our clothing. When it was woven it was modified and pounded to be soft to the touch.”

The planks would be steam-bent for making boxes, which would allow them to store immense amounts of food and nutrition.

“We did not survive the winter, we thrived in the winter. It is understood that Indigenous people in this region averaged five to seven hours of work [per day] and had all of that remaining time to develop art, culture, spirituality and come winter it was the potlatch.

"So we had all of our food, and not only did we feed ourselves, our own villages and tribes, but we would invite other tribes to come live with us for entire winters. Thousands of people would come live with us and we would have the capacity to feed them.

"During that time we built really strong relations with each other, we built cultural protocols, environmental and ecological protocols, and we learned each others’ language.”

The cedar tree helped her community’s material culture develop in the last 5,000 years and now she says it is believed by scientists that it’s going to become extinct within 100 years. “For me, instead of accepting that as a fact, let’s talk about this and let’s make sure that doesn't happen.”

What can be done about invasive species?

In some instances, invasive species can spread through seed dispersal, hitching a ride with birds from places to place, but more often than not it’s humans who are leading the charge.

Here’s what you can do:

- Reintroduce native species to your garden. A great example of this is the Stanley Park Community Garden located at the foot of Robson Street below Lagoon Drive and Chilco. Neighbours and volunteers have cultivated a pollinator friendly native plant garden over the last 20 years. The plants are labelled and they also have bird boxes and bee boxes for the native mason bees.

- If you’re up for getting your hands dirty, consider joining DIRT. You can make an important contribution to habitat conservation and restoration in Stanley Park. Email them for further details.

- Learn about plant species through the Stanley Park Ecology Society educational programs (for all) and day camps (for kids). Education is a key component. Visit their website for more information.

- Join one of the Talaysay Tour experiences to learn more about the land and its Indigenous history. Discover the various culturally authentic experiences available at their website.

- Observe. Next time you’re in the park, take a moment to see the forest for the trees, stop and smell the Nootka roses, touch the soft leaves of a thimbleberry and admire the brightness of fresh salmonberries. Reflect on what has been there for thousands of years, what poses a threat, what serves a purpose and what, quite simply, might just look pretty.

The traditional Indigenous place names used in this story are from the hǝn̓q̓ǝmin̓ǝm̓ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim languages. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: