I don’t think I’ve ever been as aware of my own breathing as I am right now.

Like a lot of people who mostly use their brains to work, I’m in the habit of ignoring my body. Actually, it’s worse than that.

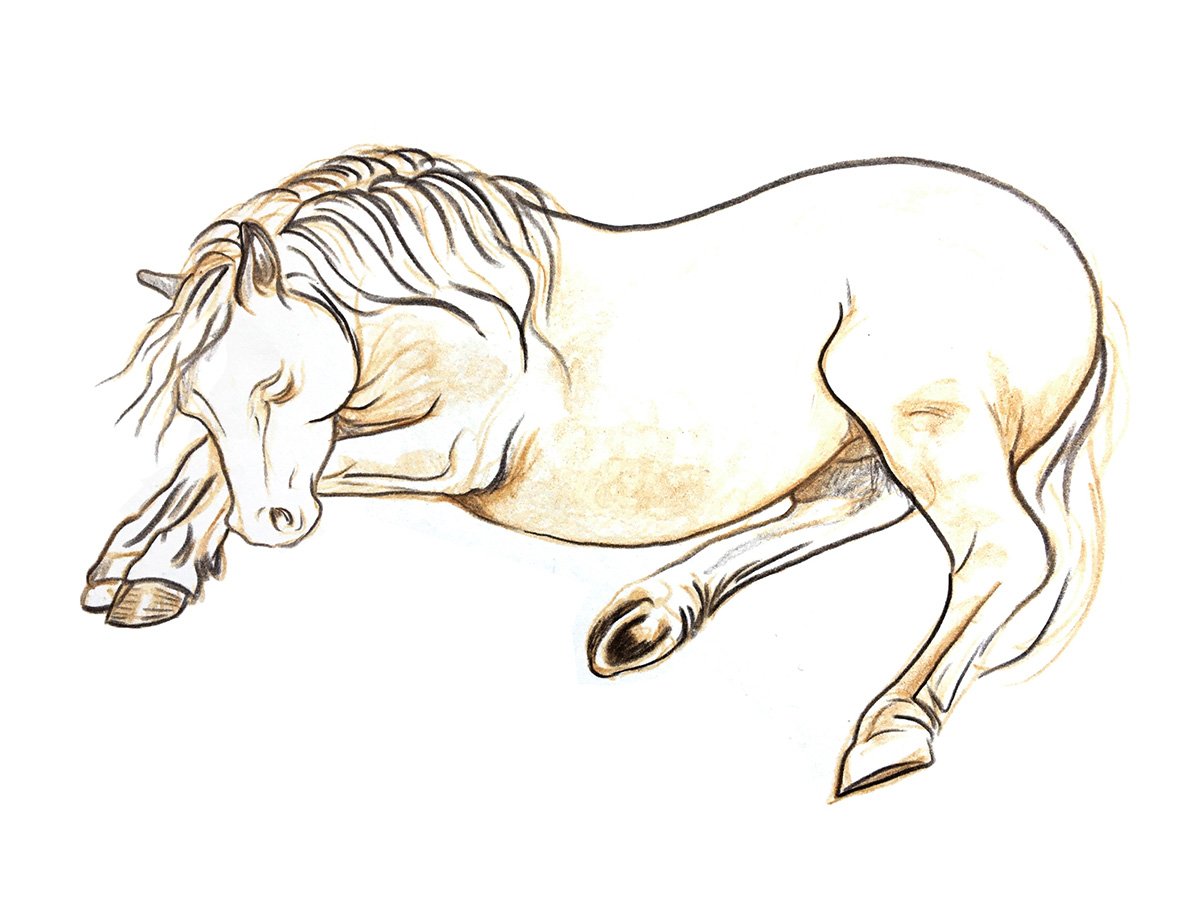

I’m more in the habit of treating it like a sad old workhorse. Every morning I beat it with a panic stick, urge it to work harder, and then put it back in its stall at night, where it cries itself to sleep, eating old oats and bits of hay.

Maybe a slight exaggeration, but not much.

Most humans are trained from an early age to control our bodies — to work when we’re tired, to find extra energy from coffee, to ignore the ache in our shoulders after sitting at a desk for eight hours. Not to pee when we really have to pee.

But a radical reassessment of this relationship has come about. All it took was a global pandemic. Some new conversations are taking place.

“What do you want, body?” I ask.

Sometimes the answers are simple.

“I want to lie down. I want a glass of juice. I want to go outside.”

That makes it sound like a cranky toddler, which isn’t far from the truth.

Other times, the questions are more complicated.

“When will I feel normal again? I want to be less afraid. What does this all mean?”

There was an initial push to be productive during this period of seclusion — start a new fitness regimen, write the great Canadian novel or tidy up one’s messy drawers. But as many thoughtful people have noted, if ever there was a time to sit still, it’s now. In the midst of world-changing events, maybe you and your body can take a moment and simply be together for a spell.

When it’s quiet enough you can hear your heart beating, a sturdy little inboard motor chugging away, the reassuring rhythm moving alongside the rise and fall of the lungs. Even if it looks like you’re doing very little, you’re actually doing something important.

As Rebecca Solnit observed in her recent column in the Guardian: “When you’re recovering from an illness, pregnant or young and undergoing a growth spurt, you’re working all the time, especially when it appears you’re doing nothing. Your body is growing, healing, making, transforming and labouring below the threshold of consciousness. As we struggled to learn the science and statistics of this terrible scourge, our psyches were doing something equivalent. We were adjusting to the profound social and economic changes, studying the lessons disasters teach, equipping ourselves for an unanticipated world.”

Our bodies have been trying to tell us stuff for a while. But now is the first time in a long time that we’re listening.

Here’s what mine is telling me.

Work isn’t everything

Many years ago, there was a made-for-TV movie on CBC about an old blind pit pony that dedicated its life to hauling loads of raw ore from a Nova Scotia coal mine.

Day in and day out, the pony trotted back and forth, pulling its little cart, until one day there was a gas leak in the mine. The entire workforce was evacuated, but the pony, trained by years of obedience, ambles back down into the pit and is blown into pony pieces.

Over the years, the story has become a form of shorthand between my sister and me about the groove worn into our brain that says you’re only clean, pure and valuable when you’re working.

I know others feel this way.

I once had a colleague who kept a stash of meal replacement bars, the kind that astronauts eat, in order to avoid having to leave his desk. I’ve known people who’ve stayed at work into the wee small hours, fighting off the need to sleep. Other folks have burst into hysterical tears in the break room, and one soul even proceeded to lose their mind in the middle of an ordinary workday.

While many people are working flat out at the moment — not just medical professionals, but grocery store workers, cleaners, truckers — one of the more interesting things revealed by COVID-19 is how many jobs aren’t that important. All those Instagram influencers, stock analysts, reality stars and consultants seem like leftovers from a world that has passed on.

For those of us lucky enough to have more time to reflect as the all-consuming busyness stutters and slows, some clarity emerges. Many things that seemed critical and necessary a week back just weren’t. It’s like I’ve stopped drinking the Kool-Aid that tells me I’m only valuable for what I can produce.

All that “getting and spending” that Wordsworth was on about has fallen away, and what has emerged instead is a number of good ideas — a shortened work week, universal income, childcare, flexible hours, working from home. All seem not only obtainable but also reasonable and practical.

It’s not that work isn’t worthwhile and important. It’s just not everything.

You don’t need much

Pared down to the bare minimum, there are only a few things the body needs on a given day — some cleansing, food and drink and a little light exercise. And apparently sourdough bread.

That many people have decided to take up baking is one of the stranger phenomena to emerge from the global pandemic, but it makes sense.

Baking bread fulfills a lot of basic human needs: self-sufficiency, a challenge, and of course comforting carbs. But even if you haven’t managed to start a sourdough yeast from the air, the daily act of cooking has become something to look forward to. It used to be one more thing I didn’t have time to think about, but it’s become a ritual of its own.

It’s a time to try new stuff: you can do so much with a kohlrabi. Some things have worked out well, and others have not. Just don’t ask me about the all-orange meal, please.

The only thing that you can’t give yourself is a proper hug. As Abeer Yusuf wrote in The Tyee, during times of trouble there is an increased need for physical contact. “Touch holds a mantle of sanctity in my life. In times of strife and discomfort, it restores calm and helps ease pain and hurt.”

If you’re lucky enough to be in lockdown with a partner, get all the comfort you can.

Bodies are magical

Along with the usual stuff that crowds into my mind at 3 a.m. when the traffic has stilled and the great dark fills up the corners of my room, there’s a new chorus.

“Do I feel feverish? Is my throat a tiny bit sore? Can I draw a deep breath and hold it for 10 seconds without coughing? Can I still taste, smell, hear, think? And finally, is this it? Do I have it?”

When you get sick, your relationship to your body changes. All of a sudden it’s not a relentless machine that you drive hell bent for leather, but a tired, frightened animal.

We’re learning all kinds of new things about what happens when you get sick with COVID-19, from the minor to the catastrophic. Scientific journals break down the body’s various defence systems, and it’s fascinating and occasionally terrifying to understand how it works or doesn’t when a novel virus arrives.

I’ve learned about the cytokine storm, essentially an overcompensation by the immune system wherein the body attacks itself. The organ systems start to shut down, one by one, like someone walking through an empty house, flicking off the lights, until only the bellows of the lung and the engine of the heart continue for a while, until they turn off as well.

Even viruses themselves are fascinating. Not alive, but not really dead, older than dinosaurs and close companions to human society since the idea was invented. The creation of antibodies is also insanely interesting.

There are practical things you can do the help your body fight off viral invaders. Breathing, rest and vitamin C, along with meditating, walking and dreaming, make life better.

Dreaming mind

An interesting thing to happen recently, not just to me but plenty of others, is the return of the dreaming mind. At night and even during the day, memories and ideas, images and random things resurface, like fish coming up from dark hidden pools.

It’s all in there — the collected moments of one’s life, remembered, even felt all over again. The elastic nature of time has become positively porous, like you could plunge your hand through the membrane that separates past and present and pull these moments wriggling to the surface.

Olga Tokarczuk wrote in the New Yorker about the pace of life slowing. “Images from my childhood keep coming back to me. There was so much more time then, and it was possible to ‘waste’ it and ‘kill’ it, spending hours just staring out the window, observing the ants, or lying under the table and imagining it to be the ark. Reading the encyclopedia.

“Might it not be the case that we have returned to a normal rhythm of life? That it isn’t that the virus is a disruption of the norm, but rather exactly the reverse — that the hectic world before the virus arrived was abnormal?”

It might be something of a leap from the micro of the body to the macro of the planet, but the analogy of not wanting to return to business as usual applies equally to both.

The level of attention currently being levied at the body — when every little twinge makes you freeze in place — can be extended to other aspects of the body politic. What comes out of this moment in history will hopefully be different from what preceded it. I guess we’re about to find out whether humans descend or transcend.

As Arundhati Roy wrote in an extraordinary essay: “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”

But for the moment, although hypochondria is ongoing, I’m incredibly grateful for what bodies are capable of. Not just forestalling sickness, repairing themselves and keeping on, but for feeling joy even in the darkest of times.

So, take your old pit pony self out into the sun. Let it lie down in the grass, close its eyes and fall asleep with the warmth on its back and the breeze gently tugging at its mane. ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: