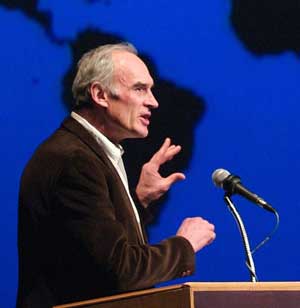

[Editor’s note: In A Short History of Progress, his bestselling 2004 Massey Lecture, Ronald Wright questioned the uncritical embrace of progress by examining the rise and fall of ancient civilizations. The book became a surprise international hit that led to Martin Scorsese's 2011 documentary Surviving Progress, which used his ideas to explore how close our own civilization is to the edge.

Wright, who read archaeology and anthropology at Cambridge, spent several years in South America, and now lives in B.C., is the author of nine books including Stolen Continents, Time Among the Maya, and the dystopic novel A Scientific Romance, in which an archaeologist travels 500 years into the future to survey what remains. On Sept. 26 at 5 p.m., he will give a free public lecture at UBC's Cecil Green Park House as part of the "Utopia/Dystopia: Creating the Worlds We Want" lecture series organized by the Creative Writing Program and Green College. Wright will outline what he calls the 'Progress Traps' that threaten our civilization and the natural world on which it depends, assessing what has changed -- for better and ill -- in the years since he sounded his original warning of what may lie ahead.

Wright recently corresponded with Radovan Zuffa for the Slovakian magazine Profit. Here, excerpted from that interview, is what he had to say...]

On 'Progress Traps'

"What I call 'Progress Traps' are inventions that seem beneficial at first, but turn out to have catastrophic consequences when they reach a certain scale. I give many examples in my book, beginning with simple things like Stone Age hunting (which, as it got more 'successful,' drove big game to extinction) and early irrigation techniques, which in the long run poisoned the farmland. Can we learn from such examples? I have to believe that we can. The main problem is seeing the problem to begin with."

On why 'Archeology is perhaps the best tool we have for looking ahead...'

"In A Short History of Progress, where I wrote that, I was discussing the patterns in human behaviour that have repeated themselves throughout the ages, leading to the rise -- and the fall -- of civilizations. The great ruins that dot the Earth are not simply monuments; they are the gravestones of societies that died, or, to use a modern analogy, the 'black boxes' of airliners that crashed. By understanding these past mistakes, we can hope and try not to repeat them."

On why 'each time history repeats itself, the price goes up'

"That was a graffito I saw somewhere. I take it to mean that as we humans grow in numbers, complexity and impact on the natural world, we expose ourselves to higher and higher risks.

"Several world scientific studies, above all the 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Report, show that we are draining natural wealth and damaging natural systems much faster than they can withstand. In other words, we are living like wastrels who feel rich while they squander a great inheritance. Sooner or later the bank account runs dry. This is the lesson of so many ancient civilizations: when their numbers and consumption grew beyond what their ecology could support, they collapsed in chaos and misery.

"In the past these collapses were local. But now we have one giant civilization feeding on the whole Earth. In the past 100 years, our population has grown by about four times, yet our demands on nature (both consumption and pollution) have grown by at least forty times. I do think more and more people are becoming aware of this, and we're seeing good work towards efficiency and conservation. But which will win: wisdom, or greed? I don't know. But I do know our history is not encouraging here."

On the issues that bother him most

"The widening gap between rich and poor for one, both within nations and between them. Upward concentration of wealth ensures that there can never be enough to go around, especially when both population and consumption keep increasing as if our little world were infinite. Despite some reduction of poverty as a percentage of the human race, the number of people in dire poverty has not fallen -- it is greater than the world's whole population in 1900. That's not progress. Equally worrying is our failure to deal with climate change -- largely because of sabotage by vested interests who have promoted 'doubt' as a reason not to act. This isn't a left/right issue; it's a matter of our civilization's life or death."

On why so little is being done

"Short-term political and economic cycles, when long-term worldwide planning and adoption of 'the precautionary principle' are needed. We are overwhelmed by the pressures and appetites of the present moment, by the endless distractions of the web and the relentless clamour of advertising to buy the latest toys.

"Societies behave much like individuals. They find it very hard to change their behaviour and give up self-destructive habits until circumstances force them to do so. It took two world wars before Europeans decided they could not go on slaughtering one another as they had for thousands of years. One war should have been enough. But in the end real progress was made by the formation of the European Union. Long may it last. Let's not forget the tough lessons of the first half of the 20th century."

On redefining 'success'

"Success is defined by the final outcome. We may say, for example, that we have been 'successful' in avoiding atomic war since 1945. But the great powers still hold enough nuclear weapons to wipe out all higher life on this planet. We will not be truly successful in this area until those weapons are destroyed -- and not replaced by other means of mass destruction."

On whether technology can save us

"People who know much more about science than I do have pointed out that we have all the technology we need to live well and solve our present problems. We do not lack the right tools. What we lack is the political will to apply them, to come to grips with very difficult cultural patterns -- especially as this must be done urgently and fairly on a world basis. On the other hand, powerful new technologies such as bio-engineering, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence will inevitably bring new Progress Traps that we cannot foresee."

On whether he has faith in humanity

"Ask me that in 2050. By then things will either be much better or much worse. If they are worse, then we can only conclude that Nature was unwise to give apes big brains and let them take over the laboratory."

Ronald Wright gives a free public lecture on Sept. 26 at 5 p.m., at UBC's Cecil Green Park House as part of the "Utopia/Dystopia: Creating the Worlds We Want" lecture series organized by the UBC Creative Writing Program. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: