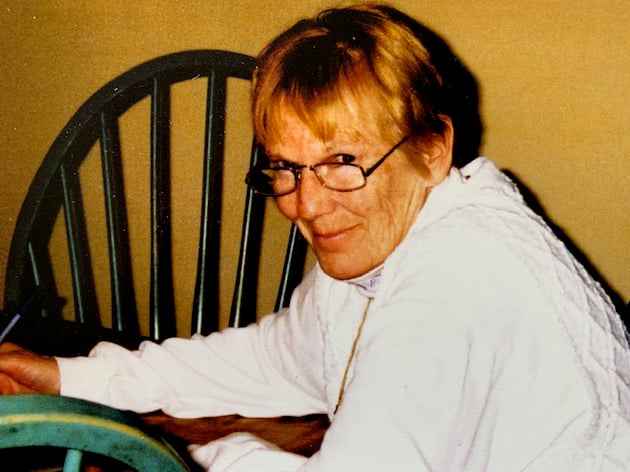

We are sitting on the deck, overlooking banks of dry hills that run into Lake Windermere. My mother is fanning herself with a folded section of the newspaper in one hand, holding a glass of wine in the other. Several books are stacked on the table beside her. Despite the late summer heat, she’s wearing black baggy pants with a white turtleneck and a multi-coloured vest. The large pockets of the vest are bulging with tissues and Tums. Her eyes are clear blue, her face strong and creased, accentuated by her bright ruby lipstick. Her hair, always unpredictable — today shades of dyed auburn — slightly matted at the back. Looking out across the landscape, she takes a sip of her wine, her lips leaving a red smudge on her glass. She puts the newspaper and glass down and dramatically sweeps her graceful hands towards the landscape.

“When I kick off I don’t want to be buried,” she says. “Cremate me and spread my ashes on that hill out there, looking over the lake.”

“OK,” I say, “you realize that’s not even our property, right? It’s the neighbours’. Plus I don’t even think that’s legal.”

She throws her head back and starts laughing unabashedly.

“Jesus, mom,” I mutter, but her happiness is contagious and soon I am laughing as well.

It’s hard not to be swept up in her joy, after all. The sun is setting — the horizon a fading streak of crimson, but we stay longer, talking and laughing. She has the gift of the gab, my mom, and humour.

We all have mothers. But none like Frances.

Her wardrobe was an adventure. She shopped at thrift stores and loved garage sales. Frances was a pioneer of reuse and recycle before it was the norm. My siblings and I never knew what get-up she would show up in. Even she would have a good laugh at some of her fashion choices, delighted with the reaction she got from us.

The most memorable one is what she and I would come to refer to as the “Friar Tuck” outfit. I was picking her up after her volunteer shift at the hospital, sitting in the car waiting for her to come out. It was always a surprise, seeing what she was dressed in — sometimes hilarious, sometimes downright embarrassing. Out she came, wearing mustard-coloured baggy pants and a sandwich board matching top, pulled over a turtleneck. The kicker was the rope belt. Literally. Rope. For a belt! I joked it was as if Friar Tuck had broken the rope while ringing the church bell and used it for a belt. I started laughing before she even got in the car. She did a little jig as she got in.

“Too much?” she asked innocently. We howled in laughter all the way home.

She once gave me a photocopy she had made by placing two photos of her younger self side by side on a sheet of paper. In one photo she’s wearing a bikini and the other a nun’s habit. She scribbled beside it: “from the sublime to the ridiculous.” It’s true. My mother was a nun before she met my father. She entered the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto in February 1950. She was 20 years old. The novice name given to her was Sister Peter Claver. She started having panic attacks, and they asked her if she should rethink her calling. She left the convent before receiving her vows. Shortly after, she met and married my father.

When she gave me that picture, I asked her what the attraction was for her in becoming a nun.

“From a very young age I wanted to become a nun. The order and simplicity of that kind of life was attractive to me,” she said.

The home I grew up in was not simple and was completely devoid of order. My mother had six kids within 10 years, constant financial instability, no family support and both her and my father were “dreamers,” she confessed to me years after they divorced. She was a haphazard housekeeper — frozen clothes standing like frosty scarecrows all around the kitchen in winter, thawing into puddles on the linoleum floor. She didn’t cook. My father made our meals. My mother created backyard circuses with tents of bed sheets.

Years later, when I had my own family and she came for visits, I would ask her to “please step away from the kitchen.” Her previous cleaning efforts duly noted — the kitchen sink filled with cold water and cigarette butts floating amongst heaps of dirty dishes — she was happy to relinquish any pretence of cleaning up or helping cook. These mundane tasks did not interest nor come easy to her. As a young woman, it must have been overwhelming, trying to keep sane in the chaotic mess that was our family. But she was creative and resourceful.

Books were Frances’s entertainment. She was a prolific reader and passed on her love of literature to all of her children and most certainly countless other people too. I grew up in Kenmore, a small rural town in Ontario. The closest city, Ottawa, was an hour away. There were no libraries or museums or theatres, so Frances set up a makeshift library in the town hall to bring some enrichment to our community. She collected hundreds of books and sorted them into categories, laid out on tables that people could peruse and borrow from — any amount they wanted. I remember hiding under the tables while she helped people pick out books she thought they might like.

By the time I was in Grade 1 my parent’s marriage had reached a breaking point. They agreed to separate, my mother hoping distance “would make the heart grow fonder.” She moved my two youngest siblings and me to live with her in Ottawa, while my three older siblings stayed to live in the country with my dad. My mother thought this set up might save their marriage but it didn’t work out that way. Every now and then, there would be a spark of enthusiasm — a sign that dad was ready to move to the city. This would bring on the futile motions of making plans, my mother excitedly chatting about possible neighbourhoods they could look at where we could all live together. It was always short-lived, ending in fights and disappointments. Eventually my father met someone, ending the possibility of the reconciliation that my mother was hoping for.

When her divorce was final Frances was devastated and depressed. She was 47 and wanted to start a new life. She told me she was searching for something that would “shake up her emotions,” so she joined a Canadian organization that ran children’s schools in underdeveloped countries. This was the late 1970s, the time of Mother Teresa’s miracles and Gandhi’s hunger strike. Frances idolized both, so she went to work in India at a school for unwed mothers and blind children. She was there for over a year. I was 15 at the time and went to live with my dad.

My letters from her during that time were infrequent at best, the mail service from there spotty and unreliable. But the letters I did get were like stories. She described the places she visited and the people she met. She told me about the children she taught and had grown so fond of. It was hard getting her hands on writing paper and her letters were crammed with her tiny print, looking like a conversation she didn’t want to end. She said she “got her life back in India, and was ready to start again when she arrived home.”

Frances loved to write and receive letters. She wrote letters every day to several people to stay connected with family and friends. Everyone she cared about was a recipient of her letters. In person, she could talk to you for hours, but on the phone she gave you the bum’s rush, her calls short and sweet. Each place she lived in, she’d set up a designated writing spot. When visiting me, inevitably, her writing space was at the kitchen table.

One such visit was in Edmonton where my husband and I lived with our daughters. I was 39, my mom was 71. We were talking in my kitchen, sitting at the table. I made her instant coffee, her favourite. She had been writing letters, her supplies — paper, envelopes, pens, address book, stamps, all laid out in front of her. She was visiting us as she did for years, rotating amongst each of my siblings so everyone got to see her — managing to make each of us feel like we were her favourite.

I was in the thick of things with my own family by this point. We had three teenagers and a baby. Our oldest was causing us a lot of worry. My mom sat listening as I listed off my concerns and crumbled into tears. I don’t know exactly what she said to me that day, but I know it made me feel better. I was thankful to have her there with me at that moment. I remember her in that kitchen, the light of the afternoon, her writing spread out in front of her on the table, our quiet conversation and her gentle support.

Frances was a “people” person. She worked as an occupational therapist for some time and then became an early childhood educator, going to night school to earn her certificate. She both set up and ran daycare centres. She loved children and the energy they gave her. She revelled in making children happy. It energized her and “kept her young.”

At 70, Frances started a new life. She moved to Invermere, B.C., a small mountain town with a population of about 3,000 people. We had a cabin there and brought her for a visit. She fell in love with the town and decided to stay. She volunteered five days a week at the local seniors palliative care centre, feeding dementia patients their meals and keeping them company, reading and singing to them. These were people who were at the end of their lives, locked into wards for their safety, the ones without families who visited. My mother took on this role with energy and optimism, undaunted by the realty of a patient’s situation.

One week the centre invited people to bring their pets to visit the patients as a way of engaging with the community. My mother suggested it might be a good experience for our daughter to bring our dog to share with the patients. My husband went with her. When they got home, my husband, subdued, shared a story with me.

Before then, he said he really had no idea what my mother did at the care centre. But on that day he was in awe of the magnitude of her patience and kindness. He watched as she chatted away, trying to get some food into to an uncommunicative gentleman in a wheelchair.

“Bob, you handsome charmer you,” she coaxed, gently trying to spoon food into his mouth. “Mavis your hair looks beautiful today!” to a fragile woman propped up in a chair. Frances was in her element, devoted, cheerful and enthusiastic, never discouraged by the limits of their illnesses. She often told me her volunteer work gave her purpose and she hated missing even a day if she was sick or her back was sore. She won many awards for her volunteering. Almost everyone in the town had a relative or friend she had cared for in the centre.

She walked everywhere and talked to everyone she met. Wherever I went, people would say to me, “You’re Frances’s daughter?” and share some personal story they had about her. People were far more important to her than things. Every time she moved, which was often, she gave away everything. Her apartments were always sparse, a mix of random items, a collection that would constantly change from one visit to the next. Nothing permanent. On her walls she’d string up strands of Christmas lights for our kids and have stacks of thrift store toys and books for them when they visited. If you gave her a beautiful candle, the next time you visited it was gone, given “to someone who needed it more.” Always paying it forward.

At 81, my mother got terminal cancer. My siblings and I were naively stunned, shocked to think of the possibility that this strong independent woman, such a crucial part of our lives, was soon not going to be here.

When Frances grew sick the library set up a drop-in knitting area for friends to come by and add to a scarf they were making for her as a gift. I was at the library one day when a woman there was learning how to knit so she could add to it.

After she died, I brought potted plants to several of Frances’s friends, wanting to share something from my mom. One showed me a picture of my mom she kept on her fridge, the two of them laughing, their hair swept up by the wind. Another friend invited me to the book club Frances had belonged to. I went and was treated like royalty. A friend who lived across the hall from my mom told me they used to write poems and slip them under each other’s doors for fun. All of them said they missed her.

Frances liked to say she had good bones. Which I believe is true because she never broke any, possibly because she drank large glasses of milk and always carried Tums with her “for the calcium.” I still have her change purse with a few Tums in it. I found it in one of her pockets when sorting through her belongings after she died. It was so personal I couldn’t throw it out. She would be amused that the Tums are still intact, safely tucked into her grey plastic change purse, years after she is gone. And she would be mortified that I have a special stash of her ashes beside me, safe and sound in my night table drawer. “Morbid,” she would say. But I wouldn’t have it any other way.

We all have mothers. But none like Frances.

Tyee readers – we invite you to share a memory of your mother by sending it to [email protected] (you can even include a photo), subject line: Mother memory. We’ll publish some of your submissions in advance of Mother’s Day on Sunday, May 10. Please indicate whether you’d like to include your name or remain anonymous. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: