- Harper's Team: Behind the Scenes in the Conservative Rise to Power

- McGill-Queen's University Press (second revised edition) (2009)

Tom Flanagan is a likable guy. He shows up on TV political panels looking like your favourite uncle with some wicked wisecracks (OK, recommending the assassination of Julian Assange was maybe over the top).

He is also a serious academic at the University of Calgary. As he tells us in the second edition of Harper's Team: Behind the Scenes in the Conservative Rise to Power, he reveals that he is not just a political scientist; he is a political technologist, eager to learn the mechanics of gaining power and -- like any good teacher -- happy to pass his learning on to us.

While Flanagan no longer advises Stephen Harper, he was deeply involved in Harper's progress from right-wing propagandist to prime minister. In the 1980s, Flanagan says, Reform was "just another fringe movement, of which Alberta has seen so many."

But in 1990 he read Reform's "Blue Book" and loved it. It echoed his own views, which were inspired by the Austrian-British right-wing economist Friedrich Hayek. Hayek in those days was very much a fringe item, but was to give some kind of philosophical justification to thousands of conservatives who have never read him (very much like the left-wingers who've never read Marx).

As a full-time professor and part-time dabbler in Reform politics, Flanagan clearly saw Reform as a vehicle for Hayekian changes. His involvement with the young Stephen Harper was tentative at first, but before long they were close associates. They co-authored an important essay: "Our Benign Dictatorship: Can Canada Avoid a Second Century of Liberal Rule?"

Flanagan and Harper learned the ropes of backroom politics as Reform staggered through changes in name, brand and leadership early in the decade. Through it all, Flanagan was clearly taking detailed notes and drawing lessons from the experience.

Fear works

The key lesson: Fear works. Raising money to support Harper's leadership campaign taught him to follow "the time-honoured advice for raising money by direct mail -- make people angry and afraid, and set up an opponent for them to give against."

Even when success was assured, Flanagan wanted to ensure a good turnout of Harper's supporters in the Canadian Alliance leadership race: "We wanted them to be alarmed over the possibility that the Alliance might continue its disintegration... We were happy to let the media wallow in their own disinformation because we wanted our supporters to be motivated to vote."

He also learned "There's nothing so dirty that your opponents won't try to use it against you" -- and that was when Harper's opponents were other members of the Canadian Alliance.

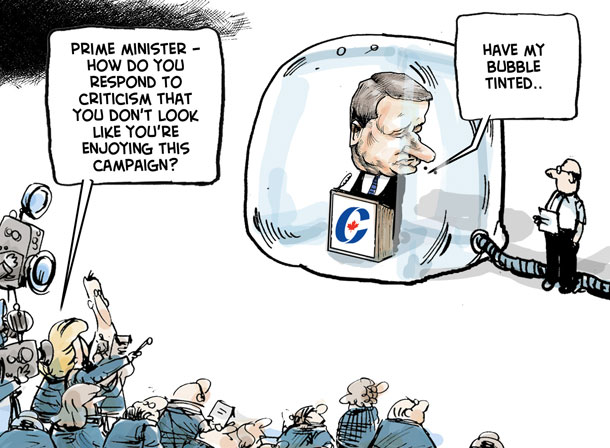

Harper briefly hired an outspoken radio "shock jock" as his press secretary, and quickly learned the importance of message control. Harper, says Flanagan, "wants self-effacing media people around him."

These lessons served Harper well when he engineered the merger of the Alliance and the faltering Progressive Conservatives, and then became the leader of the Conservative Party of Canada. Soon he was planning a campaign against the Martin Liberals in 2004, with an energetic application of attack ads.

That campaign failed, but the Harper team drew more lessons from it -- including the Liberal attack ads that blasted him for supporting Bush's adventure in Iraq. The answer was to increase the use of feel-good Harper ads: "We still feared that hard-hitting negative ads would reinforce the 'scary' image that the Liberals were pinning on Harper." And when Harper talked about forming a majority government, it was a mistake. Flanagan cites an observer who noted that Harper was "scaring voters who might have trusted him with a minority but certainly not with a majority."

'Scaring the shit out of the Dippers'

"You cannot win," says Flanagan about the Liberals, "without a complete arsenal of negative ads to offset the effect of their attacks."

Harper's team also recognized and respected another Liberal tactic, which the Liberals themselves call "scaring the shit out of the Dippers" by posing the Conservatives as the greater evil.

Through this and later campaigns, Harper, Flanagan, and the team learned both to exploit and to survive the tactics of fear. "If chronically fearful moderate or left-wing voters become convinced that Conservatives are a threat to civilization as they think they know it, they are likely to vote for the Liberals rather than the NDP or Greens, because they may think only a Liberal government can keep the Conservatives out of power."

Hence, he argues, "a Conservative government must align itself tactically in Parliament with different parties or segments of parties over different issues" -- that is, form coalitions.

Flanagan's commandments

Flanagan's chapter "Ten Commandments of Conservative Campaigning" sums up what he learned:

1. Unity. The various factions and splinter groups within the CPC coalition have to get along.

2. Moderation. "Canada," says Flanagan, "is not yet a conservative or Conservative country. We can't win if we veer too far to the right of the median voter."

3. Inclusion. This means francophones and minority groups.

4. Incrementalism: "Make progress in small, practical steps."

5. Policy. "Since conservatism is not yet the dominant public philosophy, our policies may sometimes run against conventional wisdom. The onus is on us to help Canadians to understand what they are voting for."

6. Self-discipline. "The media are unforgiving of conservative errors, so we have to exercise strict discipline at all levels."

7. Toughness. "We cannot win by being Boy Scouts."

8. Grassroots politics. "Victories are earned one voter at a time."

9. Technology. "We must continue to be at the forefront in adapting new technologies to politics."

10. Persistence. "We have to correct our errors, learn from experience, and keep pushing ahead."

Judging from Flanagan's account, all these points could have been learned in Harper's first campaigns to lead his fellow Alliance members. Later experience seems to have driven those first lessons home rather than leading on to deeper and more respectful understanding of Canadians and the Canadian political process. As it is, Flanagan's and Harper's view of Canadians is that of a border collie facing 33 million sheep: a mighty challenge, but not one to be spurned.

Flanagan is no longer involved with the Conservatives except as a right-wing pundit. But the 2011 Conservative campaign still looks like another battle of a self-righteous paranoid fringe whose advocates will happily lie rather than admit what their real dreams are: a Canada where Friedrich Hayek would be happy. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Federal Election 2011

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: