When Liberal Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault released Canada’s latest inventory of greenhouse gas emissions Friday, he made it seem a good news story, and that’s how most of the media covered it.

But buried in his press release are some cherry-picked markers and trend lines headed very much in the wrong direction if Canada has any chance of meeting its promise to the planet on emission reduction.

The pledge is this: By 2030, just seven years from now, Canada will have reduced emissions to 40 to 45 per cent below 2005 levels.

Unfortunately, the 2023 National Inventory Report that Guilbeault seemed to celebrate doesn’t offer much hope that Canada will keep that promise.

The report points out that our emissions must drop by 231 million tonnes in order to hold up our end of the 2030 bargain. This is a huge mountain to climb for a country where policy-makers only have reduced emissions by 62 million tonnes over a 16-year period. Can Canada deliver nearly four times that drop in emissions in only seven years?

The recent past says no. “Highly insufficient” — that is Climate Action Tracker’s recent assessment of Canada’s climate change policy record. The federal Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development came to an equally damning conclusion a year earlier.

But those recent assessments belong in the dustbin of history if we take Guilbeault at his word. Canada, he said last week, is “an encouraging picture of progress” that is “focused and relentless” with respect to climate action. Canada, he stated, is “almost a quarter of the way to our 2030 emissions reduction goal.”

The last statement is certainly true. But where does Guilbeault find such reason to cheer? Since 2005, electricity is the poster child for success. Greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation in 2021 were 52 million tonnes, less than half of what they were in 2005 (118 million tonnes).

“The numbers,” said the minister, “speak for themselves.” He’s right, but the numbers other than for electricity paint a picture of negligible or no accomplishment at all.

Gaslighting on oil and gas

Oil and gas makes this case. This sector, now as in 2005, is the country’s largest source of emissions. It’s a sector where you cannot point to even a small reductions in total emissions over this period. Accounting for 28 per cent of Canada’s emissions in 2021 the oil and gas share has grown consistently over time.

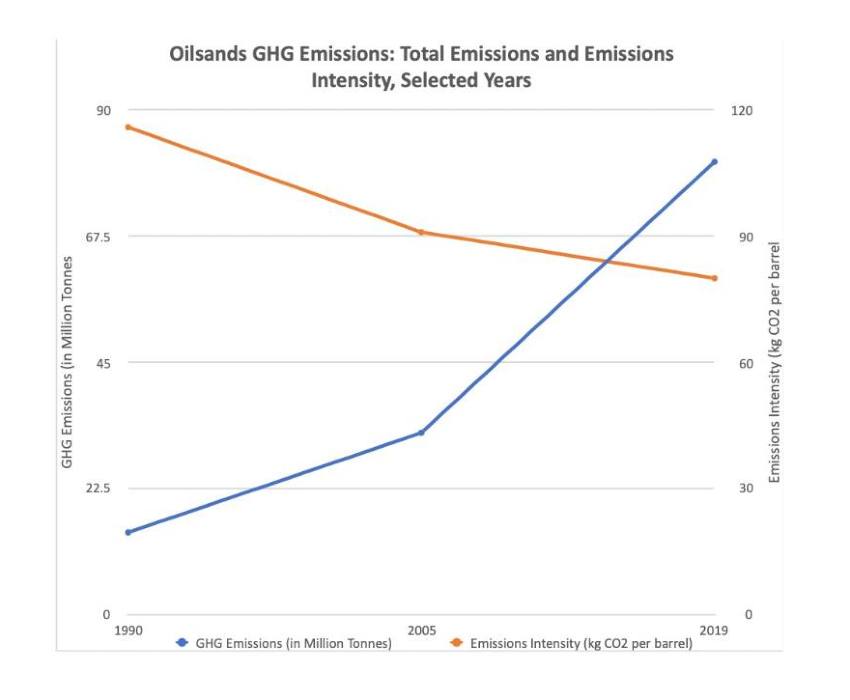

Between 2005 and 2021 petroleum industry emissions have increased 13 per cent, from 168 million tonnes to 189 million tonnes. In 2021, the oilsands recorded their highest greenhouse gas emissions ever. At 85 million tonnes, oilsands emissions were 2.4 times higher than the 35 million tonnes emitted in 2005. We should expect the 2022 emissions data to break this record.

Instead of acknowledging these inconvenient truths, the government soft pedals and is silent about these emission trends and records. The minister’s news release is audacious enough to mention only the oil and gas industry’s “noteworthy achievement” of reducing methane emissions by 15 million tonnes since 2005. The existential threat oil and gas emissions present to Canada’s climate change commitments wasn’t mentioned.

In 2022, oilsands production hit a record level. So too did their profits. Propelled in part by the war in Ukraine, producers recorded extraordinary profits. The Big Four — Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., Cenovus Energy, Imperial Oil and Suncor — amassed $33.8 billion in net earnings. This followed a spectacular 2021 where they generated $14.9 billion in profits.

So far the federal government has not demanded that those producers use their profits to reduce emissions. True to a history of favouritism, the federal government instead has committed only to reduce corporate taxes if companies invest in carbon capture utilization and storage equipment. The 2022 federal budget estimated this refundable investment tax credit will cost taxpayers just over $7 billion by 2030. Enhancements promised in the 2023 budget will increase this total by an estimated $520 million.

Ottawa mentioned capping and cutting oil and gas sector emissions in its emissions reduction plan for 2030. But, counterintuitively, the cap will only be triggered if the demand for petroleum falls first. The cap is not intended “to bring reductions in production that are not driven by declines in global demand.” It’s a measure that sounds reminiscent of the generous cap the Alberta NDP put on oilsands emissions in 2015. That cap allowed the sector to increase emissions by up to nearly 70 per cent from 2014 levels.

The ‘emissions intensity’ red herring

It's also concerning to see the minister embrace “emissions intensity” — the industry’s preferred emissions performance measure — in his statement. Emissions intensity refers to the amount of greenhouse gases emitted per unit of production. It is industry’s favourite metric because it allows the industry to report declining per-barrel emissions in the oilsands. But, if you look instead at what contributes to climate change — the tonnes of greenhouse gases going into the atmosphere — you see a story of emissions generally growing from one year to the next.

Guilbeault tells Canadians that “emissions intensity from the entire economy [is] down by 42 per cent since 1990.” He ignores that total emissions are up considerably.

What he should have stated is that “Canada’s 2021 greenhouse gas emissions were 81 million tonnes or 14 per cent higher than in 1990. This increase comes despite reducing the emissions intensity of the Canadian economy by 42 per cent over that period.”

Judging by the news coverage of the National Inventory Report release, public relations experts won the day. The tremendous gap between today’s emissions levels and where Canada promised to be in 2030 apparently wasn’t particularly newsworthy. The same went for record oilsands emissions.

In November 2021 the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development observed that three decades of climate change policy commitments hadn’t produced any real emissions reductions. Commissioner Jerry DeMarco asked then if Canada was finally prepared to “do its part to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The release and coverage of Canada’s latest National Inventory Report suggests that Canadian governments still are not ready to address seriously the increasing risks a changing climate poses for Canadians and for Earth. No matter how “focused and relentless” is the spin offered by Canada’s minister of climate change. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: