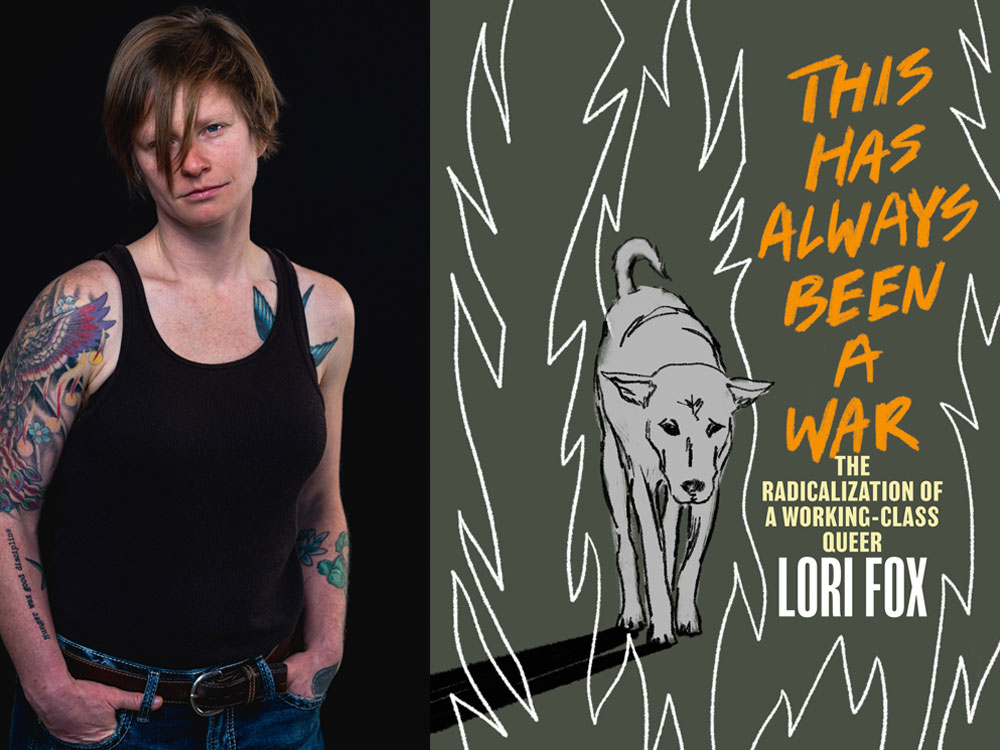

[Editor’s note: 'This Has Always Been a War' features essays about Lori Fox’s work and family life — highlighting the difficulty of the banal, and the banality of the difficult. After living through a childhood marked by trauma, Fox must make their way through adulthood without the family connections they’ve left behind in order to find peace and safety and freedom — in a world that is often openly hostile to Fox’s gender, and queerness, and where it is difficult to make the fruits of labour align with the rising costs of rent. The following excerpt comes from 'Other People’s Houses,' an essay that explores Fox’s search for stable work and stable housing in the same place, at the same time.]

By spring 2017, I was running out of money.

I couldn’t find work or afford my sublet in Montreal anymore, so I took a job on Salt Spring Island as a farmhand. I piled back into the car with my things and my dog, thinking once again that I was headed, if not for something better, then something stable. In my head, I thought the warmer climate would make things a little easier. At least, I reasoned, if things didn’t work out, I could sleep in the car or camp for far longer than I could in the East or the North.

I drove through the upper United States in March. There was wind and rain. There was snow. There was ice and impossible mountain passes. I was to start at the farm on the first of April and, finding myself held up in the Bitterroot Pass of Montana in a terrible ice storm, sleeping in a tent, I waited for a break in the weather before driving from Butte, Montana, to Vancouver, British Columbia, some 1,000 miles straight, on nothing but ramen, truck stop coffee, a pack of Marlboro reds, and a beer every 300 kilometres.

I was 31 when I arrived on Salt Spring Island. Although the farmers were kind and the food excellent — fresh greens and fruit, after being in the North for so many years, seemed a delicacy — there was no running water or electricity in the cabin I was provided. There was an old futon mattress, which was mildewed and damp. The wood stove, improperly installed, leaked smoke dangerously. The work was gruelling. One week, I did nothing but pull weeds from a blueberry field in which nests of hornets and mildew had taken root, tearing out piles and piles and piles of what locals call “cooch grass.” I woke in the morning with my hands so stiff and swollen I couldn’t make a fist. My friends tried to heal them by wrapping them in plantain and mullein overnight.

My first week on the farm, anticipating how little my $500 a month stipend would buy me, I started a side business. I had always been resourceful and good with my hands, traits that my time in the bush and working construction had only refined, so I advertised myself as a handyperson for $20 an hour.

In a week, I had more clients than I could handle and had to pull the ad. Soon, I was working eight- to ten-hour days on the farm and another three to five hours of manual labour in the evenings — building fences, splitting wood, moving furniture. All the while, I continued to write news stories and essays periodically for Vice online. I grew thin, wiry. I was hungry all the time, but when I came home at night and lay down, tired down to my bones, lips sunburned and peeling, I was often too exhausted to cook, let alone eat. More than once I ate fresh, raw duck eggs just for the calories.

It was during this time, however, as I roved the island, that I noticed something strange. There were all these big, beautiful houses — so many windows! So many bathrooms! Such gardens! — but only two, three, four people living in them.

There were few apartments, and people rented anything and everything in their desperation: unheated cabins, RV campers, shipping container “houses.” One person I knew even rented an old van propped up on cinder blocks in someone’s backyard. I met people who lived on sailboats and people who lived in their cars year-round — not only the usual roamers, but people with jobs, people who had dogs, people who even had kids.

Most people I knew worked on farms and were rarely paid full price for their labour. Instead, they were offered room and board and a stipend, which meant if you wanted to quit you usually had to leave the island, because there was nowhere else to live that poor people could afford. There were homeowner associations and community groups that tightly controlled what kind of housing could be built, and where, and how many people could live there, in order to maintain the “character” of the island — code, of course, for keeping the trash out. There were secret, quasi-legal housing units which, when they came on the market, were advertised only by word of mouth. There were innumerable houses in which no one actually lived, instead hosting a rotating cast of off-islanders paying a premium for their luxury accommodations through Airbnb.

Basically, if you wanted to live on Salt Spring and were not rich, you had to work for someone who was. They’d give you a place to stay so that they could make money from you, either by your direct labour, or by renting something to you that, elsewhere, would not be thought fit to live in. You didn’t have a place to live unless you lived to take care of other people’s property, paid for other people’s mortgages. It was an island of the rich and their servants.

By June, I saw the trouble I was in; at the end of September, as the growing season ended, my contract with the farm would finish up, at which time they would require me to either move out or begin to pay for lodging. Locals had told me that work was scarce in the winter — the tourists were all gone, many shops were closed — so it would get even harder to make a living. My meagre stipend barely covered the insurance on my car and groceries each month, so if I wanted to save money, I’d have to keep freelancing and keep up the handyperson business, which, compounded with the work I was already doing, meant maintaining an absolutely brutal pace. As the cafés closed in the fall and winter, I’d have fewer places to work out of; writing would become harder, and the ferry off island was expensive.

If I stayed, I would likely be trapped until spring, unable to afford to leave.

I knew there were good burns from the year before in the B.C. Interior, where forest fires had summoned morels. The price, I knew, was low that year, but I was a seasoned picker; working alone, I could make a go of it.

A younger, less-cautious me might have waited it out, because I liked the climate and I liked the people, but I saw it coming: the cold, wet winter alone in the cabin or in my car, in either case without power or water or internet.

So I left. Not because I wanted to, but because it felt like the only way to survive long term. I quit the farm, left the island, with its smooth-skinned arbutus trees and its blackberries growing in fist-sized clusters and its tiny Sitka deer, tame as chickens, and went back out into the bush.

And there I was a second time. Homeless.

I worked the burns, first the Elephant Hill fire, and then, when that dried up, the Whiteswan fire, near Canal Flats in the Kootenays. When the season ended, I worked on farms in the Okanagan picking fruit, and then in Salmon Arm, picking prickly lodgepole pine cones, which would be used to start seedlings for tree planters. Often paid in cash, I saved my money in a coffee can hidden in the back of the car — bills bound together with a paper clip in a President’s Choice dark roast coffee tin.

When the season ended and it grew cold, I turned the car north and went up the highway again, back to the last place I had been safe or stable, the last place that had felt like home: Whitehorse.

There was nothing else to hope for, but also nothing else to lose.

Excerpted from ‘This Has Always Been a War: The Radicalization of a Working Class Queer’ by Lori Fox. Copyright © 2022 Lori Fox. Published by Arsenal Pulp Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: