Last spring, when Elida Peña Pomares got the invitation to fight forest fires in Canada, the first question from the team co-ordinator was whether she had a passport.

She didn’t. At 35 she had never been on an airplane. She had never left Costa Rica, where she was born and is raising three children with her husband.

Canada was facing an onslaught of early summer wildfires and needed help, said the message from Pris Carbonell, the administrator at the Lomas Barbudal Biological Reserve, where Peña is a volunteer firefighter. Peña had the skills and experience, Carbonell explained, and if Peña could get her paperwork in order, she could go to Canada.

“My first reaction was that it was very exciting,” Peña told The Tyee in an interview last month outside a bakery in Santa Elena, Costa Rica, a town high up in the mountains. “Very exciting.”

Peña and I had met a couple of days earlier. On a break from my job covering British Columbia politics and public policy for The Tyee, I was wandering around the Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve, a perpetually moist protected area some 1,500 metres above sea level. I’d arrived after two and a half days pushing a badly maintained rented bicycle uphill. A majestic and biologically diverse forest, it sits on the Continental Divide where weather systems off the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea meet.

I’d seen a bluish-grey bird with a black mask and a bright orange beak and legs. Peña was working in the reserve as part of a group of forest rangers and had a copy of The Birds of Costa Rica under her arm. She humoured me by leafing through until we found the black-faced solitaire, an “unobtrusive and not very active” thrush endemic to the highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama.

As the conversation continued, I told her I was Canadian, and she told me a bit about her time fighting fires in Alberta and British Columbia last summer. Listening to how proud Peña was of being part of the team asked to help and the work they’d done, my eyes welled with tears. I’d written a few stories related to the fires, and the memories of the season and the loss of forests, buildings and lives remained raw.

We exchanged contact information and she invited me to spend her day off with her and her 11-year-old son Jefry at another reserve, Curi-Cancha, closer to town.

The morning we met, Peña wore jeans, a Monteverde Cloud Forest baseball cap and a long-sleeved black cotton shirt with a Costa Rican flag on the front and a cartoon firefighter on the back. Jefry, in a grey T-shirt and dark pants, had his hair cut short above his ears and wore a perpetual smile. School was closed in January for the Costa Rican summer holidays and he’d been passing his days hanging out at home and learning to cook.

After a day of watching white-faced capuchin monkeys, bright blue morpho butterflies and a confounding array of hummingbirds — Costa Rica’s 903 species of birds include 52 kinds of hummingbird — I asked Peña if she was interested in giving a more formal interview about her time fighting fires.

People in Canada know we’ve had help from firefighters from other countries, I said, but we don’t know much about what the experience was like for them. I was on holiday, sure, but she had a story to tell that I felt would matter both for Canada and for Costa Rica.

Peña was keen and said that as a volunteer she was free to talk. She spoke for herself, and not for any of the organizations she’s part of.

We sat at a concrete picnic table as poorly muffled traffic rumbled by on the nearby street. Fighting fires is a passion, a love, she told me over her coffee and cheesecake. She’d been a volunteer forest firefighter for six years in San Ramón de Bagaces, in a particularly dry part of her country that includes Lomas Barbudal as well as Palo Verde National Park. She is also a forest ranger working at Monteverde and other protected areas.

Jefry, patiently sipping a fresh fruit juice, looked bemused. None of his friends’ mothers fight fires, he said. It’s something he couldn’t imagine ever doing himself. His father, an agricultural worker, looked after him and his siblings while his mother was away.

The prospect of going to a country like Canada would be super exciting, Peña said.

“Wow, I’m going to represent my country. I'm going to represent the women forest firefighters.” She knew immediately she wanted to be on the mission and was committed to doing her best.

Peña applied herself to getting the passport, and — luckily — it arrived in time for her to join the first wave of international firefighters coming to Canada’s aid from Costa Rica.

Canada was burning, deep into what would become its worst wildfire season on record. British Columbia and Alberta were among the hardest hit, with about 28,000 square kilometres of forests in B.C. and 22,000 square kilometres in Alberta burnt. Almost 200,000 Canadians were subject to evacuation orders.

And in B.C., six members of the firefighting community died during the season: Devyn Gale, Zak Muise, Kenneth Patrick, Jaxon Billyboy, Blain Sonnenberg and Damian Dyson.

People like Peña aren’t the first to be called to fight Canadian wildfires.

Provinces have a basic year-round firefighting service and hire more people in fire season. In B.C., for example, the province typically takes on 1,100 wildfire fighters in fire season.

When more help is needed, provinces can make requests through the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre for resources, including international firefighters. More than 5,700 firefighters from eight countries, provinces and the Canadian Armed Forces joined the fight in Alberta and B.C. last year.

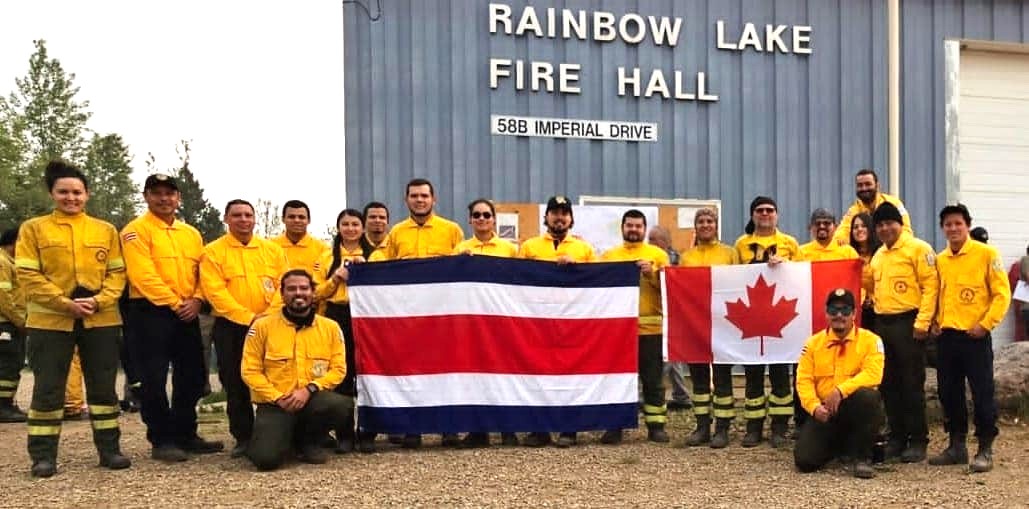

For the Costa Rican firefighters — whose mascot Toño Pizote is a coati, a raccoon-like mammal that serves as a symbol of everyone working together to prevent forest fires — 2023 was the first time Canada had drawn on the country for help.

Peña’s initial deployment was to Alberta, where she arrived on June 14 among a crew of 40 Costa Ricans. They came on a charter flight that was bringing firefighters north from Chile and stopped at the airport outside San José, Costa Rica’s capital, to pick them up.

“It’s my time to do it right, to open doors, to leave them open,” Peña remembered telling herself, adding that she knew Canada as one of the largest countries and a world power. It was a chance to leave Costa Rica and do something big.

“This is your moment,” she thought.

Canada’s population is about eight times Costa Rica’s 5.2 million people, but it is physically 195 times larger. Just the area that burned in Canada last summer is 3.5 times larger than all of Costa Rica.

Despite the Central American country’s much denser population, it has been a leader in protecting wild places. Approximately 28 per cent of Costa Rica is protected land in areas representing the country’s diverse climatic zones — and has been for decades. Canada has a goal of reaching a similar level of protection by 2030, though it is unclear how it will get there.

Among the 40 Costa Ricans on that first deployment, 11 were women. Most, like Peña, were volunteers.

It is normal in Costa Rica for women to serve as firefighters, she said. “In other countries, it’s not very common.”

She was struck by the difference at the airport when her crew met the Chileans, a delegation that didn’t include a single woman.

“It can give a bad impression,” she said, recalling her reaction to the entire Chilean crew being men.

Fighting fires from the heart

With dark eyes and her hair tied back, Peña has a calm presence, and is the sort of person who speaks when she has something to say but doesn’t seem to feel a need for chatter.

Her social media feeds are a mix of firefighting, wildlife and family photos. She most often appears in either a yellow firefighter’s jacket, a green forest ranger uniform or a party dress.

“There are forest firefighters who do it from the heart,” Peña said, adding there are many female firefighters who know what to do, and how to represent their country and their families.

“For me it was nothing more than an opportunity to go and do things well,” she said of the chance to go to Canada.

The plane arrived in Edmonton at night. A woman welcomed them and organized the group for a photo.

“The lady, with tears and everything, told us that she had trust in us, that her cousins had lost everything and she had other relatives who were threatened by the fire,” Peña recalled. “She told us she had confidence in us.”

The Costa Ricans were soon deployed to Rainbow Lake, a community of 500 in northwest Alberta, within a few hundred kilometres of the border with the Northwest Territories, and assigned to fight the Long Lake wildfire west of High Level.

The crew’s first job in the field was to arrange hoses. In Costa Rica they usually roll them in a figure eight or the shape of a snail shell. In Canada, Peña said, they needed to be in a melon shape so that they could be transported by helicopter.

They were to move the heavy hoses six kilometres, work they were told should take all day.

“Thanks to God and the determination of my teammates, and the condition everyone was in, we did it in about two hours,” she said.

Peña believes the Costa Ricans made a good impression on their Canadian colleagues, showing they could work hard and that they were committed. When a group of people has one shared goal, she said, they can do good things together.

Over the month they put out fires using water, manual tools and pumps. They cut trees and branches to create firebreaks. For a sense of the intensity of their work, watch the video below.

Her impression was that while Canadian crews had access to lots of expensive equipment, including many helicopters that Costa Rican firefighters could only dream of, there were few people on the ground, and those who were there were exhausted.

“They didn’t have the human resources,” Peña said. “Equipment, yes, lots and lots, but human teams... I think they lacked human teams.”

During her time in Canada, she saw a warehouse full of equipment — a mountain of pumps, hoses and chainsaws. When equipment is broken in Canada, it is put aside and replaced with something new, she said, adding that she didn’t know if it would be repaired after the season or if it would simply be thrown out.

Alberta Forestry and Parks Ministry press secretary Pam Davidson said in an email, “Equipment is repaired or replaced during the season as well as in the off-season.”

A spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Forests said that damaged equipment is marked in the field, replaced promptly and then repaired if possible when time permits.

“Here in Costa Rica it’s not like that,” Peña said, adding that crews in her country need to get any damaged equipment back in service as soon as possible because they don’t have anything extra. “Here we take very careful care of our hoses because if we break them, it’s something we can’t replace.”

The Costa Ricans had rest days in Peace River, a city 400 kilometres south of Rainbow Lake. They relaxed in a nice hotel and went to Walmart. It was July 1, Canada Day, so there were fireworks to watch.

On July 17, a month after they’d arrived, they went home to Costa Rica. Peña had a couple of days to visit with her children and her parents before gathering in northern Costa Rica for another deployment.

Nine days after she’d arrived home, Peña was back on a plane, this time with a crew of 100 Costa Ricans, many of them women, headed for British Columbia.

They arrived in Prince George, which she calls “Príncipe Jorge,” where they stayed at the University of Northern British Columbia.

She remembers meeting a boy named Owen who was about five and wanted to meet a female firefighter.

“He told me he admired us a lot,” she said. He had confidence in them, he added.

It meant a great deal, she said, adding that she’ll always remember his words and how motivating it was to carry his hope with her.

They drove to Burns Lake, then to a Coastal GasLink pipeline camp called Huckleberry Lodge near Houston. The work was similar to that in Alberta, with the team providing muscle, putting out fires and creating firebreaks.

They had some free time in Terrace and passed through Smithers to get there. They visited the Widzin Kwah Diyik Be Yikh, or Widzin Kwah Canyon House Museum, run by the Witset First Nation in the Bulkley Valley.

There is video from that day of more than a dozen female Costa Rican firefighters in a circle with Indigenous women singing the women’s warrior song, gently bouncing in rhythm with the drums with their palms raised.

Later the Costa Ricans were deployed farther south to fight fires near Kamloops and in the Shuswap region.

On Aug. 27, a month after they’d come to B.C., their return flight to Costa Rica left from the federal military base in Chilliwack.

Peña does not recall receiving any formal thank you from the governments of Alberta, B.C. or Canada, but she said some individuals she met while in Canada generously expressed their gratitude.

Davidson said Alberta Wildfire thanked visiting firefighting crews and gave them Canadian keepsakes to take home. They were also given an opportunity to visit the Edmonton Valley Zoo, West Edmonton Mall and Royal Alberta Museum. There’s also an official thank you, she said, noting “the agencies responsible for exporting firefighters receive a plaque expressing thanks for their significant contribution.”

A spokesperson for B.C. did not respond to a question about how international crews may have been thanked.

Nor has the stipend arrived that they were told was coming from Canada, Peña said, though it’s been more than five months since the firefighters returned home.

Money is always welcome, said Peña, adding she is building a little house in Monteverde and the money would help finish it. But she and most of her colleagues had believed they were volunteering their labour for free and weren’t asking for anything. They were there to do a good thing and were glad for the experience, she said.

A spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Forests said that the province pays the cost of bringing in firefighting personnel and the rate is negotiated by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre. “The home/lending agency is responsible for paying their deployed personnel,” they said. “B.C. is then invoiced by that agency upon completion of their contract.”

Davidson said Alberta’s agreements also include the rate of pay for firefighters as well as some expenses. “Individuals are paid through the contractual agreement,” she said. “Their home agency is responsible for issuing payment for their time in Canada as they are not considered employees of the Government of Alberta under a resource sharing agreement.”

In mid-February Peña wrote to say the Costa Rican firefighters had heard from the managers of their program that money for the stipends had arrived from Canada, but it remained unclear when individuals would receive payments.

Peña said she would love to return to Canada to fight forest fires again, perhaps even joining a Canadian crew if she can learn enough English. A Jan. 25 news release from the B.C. government emphasized efforts to hire locally and said it had already received 1,000 applications from potential wildland firefighters for the 2024 season.

Peña is proud of the work she and her teammates did and said she cherishes the memories. It was the time of her life.

Back in Monteverde, working as a ranger in the cloud forest reserve, Peña knows one day Costa Rica will probably need help too, and that Canada is likely to be one of the countries providing it.

Fire knows no borders and there is only one planet, she said.

“For me, for forest firefighters, fires affect everyone, the whole world.” ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, Alberta, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: